English as a second language and naturalistic learning

This study investigated whether it is possible to provide naturalistic second language acquisition SLA of vocabulary for young learners in a classroom situation without resorting to a classical immersion approach. Participants were 60 first-grade pupils in two Norwegian elementary schools in their first year. The control group followed regular instruction as prescribed by the school curriculum, while the experimental group received increased naturalistic target language input.

This entailed extensive use of English by the teacher during English classes, and also during morning meetings and for simple instructions and classroom management throughout the day. Our hypothesis was that it is possible to facilitate naturalistic acquisition through better quality target language exposure within a normal curriculum. Findings are that 1 early-start second-language L2 programs in school do not in themselves guarantee vocabulary development in the first year, 2 a focus on increased exposure to the L2 can lead to a significant increase in receptive vocabulary comprehension in the course of only 8 months, and 3 even with relatively modest input, learners in such an early-start L2 program can display vocabulary acquisition comparable in some respects to that of younger native children matched on vocabulary size.

The overall conclusion is that naturalistic vocabulary acquisition is in fact possible in a classroom setting. Over the past decades, there has been a trend in many countries of lowering starting ages for learning foreign languages, especially English. One reason is globalization and the role of English as an international lingua franca; another is increased knowledge of the benefits of young starting ages for language acquisition.

Naturalistic acquisition in an early language classroom

However, the relationship between what we know about language acquisition and what goes on in early language classrooms is not straightforward, and it is not obvious that such classrooms make the best possible use of the learners' young age. A number of studies e. Even though the common assumption that children always acquire languages more easily than adults has been contested see e.

This is often attributed to a difference in learning style, as well as maturational constraints related to a sensitive period in language learning Felix, ; Bley-Vroman, ; Newport, Yet little is known about how the factors known to impact on language acquisition interact in the course of development, and what their relative weighting is. Nikolov hypothesizes that a possible explanation for the lack of an early-start advantage in previous studies may be that classroom activities employed in that research were better suited to older learners.

It then follows that what younger learners need above and beyond all else is exposure to the target language—not explicit instruction and formal training. We know that L2 learners are fully capable of acquiring linguistic knowledge without intentional effort or instruction, and that reading and listening alone can lead to acquisition especially in young learners cf. Lightbown, ; Lightbown et al. Amount and quality of input are undoubtedly crucial factors in SLA cf. Hyltenstam, ; Gass, , and there is evidence that sensitivity to frequency is relevant for the acquisition of grammatical items cf.

Larsen-Freeman, ; Goldschneider and DeKeyser, Frequency of language items and volume of language exposure have also been demonstrated to influence vocabulary size, at least in L1 acquisition Hart and Risley, ; Childers and Tomasello, ; Hoff and Naigles, ; Vulchanova et al. As Wode , p. However, it is likely that explicit instruction is less relevant for young learners, and that cognitive maturity may be necessary in order for explicit forms of instruction to make up for impoverished input see e.

There is thus reason to believe that high-input child SLA contexts are the successful ones, and that both intensity and continuation of exposure are decisive factors Burstall, ; Stern, ; Lightbown, ; Abello-Contesse et al. The crucial question is whether acquisition in early-start L2 classrooms can be significantly improved even with only a limited increase in the amount and density of exposure to English.

This can be achieved by giving the language itself a more central place in the English classroom, e. In addition, L2 input can be increased also outside of English class by providing classroom management and simple instructions in English throughout the school day. The present study is, to our knowledge, the first study to use such an approach, and to investigate the effect of such increased input on vocabulary acquisition in the context of English as an L2 in Norway. Norwegian children start learning English systematically in school from age 6. However, the number of teaching hours is low, normally less than one per week Utdanningsdirektoratet, , , and the English input to which students are exposed is thus necessarily limited.

Furthermore, the Norwegian early English classroom typically does not provide very much L2 input, since it largely uses Norwegian as the language of instruction. One reason for this situation may be that English is not an obligatory subject in teacher training in Norway, although most teachers in lower primary school will normally have to teach the subject cf.

Also, the curriculum and teaching materials commonly used in the classroom reflect a teaching style where the target language is the object, but not the medium of instruction. Vocabulary acquisition in an L2 has traditionally been associated with rote learning and memorization of words cf.

However, L2 vocabulary can obviously also be acquired from naturalistic input, as is the case in L1. In fact, vocabulary acquisition may not be subject to age effects.

- The Natural Learning Approach to Second-Language Acquisition.

- 21 Stupidly Simple Ways To Make Fast Cash From Home!: Proven Ways of Thinking Outside of the Box..

- Dracula (Les grands classiques Culture commune) (French Edition).

- Natural Processes in Classroom Second-Language Learning* | Applied Linguistics | Oxford Academic.

- Teaching English?

- The Harcourt Series Set.

While it is the area of language first evident in young children, we all continue to learn new words throughout life. We know that vocabulary is acquired at a fast pace in school see e. On the other hand, vocabulary is an aspect of language for which L1 and L2 acquisition may be assumed to differ. In L1, vocabulary acquisition entails the daunting task of learning concepts and words at once.

The L2 learner, on the other hand, will generally have acquired the concepts already. Many theories have been proposed about bilingual vocabulary acquisition, some involving the L1 as a mediator, while others assume a direct link to the concept. Without engaging in a discussion of the extent to which cross-linguistic lexical variation reflects deeper conceptual differences, we assume that L2 vocabulary acquisition, at least at early stages, and at least when the L1 and the L2 represent similar cultures, does to a large extent entail learning the new labels for familiar concepts see e.

There is thus no reason to believe that neither age nor the presence of an already acquired L1 should have a detrimental effect on vocabulary acquisition, and we should expect that increased exposure to an L2 during the first year of school will lead to naturalistic acquisition and significantly increased vocabulary comprehension. Specifically, it is likely that input alone is particularly beneficial for vocabulary acquisition in young L2 learners.

Shintani explicitly investigated whether input-only instruction may be as effective as production-based instruction for 6—8-year old Japanese learners of English, hypothesizing that mechanisms such as fast mapping are still available at this age. The conclusions of her study are indeed that in this age group, the effect of input-based instruction on vocabulary acquisition is as good as, or better than, that of production-based instruction. The present study investigates whether employing a bilingual approach to an otherwise normal Norwegian first-grade English classroom will lead to improved acquisition over 1 year, compared to a standard, i.

The research questions are whether children in each of the classes improve significantly in vocabulary acquisition over their first year of school, and whether there is a measurable difference in the two groups' vocabulary comprehension at the end of the first grade. Two different schools were recruited for the experiment. In one school, teachers were told to do nothing out of the ordinary, and to teach English to their first-graders the way they would normally do, with the L1 as the main medium of instruction.

In the other school, teachers agreed to use English more extensively with the children in and outside of English class, such as for morning meetings, simple instructions during the day, and reading aloud. However, they were not instructed to avoid the use of the L1; this school's approach to English teaching can thus be said to be bilingually-based.

The two schools were both standard state schools, situated in similar suburban areas in one of Norway's largest towns. The areas from which the schools recruit their pupils are socioeconomically comparable; they are both relatively affluent, with mean incomes slightly above the national average. The ethnic makeup of the two neighborhoods is also comparable, with a low percentage of families with immigrant backgrounds. On the national tests of English for 5th grade in the two schools scored similarly at or in the case of the native language-based classroom's school a little above the average.

Thus, there is every reason to believe that these two schools are comparable in terms of student population and quality of teaching, and that they are representative of Norwegian state schools.

- You must create an account to continue watching.

- Account Options.

- Natural approach!

- Spoken For: Embracing Who You Are and Whose You Are.

In addition, a parent questionnaire asked for background information about the children concerning factors such as foreign travel, English-speaking friends and relatives, and input received through media. None of the participants included in the study had extended stays beyond normal vacations abroad, and none had close English-speaking family or other special circumstances which might make their English competence atypical for a Norwegian 6-year-old.

Although the parental reports were relatively crude, information was quantified by counting weeks spent outside of Scandinavia and hours per week with English exposure from games and media prior to starting school. Mean, minimum and maximum values and standard deviations SD for weeks spent outside of Scandinavia and hours of exposure from media, games and music prior to starting school in the bilingually-based and the native language-based groups. It thus seems safe to assume that these children's English exposure outside of school was similar.

Children in the two groups were also similar on a number of factors that may potentially influence English acquisition, which will be more closely described in the test materials section. In each school, three different classes and class teachers participated in the project. In the bilingually-based school, one teacher had the main responsibility for English classes in all groups. In this school, groups were often organized across classes for various subjects, and this teacher was a natural choice for English classes since she was a native speaker of English.

However, all class teachers participated in providing input throughout the school day. In each school, one teacher was responsible for recording information on time spent on English, and about activities and materials used, and to report to the researcher. These reports were frequent and relatively informal during the two periods of test sessions in September and May.

In the middle of the spring term, both teachers formally reported on the same three questions time, activities, and materials in emails to the researcher. Information from both schools indicated that they consistently followed the pattern described below throughout the test period. The native language-based condition school reported formally spending 30 min a week on English class.

They also reported spending a few minutes in morning meetings every day talking about the weather and the names of the days in English, but these meetings were otherwise conducted entirely in Norwegian. The time spent on English in this group was thus of around 45 min per week, which is representative of the average that normal Norwegian schools spend in the first grade. Also representative is the fact that communication during this time took place mainly in Norwegian.

Activities in this group included the use of the workbook Junior Scoop 1—2 Bruskeland and Ranke, which is intended for use in first grade, and which contains simple activities, including routine instructions, rhymes and songs. Furthermore, teachers reported a number of other English songs used in class. The bilingually-based group spent about 30—40 min per week on English class. While this school also uses the Scoop series of work- and textbooks, it was not used in this group of children.

The teachers instead used various other materials, including simple stories and books, which the teacher read aloud, often with illustrations. Teachers would also spend time talking about pictures or objects. Furthermore, this group spent more time speaking English during morning meeting time; the teacher estimated about 5—10 min per day. While the native language-based group's morning meetings were conducted in Norwegian, with only routine discussion of words for the weather and the days of the week in English, morning meetings in the bilingually-based group were more or less conducted in English on the part of the teacher, while the pupils were free to answer in either language as they wished.

It is important to point out, then, that the change in the English classroom of the bilingually-based group did not consist of more formal instruction or an increase in teaching hours for English. Time spent on English was a little higher than is normal in Norwegian schools, but with an average of around 70 min per week including morning meetings, it still is a small proportion of the total time spent at school.

Furthermore, there was no focus on pupils' production, even though increased L2 production may have been a natural consequence of the increased input. In other words, the change in this school consisted solely of an increased focus on providing target language exposure in a natural context. All parents of students in the relevant first grades were contacted in writing and asked for written consent for their child to participate.

In the bilingually-based group, the total number of volunteers was From the remaining 49 children, 31 were randomly selected for the project by the researcher. The final test group consisted of 17 boys and 14 girls, all monolingual speakers of Norwegian with no known diagnosis which might influence acquisition. In the native-language based group there were 35 volunteers. Three were excluded because of bilingualism, and one because of hearing problems. Two children participated in the pre-test only; one because he was not available during the post-test, the other because he did not want to participate in it.

The final test group consisted of 15 boys and 14 girls, all monolingual and with no known diagnosis which may have had consequences for the study. Mean, minimum and maximum values and standard deviations SD for age, vocabulary, verbal and non-verbal intelligence and memory scores raw in the bilingually-based and the native language-based groups.

This test measures vocabulary comprehension by means of pictures; the subject hears a word and selects the corresponding picture from a set of four options. This means that issues related to literacy can be avoided, and no L2 production is necessary on the part of the participant. Both these criteria made the test particularly well suited to these young learners, whose level both of literacy and of English was too low, especially in the pre-test, for more comprehensive tests to yield reliable results.

Pre-testing took place within the first 6 weeks of the children's 1st school year. There were no significant differences between the groups on either of these tests. Post-testing took place during the last 6 weeks of the school year. During this test session, in addition to the post-test of English vocabulary comprehension, visio-spatial working memory was tested using a memory game where the child memorized sets of picture cards which were then turned face down, and was asked to find the pairs in as few attempts as possible.

These particular control measures, including L1 vocabulary, were chosen firstly to control for group differences on the outset, and secondly to provide measures that are believed to correlate with L2 acquisition. There are consistent findings in research suggesting that L2 language competence correlates highly with working memory, non-verbal intelligence, and, most importantly, L1 competence and skills Colledge et al. Mann-Whitney U , Z, and p for between-groups comparison of vocabulary, verbal and non-verbal intelligence and memory in the bilingually-based and the native language-based groups.

Each test session was conducted at the child's school, during school hours or in the after-school program. Testing took place in a quiet room, with only the child, the researcher, and sometimes an assistant present. Each test session lasted for approximately 1 h. Most children were able to complete test sessions without signs of fatigue; if they did show signs of losing concentration, they were given a short break. Average time between pre- and post-testing was eight months in both groups. Because the sample is relatively small native language-based: Results from the pre-test reveal that the children in general knew very little English when starting school.

The mean raw score of the native language-based group was The mean raw score in the bilingually-based group was In short, these Norwegian children demonstrated English comprehension comparable to very young English-speaking children. Competence was very similar between the two groups, even though the bilingually-based group did score slightly higher. According to the manual Dunn and Dunn, b , p.

The difference between an average score of For the repeated-measures test, the Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used. The effect size for the bilingually-based group was 0. Successful L2 acquisition does not necessarily equal near-nativeness, but comparison to L1 acquisition may nevertheless be useful for purposes of illustration.

Thus, the native language-based group's non-significant mean increase in receptive vocabulary translates into an equivalent of only 3 months' development in native English children, from age 2;4 to age 2;7. Age equivalents of pre- and post-test vocabulary scores raw in the bilingually-based and the native language-based groups. The mean age equivalent of the bilingually-based group, however, has increased by 10 months in the course of an average time span of 8 months.

This means that these L2 learners have, on average, been acquiring new words at a slightly faster rate than the average for children at the same stage of language development, who are acquiring English as their L1. The main difference is that, while this development on average takes place between ages 2;5 and 3;3 in English-speaking children, it took place between mean ages 6;1 and 6;9 in these L2 learners. This is quite an astonishing development, considering that the input to which these children have been exposed is still very limited compared to that of children acquiring their native language.

The results thus clearly indicate that there is no inherent problem in the early-start foreign language classroom per se preventing it from being successful, at least not with respect to vocabulary development. It is worth looking at group differences for cognates and non-cognates separately, since there may be differences in how the two categories are acquired.

Words that sound similar in the two languages cognates are given in bold. Percentages of correct answers and Mann-Whitney U, Z, and p for between-groups comparisons of number of correct answers for cognate and non-cognate words in the bilingually-based and the native language-based groups. The words which are successfully identified by virtually all children in both groups are cat , apple , balloon , and hand , all of which are phonologically similar to their Norwegian counterparts katt, eple, ballong , and hand.

However, the bilingually-based group scores slightly higher also on these words; for apple and hand , the difference is significant. Furthermore, the words tree and drinking are recognized by virtually all the children in the bilingually-based group, and the difference between the two groups here is significant. These words also sound relatively similar to their Norwegian counterparts tre and drikke. However, the children in the bilingually-based group outperform their native language-based group peers also on non-cognates. The percentage of children who correctly identify the words airplane and bird , whose Norwegian equivalents are fly and fugl respectively, is slightly higher in the bilingually-based group than in the native language-based group, although the difference is not significant, while the differences for the words money Norwegian penger and umbrella Norwegian paraply are significant, and the word table Norwegian bord is the one with by far the biggest difference in scores.

Naturalistic acquisition in an early language classroom

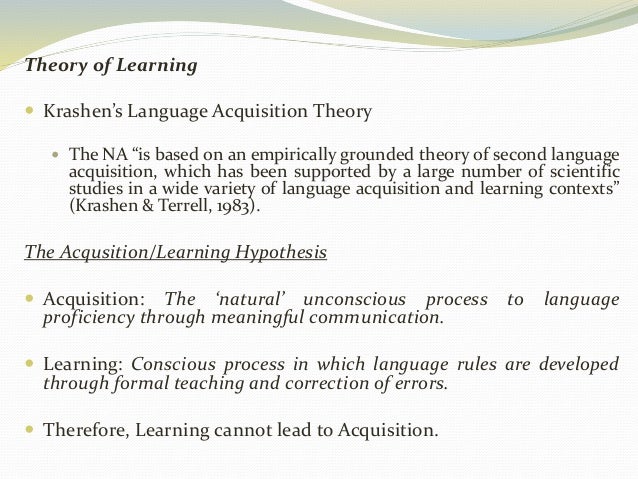

He divides these activities into four main areas: The natural approach was originally created in by Terrell, a Spanish teacher in California , who wished to develop a style of teaching based on the findings of naturalistic studies of second-language acquisition. Terrell and Krashen published the results of their collaboration in the book The Natural Approach. The natural approach was strikingly different from the mainstream approach in the United States in the s and early s, the audio-lingual method.

While the audio-lingual method prized drilling and error correction, these things disappeared almost entirely from the natural approach. The natural approach shares many features with the direct method itself also known as the "natural method" , which was formulated around and was also a reaction to grammar-translation.

The aim of the natural approach is to develop communicative skills , [6] and it is primarily intended to be used with beginning learners.

Navigation menu

These principles result in classrooms where the teacher emphasizes interesting, comprehensible input and low-anxiety situations. Terrell sees learners going through three stages in their acquisition of speech: His aim is to make the vocabulary stick in students' long term memory, a process which he calls binding. According to Terrell, students' speech will only emerge after enough language has been bound through communicative input.

In this stage, students answer simple questions, use single words and set phrases, and fill in simple charts in the foreign language. Although Terrell originally created the natural approach without relying on a particular theoretical model, his subsequent collaboration with Krashen has meant that the method is often seen as an application to language teaching of Krashen's monitor model. Despite its basis in Krashen's theory, the natural approach does not adhere to the theory strictly.

In particular, Terrell perceives a greater role for the conscious learning of grammar than Krashen. Krashen's monitor hypothesis contends that conscious learning has no effect on learners' ability to generate new language, whereas Terrell believes that some conscious learning of grammar rules can be beneficial. Terrell outlines four categories of classroom activities that can facilitate language acquisition as opposed to language learning:. The natural approach enjoyed much popularity with language teachers, particularly with Spanish teachers in the United States.

First, he says that the method was simple to understand, despite the complex nature of the research involved. Second, it was also compatible with the knowledge about second-language acquisition at the time. Third, Krashen stressed that teachers should be free to try the method, and that it could go alongside their existing classroom practices.