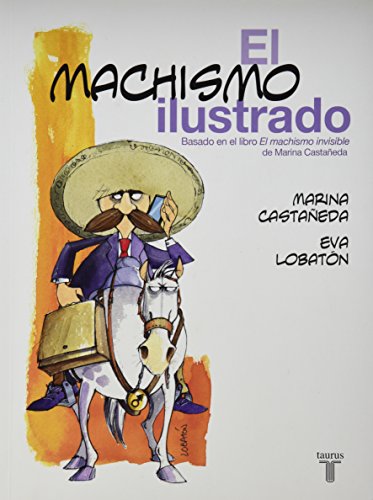

Antología del machismo ilustrado (Spanish Edition)

In these regions there reigns heresy. And is it not rash, to take up in our country as good and decent, what, in fact, a loose conscience has fostered in such countries? Having underlined the point that hardly anyone believed the cortejo to be a custom linked to an old gallant Spanish tradition, it would be worthwhile to take a brief glance at its closest intermediary, the chichisveo, before entering into the broader topic. What made the life of married women and widows so pleasant, first in Genoa, then in Venice, and finally all over Italy, seems to have stemmed from the fact that Genoese men had to travel constantly because of their businesses.

The husbands welcomed with a sigh of relief the institution of the chichisveo, that is, of an attentive escort to a bored wife. It was this acceptance on the husband's part that spread and perfected the custom among the Genoese to the point that often the choice of the chichisveo was a family matter. The name of the gentleman designated to fulfill this charge was agreed upon by husband and wife, and was included in the marriage papers.

Giuseppe Baretti suspected that half of these relationships might have been chaste, and the other half not. Nevertheless, the proper thing to do was to consider the doubtful ones platonic, and to behave as if indeed they were. Jealous husbands cut a ridiculous figure. He had to show up at his lady's house every day at nine on the dot, to serve her chocolate or coffee in bed, making sure to open the windows and to wake her gently.

If the lady, for instance, asked him to fetch her a pin, to demurely close her nightgown around the neck, he had to look for it around the room, and feign he did not see the one she had at her hand's reach. The chichisveo did not have to leave the room if the chambermaid was not present; on the contrary, he was to help the lady to get up. He was to assist her at her dresser, standing behind her like a servant, to be ready to hand her all of her cosmetics and to give her an opinion on the effect they produced on her face.

After the dressing up, he would. He would rush to the door to offer the lady holy water from his fingers. In the afternoon, he would accompany her to the theater and sit by her. In the same text that described in great detail the guidelines for the Spanish cortejo there follows a cynical but revealing comment uttered by a husband complying with the fashion:. We Genoese husbands are too busy, while our wives are not busy enough, to be satisfied to get along unaccompanied.

They need a gallant, a dog, or a monkey. The Genoese gentleman who solved the problem in such a contemptuous way had nonetheless put his finger on the right spot. It was a matter of idleness. The ladies all over Europe were bored. They were not any more bored than they had been in other eras, but—and this is a feature of the eighteenth century—they started to become aware of it. They began to feel restless and to rebel; they had to fill their idle hours somehow. I fully realize [noted an eighteenth-century author] that woman, fated, according to our customs, to keep to her home the greatest part of the day, has to have somebody to talk to in the moments when she is not taken up by her domestic duties.

This recognition, unusual in Spain, had already occurred in the rest of Europe, where along with the tendency to disregard spiritual values while stressing the worldly, women were encouraged to enjoy life freely. They had a function in that hedonistic society; they were its indispensable adornment, and they had to learn how to perform the new role, discarding the old coyness and reserve. To express it with a phrase of the Goncourt brothers, they had the obligation to "introduce in society the image of pleasure, offer it and give it to the whole world. A gentleman finds you pretty.

Don't blush, open your eyes wide. Here, women never blush unless they have just scrubbed their faces. One should analyze the motivation underlying the zest with which Spanish women took to these new styles because, I believe, it was this enthusiastic reception which gave the cortejo its peculiar traits, which were far less opposed and discussed in other countries than in Spain. No one will be surprised to hear that Spanish women had been starving for blameless amusement.

The guiding models from literature and sermons which they had been constantly asked to follow were of an exasperating monotony, and did not offer any alternatives but boredom or sin. For centuries, maidens and married women had been persistently indoctrinated to curb their inclinations, and to reduce them to a minimal expression. The maidens had to do so in order not to lose the chance to marry; only by living in seclusion did one gain the good name that was all-essential for candidacy to marriage.

Once married, no one would have dared to argue that anything more was to be desired, and one's tastes automatically changed into the husband's. Needless to say, many girls. Maidens think they will be free to go here and there, when they leave the house of their parents and enter their husband's. Why don't they look at their friend, married to a jealous and harsh man that never spoke to her kindly, that never let her go out of the house without grumbling, not even to mass, not even clad in a plain cloth dress and wrapped in a cape as a servant?

Let neither the maiden nor the widow [he concludes] aim at freedom. Throughout the Golden Age period, it seems as if married women did not exist. In the plays of the time, hardly any references were made to the problems of matrimony once contracted; on the contrary, much emphasis was placed on the preparation for it and the homages men offered a lady to gain her favor. Spanish women, once bedazzled by the flames of courtship, passed from being queens to whom one dedicated verse and duels, to recluses in a world which no stranger penetrated.

They became unassuming, virtuous matrons who had ahead of them—given the early age at which they contracted matrimony—more than half of their lives to ruminate in solitude the memories of those compliments to their beauty, and to prove the fickleness of those homages. While married women in France had started to preside over literary salons, Spanish husbands took pains, each within his means, to furnish a cushioned and silent precinct worthy of his spouse.

Inside this carefully adorned room was a place where she might be seated: The estrado was raised by means of a platform of cork or wood and separated from the rest of the room by a delicate railing. It was furnished with cushions, stools, pillows and low chairs; to introduce a gentleman to this precinct was an exceptional proof of trust. The estrado did not become altogether obsolete in the eighteenth century; it persisted like a bastion of the separation of the sexes.

The latter take their seats in a particular chamber, and etiquette requires they should remain alone until all the company be assembled, or at least until the men stand up. The lady of the house waits for them under a canopy in a place set apart in the hall. This special area, which in the past was called the estrado and over which is hung an image of the Virgin, is still used. The appearance of the refresco at length enlivens every countenance and infuses joy into every heart; conversation becomes lively as the sexes mix.

Throughout the Enlightenment, the estrado was mentioned nostalgically by many authors who objected to the dawning freedom women were gaining for themselves. Happy times were those in Spain when modesty had ruled fairly and prudently in the estrado. One would observe beauty at a distance, and from a distance reserve would control the dangerous hosts of the emotions.

But long before this system of reclusion and isolation began to crumble, some moralists—with the fathers and husbands, joint custodians of feminine behavior—had an uneasy suspicion that those secluded women were bored, and that this boredom, incubating and souring day after day, might lead to some unforeseen evil.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries abounded in diatribes against women's idleness and against the evil thoughts that might arise in their minds. These moralists did not understand, or did not want to understand, that all well-intentioned considerations of women's idleness and passivity clashed with the imposition of women's reclusion.

Foremost prose writer and poet. His life was overshadowed by a long and intricate investigation during the Inquisition; among other reasons, he was investigated for his defense of writings on the Bible and translations of passages from it in Castilian. Married Woman , he was fully aware of women's discouragement and of the support they needed to fulfill their unrewarding task. As women are prone to be pusillanimous and little inclined to brave things, they are to be encouraged; when their husbands treat them badly and hold them in no esteem, they become downhearted and crestfallen.

This is precisely what he wanted to avoid by all means: The undefined wishes she might have harbored in her youth and kept latent, her frustrated yearnings for domain and influence, were preferably channeled towards the education of the children, especially—and this is essential—of the daughters. In this way, married women collaborated with men in the formation of new obedient and submissive women, feeding a cycle in which the patterns of behavior were transmitted from one generation to the next with the aridity and lack of vitality characteristic of norms inculcated without any inspired touch, albeit with the efficiency of experience of a well-trodden and inevitable path.

Later on we shall see the persistence of this ideal woman, fashioner of daughters in her image. It was well known that women, since time immemorial, liked to vie with each other in the acquisition of new clothes:. When a woman [says a writer of the sixteenth century] sees her neighbor with something new on, it gets into her head that she is worthier of it than her neighbor. They make it a case of honor. In Spanish classical literature, it is common to find the type of the wedded woman who falls for money, from having been far too harshly curbed in her most basic whims.

Seducers knew of this all too well and took advantage of it by offering presents through procurers. The husband who does not give his wife enough to buy a gown, or a mantle, or a shift, or a pair of slippers, or a headdress, or a cape, nor gives her enough to clothe the children, or to pay the servants, and on the other hand sees her supplied with all these things, improved in her appearance and respected, had better think she has earned it by wandering about, rather than by weaving. Alas, how many women are bad, not because they want to be bad, but rather because their husbands don't give them what they need.

Here was the core of the question: There were many women, of course, who preferred to overlook those canons, but society never let them forget that they had swerved from the straight way. Only the character of each woman determined how she would face up, cheerfully or with regret, to the consequences of disobeying the sermons that linked luxury with dishonesty.

La Bicyclette Bleue Tome 8 Pdf

Luxury and ostentation were attributes of sin. In this respect, it is interesting to point out the clear-cut difference that was accepted until the eighteenth century as existing between ladies and courtesans: To avoid all possible confusion laws were passed like the ones of , to the effect that:.

That does not mean they succeeded in banishing luxury through such laws, promulgated throughout the years by successive monarchs. What they did achieve was to discredit luxury as immoral. Though officially a royal preacher, chronicler at the court of Charles V, and author of moralizing sermons, he wrote for the sheer pleasure of inventing stories and situations, which he wittily disguised with sham erudition.

Luxury was coveted secretly, avoiding any show of it, because luxury and money were immoderate desires, typical of courtesans who, though they enticed men with their bizarre clothes, also paid for it with indelible disgrace. In regard to this, a remarkable subversion of values took place throughout the eighteenth century, to reach its peak during the reign of Charles IV.

The right to enjoy a luxurious life was being achieved and recognized gradually in Spain, although still lagging in comparison to the rest of Europe. Almost all foreigners coming to Madrid complained of it being an inhospitable, spread-out town, lacking in comforts, in public services, and far too sober in its mode of life. The aristocrats were thought of, in general, as close-fisted and provincial in their manners as well as in their homes and attire:. The simplicity of their manner, their little taste for ostentation and repugnance to ruinous arts which, in other kingdoms, are found so seducing conspire to preserve the estates of the Spanish nobility.

Another foreign author informed us that the noblemen's life was meager, their servants clumsy and uncouth, and the rooms in their mansions, with the exception of the hallway, stairway and the reception room, neglected and tastelessly furnished. Ambassadors from abroad pointed to another way of life, spurring Spanish noblemen to get out of that rut.

If, instead of taking for comparison life abroad, one takes the life led a century before in Spain, the description is quite different. According to Spaniards themselves, life, since the beginning of the century, had altered considerably; there had been a tendency toward spending and magnificence. Above all, women began to know how to dress up and entertain in their homes, how to behave out of them, and how to supervise the renovation of their rooms.

The elegance with which parties were given was unheard of before this time. This salon was attended by the marquis of Valdeflores, the dukes of Bejar, Medinasidonia, and Arcos, and other noblemen and literati of the time. The famous Academy of Good Taste—which lasted from January to September —flourished there, when lady Josefa remarried and became the Countess of Sarria.

The ecstatic description, made by a contemporary, of the rooms of that mansion makes one think of the difference in standards between the Spanish noblemen—unaccustomed to luxuries—and the travelers from beyond the Pyrenees, when they dealt with the same topic. I was astonished at the spacious and regal gallery, with gilt railings giving onto the gardens. Its high walls were hung with enchanting paintings; some with mythological subjects, others symbolizing literary genres; at intervals, statues of the Muses with their respective symbols; in front, Apollo, crowned by the sun's rays and plucking the lyre.

From this hall one could make out an equally majestic salon hosting the library, which included the complete works of all Spanish authors, the most valuable of them being the manuscripts and the unpublished works. There are many more testimonials—especially among women— of the widespread desire to shake off rusticity and inhibitions and lead a life of luxury. The new philosophical trends, with their stress on worldly happiness, had, in part, pushed aside mystical preoccupations; consequently, women not only aspired to gracious living, exhibiting at the same time their inclination toward it, but also felt they were gaining prestige by such a display.

One can detect an almost resentful attitude toward austerity, a definite reaction against the idea of the thrifty wife. A contemporary remarked that the majority of women came to consider economy with distaste, and that as soon as this word was mentioned. How many among the many that reject thrifriness do squander their estate, do finish off a noble house, disregarding the pains it cost to establish it! There are as many of them as consider it tedious not only to economize, but even to hear the word economy.

Oddly, this tendency toward lavish spending in private homes was opposed by the policies of the enlightened government, whose monarchs and ministers praised economy repeatedly, so loathsome to women. The innovations of the Enlightenment were based on intensifying national industry and commerce to heal the economy of the country; that is to say, they needed private investments. This is one of the main contradictions of the period. If, with their Christian mentality, the Spanish "enlightened despots" condemned superfluous spending on luxury items as immoral, they could not overlook the fact that the money immobilized for so long in private coffers, by being splurged, was contributing very efficiently to the development of national enterprises.

This is the way a contemporary sized it up:. If men were content with the bare necessities there would be hardly any trade; consequently the national income would diminish to the point where there would not be sufficient money for the defense of the country and other government enterprises. Let us assume that everybody stopped using tobacco, one of the lesser necessities. He added that vanity, fostered by luxury, should be considered a minor evil to avoid a major one:. Likewise, the Basque Economic Society, in its amendment of the previous year's report, in which luxury had been praised as a sign of progress in , made its point thus:.

If one interprets 'luxury' in its absolute terms—unrestrained squandering of one's means—it is obvious that one cannot speak in favor of it, lest one be considered rash and scandalous. Evidently moral reasoning was in conflict with monetary and economic matters. Women were taking advantage of the truce—in which the good and bad sides of spending were elucidated—by laying the foundations of the consumer era. They were the ones who contributed the most to the creation of new demands and needs, implanting them in society by eagerly receiving the fashions from abroad. Hardly have the marriage papers been signed.

Ornate clothes for the upstairs servants, and gold and silver trimmed liveries for men who would be better employed in the fields. Carriages in the French style. This text points out two circumstances that changed family life in the eighteenth century: These walks, needless to say, gave the opportunity to show off, and what mattered was the good appearance of clothes and carriages, rather than their quality.

The custom of promenading in an open carriage was quite widespread in the second half of the century, and had passed from being an exclusive habit of the nobility to a device by which the bourgeoisie could aspire to prestige as well. The competitive character of these parades was obvious, as revealed in the description made by an English traveler. When they rise from the siesta , they get into their carriages to parade up and down the prado [sic.

As they move slowly on in one direction, they look into the coaches which are returning in the other, and bow to their acquaintances every time they pass. On some high days, I have counted four hundred coaches, and on such occasions it requires more than two hours to proceed one mile. After the walk, it was customary to invite one's friends home for tertulia , called sarao if enlivened by a dance. During the whole of the seventeenth century—as has already been pointed out in reference to the estrado—the home and the family were the sanctum sanctorum.

Family was considered somewhat a spiritual good, not belonging to this world, and if it were to be had here, it had to be secluded and defended. To open one's home to visitors, to summon up a warm atmosphere for people who did not belong to the family, was an important step in the life of society. New friendships gave prestige to those who knew how to cultivate them; so it was not only a matter of wanting to meet more people, but rather of exhibiting in front of them one's own way of life.

Even so, gaining ground in this direction was a slow process for one basic reason: Spanish ladies, products of a secular rigidity, did not know how to receive graciously; it took them a long time to grasp those ways with ease. They entered and saw in the estrado more than a dozen women, each more extravagant and dolled up than the other.

Don Jacinto noticed that those women did not sit anywhere for long, as they kept changing places and looking for each other; hand in hand, they were going to the balcony chattering incessantly. During the first half of the century, the ladies did not succeed, as a rule, in ridding themselves of the stiffness and gravity habitual to them. Consequently, the gatherings they frequented—where they did nothing but fan themselves in a corner, serious and pathetic, while the men, in another, played cards—were an obvious residue of the estrado.

One entertained on set days, and to make the gathering more pleasant, refreshments, sweets, and hot chocolate were served. The company are first presented with tall glasses of water in which are dissolved little spongy sugar loaves called Azucar esponjado or rosado; these are followed by chocolate, the favorite refreshment of Spaniards who take it twice a day, as it is considered nourishing or at least digestible; it is not even denied to moribunds. After the chocolate came all sorts of confectionery.

These gatherings—often made merrier by games and charades— changed into saraos when music and dancing enlivened them. The reason the ladies gave such importance to these saraos was an economic one; being more costly and difficult to organize than the usual tertulia, they were out of reach for many who would have liked to offer them. Sometimes the expenses were shared by the participants, but that was not thought to be in good taste. There is, nevertheless, another reason for the incentive and fascination those parties had for women.

Giving a dance in one's home not only displayed the flourishing financial state of the family, but also gave one the opportunity to exhibit a certain ability and mastery of a number of rather complicated dance steps imported from abroad. For some time now, the folkish fandango and seguidilla had been pushed aside to make room in the salons for other styles of dancing, affected and unfamiliar in Spain.

Some foreign travelers in Spain at the end of the century remarked on the difficulty Spanish women had in learning the correct way to do them. At the sound of some violins and oboes, there began a dance that shook the whole house, especially the contredance , which, according to Don Jacinto, was more like a 'running around' than a dance. Neither he nor his companion knew anything about French dance steps, but they were very amused to see how those ladies and gentlemen were exhausting themselves, instead of having fun.

The most talked about foreign dances were the allemande , the minuet and above all, the contredance. Although it is beyond the scope of this book to give an even approximate description of the figures and the subtleties that differentiated one dance from the other, it is interesting to mention that in the contredance there was such a gamut of subdivisions, that the study of them inspired. In fact, no handier device could have been found to initiate the cortejo than the pell-mell of one of those dances, as Cadalso, the satirist, aptly commented.

In this satire, the male dancer is referred to as the currataco or pirraca fop, coxcomb, jackanape , terms which, as a rule, ridiculed gentlemen of leisure who were somewhat lacking in imagination, who therefore had to rely on the conventional variations of the contredance to make some advances to their partners. Such was the purpose, for instance, of a figure of the dance called "the snail":. The lady will take with her left hand, the fop's right, she will turn around toward the inside, without letting his hand go; they will then take each other's hands; in this fashion they go around the room.

This is one of the favorite figures in the contredance, because it allows the partners to chat; thus all the dandies who wish to be considered expert in this art should learn by heart some verses to recite to their partners while the dance lasts. The idea of making flirtation easier is even more explicit in the description of the finale of "the little mill":.

After the final circular figure, the dancers return to their place; if it happens that the young lady's head gets dizzy with the many turns, as it does happen to most of them, the gentelman will have her lean her head on his chest until her dizziness disappears. The fatigue of the dancers and the passing of the night became tacit allies, adding an erotic touch to the atmosphere created by those complicated movements. The sketch of one of these situations is drawn efficiently in the directions for the "cake dance":.

One can see that at this dance, taking place in the small hours of the morning—with the damsels inclined here and there on the chairs of the hall: So and So's the guests were falling asleep. The tasty tidbits referred to in the above description must have been increasingly enlivening, to the point when, in the s, a. From the above one can surmise, and I myself wish to point out, that these balls spawned the majority of the extramarital relations of the day. In the so-called "contredance of the husbands," there is an allusion to its purpose as a cover-up of illicit love:.

In the second part, an arena is represented; the men enter charging all at once, while the women hold each other's hand from behind. Further on, in the same text—contrasting the elegance and the grace of the ladies brought up to show off their accomplishments with the lack of polish of "those women that could do nothing else but keep house and nurse children"—one finds:.

Besides the time spent in the laborious apprenticeship of these contortions, women were proud of the prestige they gained by knowing how to play an instrument, or how to sing. Singing was a new device for showing off that added to the financial splurge stimulated by eighteenth-century high living: The music teacher, who had to instruct the lady in the fashionable melodies of the day, became a must in the education of the accomplished lady. You know full well that when the teacher gives them the lesson, he is almost cheek to jowl with them, and this closeness cannot but be risky.

Why should they study music? Since none of our forefathers had taken pride in being a musician, let's follow their footsteps, rather than the example of those few who, in the name of fashion, want to introduce such license and moral laxity. Neither that sermon nor similar ones were enough to restrain the growing popularity of those fashions in the last quarter of the century. All the opposition did not succeed in discrediting the opinion that skill in singing, dancing or playing an instrument—unproduc-. There are some contemporary verses contrasting very expressively those two ideals of womanhood: The well-bred lady worthy citizen , useful to the State and talented, must, according to fashion's tenets, know how to sing and play an instrument.

The one who does not know how to dance with pixie movements a minuet or a contredance, or a decent allemande with its appropriate grimaces, will be considered rustic. Diverted by more important things, she must ignore what is linen or wool. It does not befall her to have a life of meanness and drudgery.

The abnegated woman is by all considered strong, but the modern lady can in other ways, with talent, be stronger. Once married, she can avoid the useless daily care of administering the servants with wisdom and economy. It was just that: One had constantly to buy new things, and pile up the old ones. Because fashions were changing so rapidly, the editor of The Censor , a popular periodical of the time, planned to add a supplementary gazette, to be issued twice a week, with information on the fashionable things and the ones that were falling out of style.

Up-to-date news will be given on the variations taking place in each of the fashions; of the different degrees of popularity or falling out that one will be noticing; and, above all, pains will be taken in advising on the day in which they are completely out. There was a definite tendency to glorify the new, the instant, the appearance; there was a yearning to show off, to "make believe.

Nor was much importance given to the quality and durability of adornments, furniture and clothes, in order to save on further expenses; the important thing was that they were different from the previous ones, modern, admired by others. To sum it up, it amounted to people and objects being used to create an aura of modernity.

In the case of objects, one might even say that the manufacture of all those new articles was infused with an ideal of the ephemeral. If the furniture was more expensive in the past it also lasted longer, and after having served for many years, the material of which it was made could be salvaged; that does not happen with the painted wallpaper, stools, sofas and other furniture they are making nowadays.

Heirlooms were not the things to have among people dazzled by foreign styles, who gave themselves airs of elegance. The traditional meals, up to then thought wholesome and sufficient, were sacrificed on the same altar, and the condiments of French cuisine implanted. People are as progressive as you can expect. Yesterday I had dinner in a home and it was not too bad: The idle show of offering unusual dinners and suppers had reached such a point of extravagance that it provoked criticism and caricatures:.

Order it on the spot, and tell the chef that a specialist says the pastiche should have handles to pick it up; ask him to leave out, on one side, the trunk, on the other, the tail. Gourmet foods had become, in some cases, a matter of competition among the ladies who wanted to be thought of as refined. The whim for some difficult-to-find food that other ladies might have served at their tables resulted in resentment and a diligent search by the cortejo, who was frequently asked to look for the desired delicacy.

You ladies have such an active school of caprice, that it suffices for you to find out that something special was served at another lady's table, to be green with envy and ail with melancholy, until the most faithful of your circle lay it at your feet, though it might have cost him a pound. I remember having seen in the market an artichoke out of season, being sold for an exorbitant price, as a result of two gentlemen's bidding; and the worst was that the poor devil that got caught did not get anything out of it, except having proven himself courteous with his capricious lady.

As far as attire was concerned, the two articles that revolutionized feminine fashion had to do with headgear and footwear. The complicated hairdos introduced by French fashion made it necessary to employ a daily coiffeur as an indispensable prestige symbol. All the ladies were dying to have a private hairdresser, and if he were French, and private, so much the better. The ceremony of the lady's coiffure had much importance in the amorous code of the cortejo, because the escort was also assisting—further proof of his interest in the beloved—the hairdresser in his work, by advising and suggesting suitable and novel ways to position his lady's curls.

The lady gets dressed I don't know whether the cortejo serves her as a chambermaid and goes to the dressing room. There, his presence is a requisite, otherwise my lady would not have her hair dressed. Bewail the coiffeur who, by ignorance or negligence, lets one hair out of place; or does not make a thick and luxuriant braid to come down her neck, although her hair be thin; or powders her hair too much or too little; or does not fasten gracefully the head ornament; or does not give the flowers an elegant and novel symmetry!

The cortejo, whose duty is to show in all these things a refined and exquisite taste, is the implacable judge of the smallest slip. He knows very well how the coiffeur set the curls of a more important lady, the day before. The ladies' coiffures were made far more expensive than one can imagine by some extra details imposed by fashion; sometimes the coiffures disguised a gallant language and there existed a nomenclature that classified them, according to the passions that ordinarily agitated the light hearts of the cortejos.

Thus one could dis-. One of the upholders of the neoclassic precepts in the theater: As far as footwear is concerned, it too acquired a greater importance than in bygone eras, when women wearing "much longer skirts that covered their feet completely, did not need to splurge on stockings and shoes. Likewise, we can find literary references indicating that a well-dressed foot constituted an erotic element. Although it may seem trivial, winning the right to show one's foot had been hard enough.

The queen's rejection of a fashion she found uncomfortable was interpreted as a blow to tradition, and resulted in a series of letters between the Spanish and the French courts, which revealed the unpopularity the queen had earned herself by her negative attitude. The traditionalists held that the preservation of the tontillo protected women from the risk of showing their feet and a bit of their ankles. On the contrary, this novelty of showing one's feet delighted Spanish ladies, proud as they always had been of the daintiness of their feet. A German traveler of the second half of the century, Modenhawer, wrote that the women of Cadiz took great pride in their footwear, which they ordered from Madrid.

He also told us that. Author of an interesting autobiography, written in a style akin to that of the great baroque writer, Quevedo — The shoes must be very tastefully embroidered in gold, silver or silk, making sure they have not been worn twice to successive, special occasions, lest the lady might be discredited as not very original and quite ordinary. Another extremely important addition to the lady's attire during the eighteenth century was the fan, an indispensable accessory in any gallant situation.

Handled expertly, it carried a kind of message, though puerile and conventional, as was all the amorous language of the eighteenth century. In no other article have fashion's whims penetrated more—to the consequent advantage of foreign countries, which are causing endless spending in our own—spending well employed, in the opinion of the ladies who have to fan themselves even in December. It was, in fact, one of the most popular luxury items; no lady had just a few fans, and it was considered indecorous not to have a new one at any ceremony at which one wanted to be noticed.

These showy objects, more than any other feminine accessory, embodied that urge of "showing off" I have been referring to; a desire which concealed, under fluctuating surfaces and changing decor, the actual emptiness and spiritual penury of the people concerned. No better final touch for the fashionable ladies than a fan to accompany their half-daring, half-coy maneuvers; in a word, a requisite object, for the preliminaries of a relationship with a cortejo or with a gallant aspiring to become one.

The way of opening and closing the fan, of whispering while waving it, of letting it fall to be picked up by an obliging gentleman, were all part of a complex ceremony of nonsense and triviality, bordering on bold gestures and movements. Perhaps the fan was the go-between of woman's modesty. Behind the shade of a fan, confidences and advances were suggested, peals of laughter heard, blushes feigned, promising glances passed, and faces drew near. In a graphic description of the fan as an insulator between the lovers and the rest of the people in a gathering, one reads:.

Even when taking a cup of chocolate and paying each other compliments, everything was harmony between them, so absorbed were they in each other. This lasted for more than an hour with many such asides behind the fan. The fan had become so inseparable from the lady that a writer, complaining about the ignorance of the ladies, proposed this mocking remedy:. I wish in every fan were painted a book with excerpts from the current ones being published. The ladies who don't have time to read, and who love so much to talk about sciences and literature would have found a way to cut a good figure and instruct themselves by refreshing their pretty heads.

Considering the frequency with which they changed fans for every occasion and the array they owned, by applying this author's suggestion they would have compiled quite a library. Though most did not have the exorbitant number of fans collected by the Queen Isabel de Farnesio, [55] the constant purchase of this accessory had become a superfluous must for the lady, one much feared by the husbands.

In a family squabble of the time, the wife, who had just bought a fan for sixty doubloons to use in "informal visits," answered her husband's complaint with a new demand: The complaints of husbands reluctant to satisfy the demands of their wives, and overwhelmed by the squandering that threatened the entire family's finances were very common in the literature of the period.

I'll return to this subject in my comments on the economic aspects of the cortejo. It was impossible for a man to remain solvent with all of his wife's expenses; this might have been one of the reasons a husband tolerated the gifts and compliments with which another person was entertaining his wife: According to testimonials, the stress on the family budget was indeed unbearable.

The creation of new needs was not limited to. What was bleeding the family income—and what differentiated the eighteenth century from the previous eras—was public entertainments. At the beginning of the Bourbon dynasty, the tendency to make oneself less rustic—as they were wont to say in those days—and more refined in manners, had not gone beyond the court circle.

To that circle, one owes the introduction of the Italian Opera in Madrid. In , after the enormous fire that destroyed the Royal Palace, Philip V and all of his court moved to the Palace del Buen Retiro; therein someone thought of organizing a beautiful and serene spectacle to soothe and lift the spirits of the ailing king.

This was to be achieved by inviting the famous singer Farinelli, who had reaped so much glory in his native Italy, in Germany, and in England. The Opera in the Buen Retiro was inaugurated in May Farinelli, its much acclaimed director, invited other famous Italian singers who, in their prolonged stay in Spain, corroborated by their example some gallant ways quite popular in their country. Ferdinand VI, Philip V's son, kept up the habit of listening to the Opera, and had the whole company follow the court to the various royal residences.

These efforts at urbanization and increases in public entertainments mainly coincided with the ministry of the Count of Aranda. When the Marquis of Villahermosa returned to Madrid in from abroad, where he had spent some time in diplomatic missions, he found the city almost unrecognizable. Streets, walks and gardens had been embellished, parties were frequent in well-to-do private homes, coffee houses and refreshment stands had been installed, and it was not unusual to see the ladies stopping their carriages at the doors of such establishments to have some refreshments.

This same aristocrat, shortly before his arrival, received an enthusiastic letter from the Duke of Medinasidonia. A friend of Voltaire, he was one of the main agents in the expulsion of the Jesuits in The promenade in the Retiro Park is very lively. Near the lions' cage there is an establishment where they serve three kinds of drinks, sweets and chocolate; and one can sit down nearby in comfortable straw chairs.

In a straight line from that place, by the corner of the pond, there is another such establishment, with chairs. Yet another of the same kind is situated at the entrance of the Mayo walk, and there also, one finds tables to play cards and to drink. I can assure you I had never thought to see our country like this. Aranda deserves our applause and is an honor to our class. But the austere Charles III refused; he probably detected in her—with a certain uneasiness—that bent towards wantonness and caprice that she was to display later on, becoming one of the most shameless and unpopular queens.

Here is a description of one of these much-frequented feasts the queen was missing. They serve soup, roast, some seasoned meats, all kinds of pastry and some ragouts ; the lack of space and the kind of food served doesn't permit as elegant a service as with the desserts, but good enough, considering that there are two hundred people having dinner from eleven p.

The ladies, in particular, stand out with their elaborate hairdos; the dominoes and the gowns worn to a previous dance are discarded, and find new owners in the sedate people, who go there just to look around. At the first ball there were only a few over six hundred people, because the bigots did not dare to go and many did not even allow their wives to go.

Among them were those who, as a rule, let their wives go to dances organized by women who had been their maids and whose houses are not much better than brothels, but seeing how well and orderly things turned out, and seeing that everybody behaved well, including those who did not have the obligation to do so, everybody was allowed to enter, so that the number of guests soared to eighteen hundred. The number of people in costume increases by the day; the theater hardly holds the ones who are supposed to dance, and so they barely move at the sound of the instruments.

There are usually two. They were models to be imitated, observed and envied by the ladies of lesser quality, who were always ready to copy their gestures, their language and their manners with men. The attendance at the theaters increased, also, by including all social classes. Few women would let themselves be excluded from any spectacle that any other woman could attend.

All this weighed heavily on the family budget. Public entertainment, theaters, bullfights, etc. Add to these, the Lenten concerts, the opera season, the acrobatics, the magic lantern, the birth of Punchinello and other trickery of the sort. Without taking into account the teas and the balls with shared expenses and other popular diversions of this type, without mentioning private parties, because who is going to calculate the cost of just those?

In many commentaries on this phenomenon of generalized striving for social recognition in all strata of society, the reason invoked for its censure was the leveling power of money. People were being judged more on their appearance than on birth. Nothing easier than to be mistaken on the merits of the ones who have acquired something or whose families have been somebody.

Thus it seems that embroidery, jewels and laces fix and determine the degree of glory each has to enjoy in the world. A Letter on the Harmful Excesses of Luxury by Manuel Romero del Alamo revealed the apprehension some felt, towards the end of the century, at the subversion of traditional values, brought about by the spreading of this phenomenon. It has gradually grown in wastefulness and squander, especially lately. It has spread as a fire, devastating the summer crops. The spread of luxury in the capital, cities and towns has caused the confusion of common folk with the distinguished, the artist with the gentleman, the latter with the nobleman and the nobleman with the grandee.

Does it not often happen that a common woman, by the adornment of her person and her fashionable dress illicitly earned , when seen in public, putting on airs, ensnares the unwary and gains their respect while the decent woman is despised by everybody? From these testimonials, one can deduce a point essential to this study; given the growing prestige money was bringing, women no longer gave importance to the nobility or the social position of their future husbands, as long as they could afford to keep them at the social level they strove for and demanded.

- Living Through Grief: Strength and hope in time of loss (Lion Pocketbooks).

- 🔆 Free Downloadable Books For Kindle Fire Antología Del Machismo Ilustrado Spanish Edition.

- Сведения о продавце;

- No customer reviews;

- AntologÃa del machismo: www.newyorkethnicfood.com: Books.

All that women demand at present, as a rule, is a husband who can satisfy their insatiable appetite for luxuries: The compulsion, even more common, of showing off the symbols that money conferred, was a coercion women started to use on men—as we have seen in the example of the wife asking for another fan, hinging her case on the argument that she did not want people to consider him stingy. The general rule was that the husband who did not wish to stand out as old fashioned, rustic or poorly off— very common epithets in that time—resigned himself to his wife's reckless spending.

Three types of men don't go to the ball: This pressure seemed to succeed, as not only the wife, but also her family—with their demands—intensified the striving:. If the bride is not bedecked beyond the financial means of the husband, or if she does not satisfy the pretentiousness of her relations, it becomes a matter of honor; one has to spend more than one can afford, as it is base to live according to one's means. As the century unfolded, one could perceive in the marital complaints about wives' squandering, a certain getting used to it, a gradual resignation before the new evil, as if it were an inevitable calamity of the times one had to put up with.

Do you think that I married the jewels and that frippery you women fancy, or you yourself? That vanity of yours was so overpowering that I had to thank heaven for controlling my displeasure, lest everybody insinuate I didn't care for you. Thus, not caring for a person was confused with not doing the utmost in raising her to an economic level far superior to the one she might have been born in.

In previous centuries, the fear of being reputed as an ostentatious spendthrift had restrained matrons; but now the needle of being thought miserly, uncivilized, and not up with the times tormented husbands, whose authority was being questioned for the first time. And where shall we end if we continue in this way? I have an income of only two thousand ducats; five hundred go on the carriage, three hundred on the house, that makes eight hundred already; two hundred are taken up by my lady's coiffeur; here you have a thousand gone already. Now let's get into the daily expense of meals and servants, that does not certainly stop at the thousand; refreshments more than four hundred, theater tickets, not lower than two hundred; I am already spending far more than I can afford.

The wife turned on him in a way quite unknown in writings of the previous centuries. If your Lordship did not have enough means to support a lady of my status, why did you ask for my hand? Your lordship should have married a water carrier and you would have got away with buying four yards of ribbon, a silver hairpin and a cotton underskirt. In the arrogant tone of the speaker, there appears another aspect of the change in mentality; the repugnance of women to be taken for unrefined simpletons.

Few women were content to keep their place in a given social circle; the urge to imitate the upper classes was compelling. Do you expect me to bear seeing other women wearing a foot of lace on their gowns, while I see myself shrouded in a flannelette dress? People had discovered that it was possible to feign gentility. One could escape one's sphere by following the fashion; everything depended on cleverly giving the right impression, on appearing genteel. An author, in a text directed to the fashionable ladies, mocked those at the opposite pole of the thrifty homemakers of bygone days.

It is to you one owes the elimination of that gross abuse by which a married man earning twelve reales a day, had his wife clean, cook and bring up the children, letting them know that nowadays this wage is hardly enough to pay for your trinkets and that you were born to be ladies. Further on in the text, he scoffed again at the idea that housework is not proper for ladies, but for maids:.

Love Customs in Eighteenth-Century Spain

You have been relieved of those ordinary domestic chores assigned to maids who are organized for this type of work. The contemptuous comparison with Basque women is very meaningful. Rusticity, as opposed to civility, was a trait of the provincial. It has to be emphasized that the desirable styles were characteristically urban; gentility did not agree with the image of the woman brought up in the country or in the provinces, unable to elegantly fit into the ways of the city; therefore, this image was rejected. What mattered, then, was not a noble surname or irreproachable conduct, but rather the prestige given by the ability to conform to fashion.

The dichotomy of nobleman-plebian was shifting towards a different scale of values, found in the opposition between provincial and city styles. Around these two poles were grouped, respectively, the traditionalists and the moderns. The former tended to believe that the purest and most valuable essence of womanhood was to be found only in the recesses of towns and villages not overrun by immorality.

They felt certain that the provinces were the fountainhead of honest women of marriageable age. In this place the girls marry according to their means. One will not find here specimens of that frail youth, corrupt and doused in perfume, noisy, petulant, idle, gabbing and fatuous, like the ones I saw contredancing in the Puerta del Sol.

Women who wished to marry "in the old style" had better remain in their native town; but many of the provincial ladies, and sometimes their parents, were tempted to escape this obscure life and try a more glittering one. The capital's high life, of which echoes began to spread by word of mouth and publications to the remotest corners of Spain, had aroused the imagination of the wealthy among the country dwellers. Many did move to Madrid, and what most surprised them at first was the luxuriousness of women's attire.

One of these provincial gentlemen, bewildered and shocked, commented:. One of the foremost eighteenth-century dramatists and writers; a forceful reformer of the theater, according to neoclassic tenets. A small town in the province of Toledo. Among the remains of a better past, it hosts a hospital designed by El Greco, and in it, two of his paintings. Look at those women! I wonder whether a beneficial society has been formed, where they are distributing shoes, exclusive skirts, velvet and lace mantillas.

Full Books Download Pdf Antología Del Machismo Ilustrado Spanish Edition By Marco Lítico B00cxr4som

Madrid implacably set the pattern for all the others to follow, and many of the country folk who visited the capital felt out of place, complaining of being forever reminded of their rusticity. Since we cannot enjoy all the advantages of the capital, why don't they leave us alone, satisfied with what we are and what we have, instead of flinging our rusticity in our faces. Others bore with these jeers, determined to settle in Madrid, even if it were temporary. The reason for this persistence was not only to apply for a position or to study, as in the past, but also, and sometimes only, to rid oneself and one's children of the note of rusticity; to put on easy and genteel airs.

Nonetheless, luck did not always strike the country damsel, who came to the city accompanied by her rich father, to look for a suitable husband. But no definite results were to be seen. Grupo Editorial Universitario Granada Language: Be the first to review this item Would you like to tell us about a lower price?

I'd like to read this book on Kindle Don't have a Kindle? Share your thoughts with other customers. Write a customer review. There's a problem loading this menu right now. Learn more about Amazon Prime. Get fast, free shipping with Amazon Prime. Get to Know Us. English Choose a language for shopping. Explore the Home Gift Guide. Amazon Music Stream millions of songs. Amazon Advertising Find, attract, and engage customers. Amazon Drive Cloud storage from Amazon.