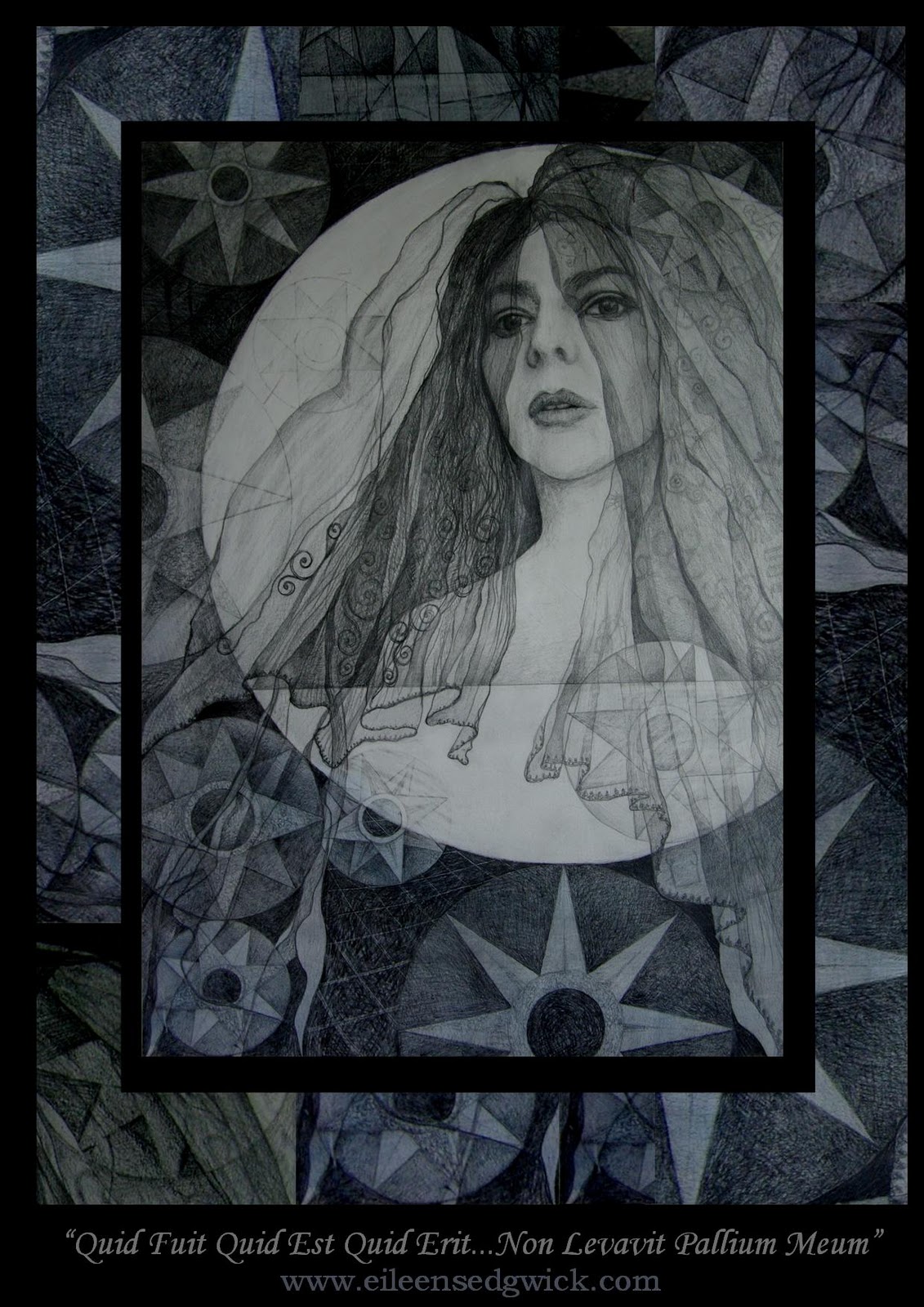

The Veil of Isis

In a peaceful sea, and among the playing fish they came to Dartmouth in Totnes. There the ships bit the sands, and with merry hearts the warriors went ashore. It happened after many days that Brutus and his people were celebrating holy writs, with meat, with drink, and with merry glee sounds: Twenty strong giants descended the hills: They hurled huge stones and slew five hundred of the Trojans. But soon the fierce steel arrows of the Trojans whistled through the air, and blood began to spurt from their monstrous sides. They tried to fly; but those darts followed them swift and revengeful, as birds of prey winged with the dark feathers of death.

Nineteen were slain and Geog-magog, their leader was brought bound before Brutus, who ordered a wrestling match to be held between the giant and Corineus, a chieftain of his army. Corineus and the giant advanced towards each other, they yoked their arms and stood breast to breast. Their eyes gushed blood, their teeth gnashed like wild boars, their bones cracked. Now their faces were black and swollen, now red and flaming with rage. Geog-magog thrust Corineus off his breast and drawing him back broke three of his ribs with his mighty hand.

But Corineus was not overcome, he hugged the giant grimly to his waist, and grasping him by the girdle swung him over the cliff upon the rocks below. Which spot is called "Geog-magog's leap" to this day. And to Corineus, the conqueror, was given a dukedom, which was thence called Corinee and thence Cornwall. Brutus having conquered the giant off-spring of the treacherous sisters, built a New Troy, and erected temples to the great Diana, and caused her to be worshipped throughout the land. They are usually truths disguised in gaudy or grotesque garments, but so disguised that the most profound philosophers are often at a loss how to separate the tinsel from the gold.

But even when they remain insolvable enigmas, they are, at least, to be preferred to the etymological eurekas and tedious conjectures with which antiquarians clog the pages of history, and which are equally false and less poetical. My fable of Albion is derived from the ancient chronicles of Hugh de Genesis, an historiographer now almost forgotten, and is gravely advanced by John Hardyng, in his uncouth rhymes, as the source of that desire for sovereignty which he affirms to be a peculiarity of his own countrywomen.

It is worthy of remark that the boys of Wales still amuse themselves by cutting out seven enclosures in the sward, which they call the City of Troy, and dance round and between them as if in imitation of the revolution of the planets. In a poem by Taliesin, the Ossian of Wales, called The Appeasing, of Lhudd, a passage occurs, of which this is a literal translation:. Their skill is celebrated, they were the dread of Europe. They came over the Hazy Sea from the summer country, which is called Deffrobani , that is where Constinoblys now stands.

It maybe possible to reconcile these contradictions of history in its simplest state, to which I might add a hundred from later writers. That then the warlike race of Taliesin also migrated from another region of the East, and that their battles with the Scythians gave rise to the fables of Brutus and Magog; for it was a practice, common enough with illiterate nations, to express heroes in their war-tales by the images of giants.

But let us pass on from such dateless periods of guess-work, to that in which The White Island first obtained notice from those philosophers, and poets, and historians, whom now we revere and almost deify. THE north of the island was inhabited by wild hordes of savages, who lived upon the bark of trees, and upon the precarious produce of the chase; went naked, and sheltered themselves from the weather under the cover of the woods, or in the mountain caves.

The midland tribes were entirely pastoral. They lived upon the flesh and milk which their flocks afforded them, and clothed themselves in their skins. While the inhabitants of the south, who had been polished by intercourse with strangers, were acquainted with many of the arts of civilization, and were ruled by a priesthood which was second to none in the world for its learning and experience. They manured their ground with marl, and sowed corn, which they stored in thatched houses, and from which they took as much as was necessary for the day and having dried the ears, beat the grain out, bruised it, and baked it into bread.

They ate little of this bread at their banquets, but great quantities of flesh, which they either boiled in water, or broiled upon the coals, or roasted upon spits. They drank ale or metheglin, a liquor made of milk and honey, and sat upon the skins of wolves or dogs. They lived in small houses built in a circular form, thatched with rushes into the shape of a cone; an aperture being left by which the smoke might escape. Their dress was of their own manufacture.

A square mantle covered a vest and trousers, or a deeply-plaited tunic of braided cloth; the waist was encircled by a belt, rings adorned the second finger of each hand, and a chain of iron or brass was suspended from the neck. These mantles, at first the only covering of the Britons, were of one color, with long hair on the outside, and were fastened upon the breast by a clasp, with the poorer classes by a thorn. The heads were covered with caps made of rushes, and their feet with sandals of untanned skin; specimens of which are still to be met with-of the former in Wales, of the latter in the Shetland Isles.

The women wore tunics, wrought and interwoven with various colors, over which was a loose robe of coarser make, secured with brazen buckles. They let their hair flow at freedom, and dyed it yellow like the ladies of ancient Rome; and they wore chains of massive gold about their necks, bracelets upon their arms, rings upon their fingers. They were skilled in the art of weaving, in which, however, the Gauls had obtained a still greater proficience. The most valuable of their cloths were manufactured of fine wool of different tints, woven chequer-wise, so as to fall into small squares of various colors.

They also made a kind of cloth, which, without spinning or weaving, was, when worked up with vinegar, so hard and impenetrable, that it would turn the edge of the sharpest sword. They were equally famous for their linen, and sail-cloths constituted a great part of their trade.

- The Human Cell.

- El club del pudin (Spanish Edition)!

- Navigation menu.

- The Veil of Isis or Mysteries of the Druids.

- Mussolini (Italian Edition).

- The Veil of Isis: An Essay on the History of the Idea of Nature.

- The How To Get More Referrals Guide - when easy to ask, is no longer a task;

The flax having been whitened before it was sent to the loom, the unspun yarn was placed in a mortar where it was pounded and beaten into water; it was then sent to the weaver, and when it was received from him made into cloth, it was laid upon a large smooth stone, and beaten with broad-headed cudgels, the juice of poppies being mingled with the water.

For scouring cloths, they used a soap invented by themselves, which they made from the fat of animals and the ashes of certain vegetables. Distinct from these southern tribes, were the inhabitants of the Cassiterides, who wore long black garments, and beards falling on each side of their mouths like wings, and who are described by Pliny as "carrying staves with three serpents curling round like Furies in a tragedy. It is probable that the nudity of the northern nations did not proceed from mere barbarous ignorance. We know that savages are first induced to wear clothing, not from shame, but from vanity; and it was this passion which restrained them from wearing the skins of beasts, or the gaudy clothes of their civilized neighbors.

For it was their custom to adorn their bodies with various figures by a tedious and painful process. At an early age, the outlines of animals were impressed with a pointed instrument into the skin; a strong infusion of woad , a Gallic herb from which a blue dye was extracted was rubbed into the punctures, and the figures expanding with the growth of the body retained their original appearance. Like the South-Sea Islanders they esteemed that to be a decoration which we consider a disfigurement, and these tatooings which were used by the Thracicans and by the ancient inhabitants of Constantinople, and which were forbidden by Moses, Levit.

Like the Gauls, who endeavored to make their bright red hair rough and bristly not for ornament, but as a terror to their enemies, these Britons on the day of battle flung off their clothes, and with swords girded to their naked sides, and spear in hand, marched with joyful cries against their enemies. Also upon certain festivals they, with their wives and children, daubed themselves from head to foot with the blue dye of the woad and danced in circles bowing to the altar. But the Picts, or painted men, as the Romans named them, colored themselves with the juice of green grass.

Hunting was their favorite exercise and sport, and Britain which was then filled with vast swamps and forests afforded them a variety of game. The elephant and the rhinoceros, the moose-deer, the tiger and other beasts now only known in Eastern climes, and mammoth creatures that have since disappeared from the face of the earth made the ground tremble beneath their stately tread. The brown bear preyed upon their cattle, and slept in the hollow oaks which they revered. The hyenas yelped by night, and prowled round the fold of the shepherd.

See a Problem?

The beaver fished in their streams, and built its earthen towns upon their banks. And hundreds of wolves, united by the keen frosts of winter, gathered round the rude habitations of men and howled from fierce hunger, rolling their horrible green eyes and gnashing their white teeth. Their seas abounded with fish, but since they held water sacred they would not, injure its inhabitants for they believed them to be spirits. I will now consider the primeval state of trade in Britain, now the greatest commercial country in the world.

It was not long before they discovered the lead and tin mines of Cornwall and the Cassiterides, which would appear from several flint-headed tools called celts lately discovered within them to have been worked by the Britons themselves. And as they were wont to exchange the pottery of Athens for the ivory of Africa, and live Jews for the gold and jewels of the Greeks, so they bartered salt, earthenware and brazen trinkets with the Britons for tin, lead, and the skins of wild beasts.

Although they had supplied tin and amber for several years to the Greeks, Herodotus, who had visited Tyre, could only obtain very vague accounts as to the countries from which they had been obtained, and on making inquiries respecting cinnamon and frankincense, was explicitly informed that the first was procured by stratagem from the nests of birds built upon inaccessible crags, and the latter from a tree guarded by winged serpents. The Romans were also shipwrecked, and were drowned, but the patriot escaped to tell his tale at Tyre, and to receive from a grateful state the value of his cargo and an additional reward.

Thus monopoly being ended, the commerce of the Britons was extended. It also appears that chalk was an article of their trade, by this inscription which was found with many others near Zeland, A. Before describing the religion and superstitions of our earliest ancestors, which will bring me to the real purpose of this book, I will add a few remarks upon their manners and peculiarities. Curiosity, which is certainly the chief characteristic of all barbarous and semi-barbarous nations, was possessed by the Celts in so extraordinary a degree that they would compel travelers to stop, even against their wills, and make them tell some news, and deliver an opinion upon the current events of the day.

They would also crowd round the merchants in towns with the same kind of inquiries. But the great failing of these Celts was their hastiness and ferocity. Not content with pitched battles against their enemies abroad, they were always ready to fight duels with their friends at home. They feared nothing these brave men. They sang as they marched to battle, and perhaps to death. They shot arrows at the heavens when it thundered; they laughed as they saw their own hearts' blood gushing forth.

And yet they were plain and simple in their manners; open and generous, docile and grateful, strangers to low cunning and deceit, so hospitable that they hailed the arrival of each fresh guest with joy and festivities, so warm-hearted that they were never more pleased than when they could bestow a kindness.

Their code of morals, like those of civilized nations, had its little contradictions; they account it disgraceful to steal, but honorable to rob, and though they observed the strictest chastity, they did not blush to live promiscuously in communities of twelve. This extraordinary custom induced Caesar to assert that they enjoyed each other's wives in common; but in this he is borne out by no other authorities, and, indeed, there are many instances of this kind among barbarous nations, who love, apparently, to hide their real purity with a gross and filthy enamel.

Having thus briefly sketched the condition and employments of the early Britons--having proved that our ancestors were brave, and that their daughters were virtuous, I will now show you those wise and potent men of whom these poor barbarians were but the disciples and the slaves. It resembled them so closely in its sublime precepts, in its consoling promises, as to leave no doubt that these nations, living so widely apart, were all of the same stock and the same religion-that of Noah, and the children of men before the flood.

They worshipped but one God, and erected to him altars of earth, or unhewn stone, and prayed to him in the open air; and believed in a heaven, in a hell, and in the immortality of the soul. It is strange that these offsprings of the patriarchs should also be corrupted from the same sources, and should thus still preserve a resemblance to one another in the minor tenets of their polluted creeds.

As the Indian wife was burnt upon her husband's pyre, so, on the corpses of the Celtic lords, were consumed their children, their slaves, and their horses. And, like the other nations of antiquity, as I shall presently prove, the Druids worshipped the heavenly bodies, and also trees, and water, and mountains, and the signs of the serpent, the bull and the cross. From the sandy plains of Egypt to the icebergs of Scandinavia, the whole world has rung with the exploits of Hercules, that invincible god, who but appeared in the world to deliver mankind from monsters and from tyrants.

He -was really a Phoenician harokel , or merchant, an enterprising mariner, and the discoverer of the tin mines of the Cassiterides. He it was who first sailed through the Straits of Gibraltar, which, to this day, are called The Pillars of Hercules: It is gratifying to learn that his twelve labors were, in reality, twelve useful discoveries, and that he had not been deified for killing a wild beast and cleaning out stables. As the Chaldeans, who were astronomers, made Hercules an astronomer; and as the Greeks and Romans, who were warriors, made him a hero of battles; so the Druids, who were orators, named him Ogmius , or the Power of Eloquence, and represented him as an old man followed by a multitude, whom he led by slender and almost invisible golden chains fastened from his lips to their ears.

As far as we can learn, however, the Druids paid honors, rather than adoration to their deities, as the Jews revered their arch-angels, but reserved their worship for Jehovah. And, like the God of the Jews, of the Chaldees, of the Hindoos, and of the Christians, this Deity of the Druids had three attributes within himself, and each attribute was a god. Let those learn who cavil at the mysterious doctrine of the Trinity, that it was not invented by the Christians, but only by them restored from times of the holiest antiquity into which it had descended from heaven itself.

Although the Druids performed idolatrous ceremonies to the stars, to the elements, to hills, and to trees, there is a maxim still preserved among the Welsh mountaineers, which shows that in Britain the Supreme Being was never so thoroughly forgotten and degraded as he had been in those lands to which he first gave life.

But by that time, Druidism had begun to wane in Gaul, and to be deprived of many of its privileges by the growing intelligence of the secular power. It is generally acknowledged that there were no Druids in Germany, though Keysler has stoutly contested this belief and has cited an ancient tradition to the effect that they had Druidic colleges in the days of Hermio, a German Prince. The learned SeIden relates that some centuries ago in a monastery upon the borders of Vaitland, in Germany, were found six old statues which being exposed to view, Conradus Celtes, who was present, was of opinion that they were figures of ancient Druids.

They were seven feet in height, bare-footed, their heads covered with a Greek hood, a scrip by their sides and a beard descending from their nostrils plaited out in two divisions to the middle; in their hands a book and a Diogenes staff five feet in length; their features stern and morose; their eyes lowered to the ground.

Such evidence is mere food for conjecture. Of the ancient German priests we only know that they resembled the Druids, and the medicine-men of the American aborigines in being doctors as well as priests. The Druids possessed remarkable powers and immunities. Like the Levites, the Hebrews, and the Egyptian priests they were exempted from taxes and from military service. They also annually elected the magistrates of cities: Thus the Druids were regarded as the real fathers of the people. The Persian Magi were entrusted with the education of their sovereign; but in Britain the kings were not only brought up by the Druids, but also relieved.

These terrible priests formed the councils of the state, and declared peace or war as they pleased. The poor slave whom they seated on a throne, and whom they permitted to wear robes more gorgeous even than their own was surrounded, not by his noblemen, but by Druids. He was a prisoner in his court, and his jailors were inexorable, for they were priests.

There was a Chief Druid to advise him, a bard to sing to him, a sennechai , or chronicler, to register his action in the Greek character, and a physician to attend to his health, and to cure or kill him as the state required. All the priests in Britain and all the physicians, all the judges and all the learned men, all the pleaders in courts of law and all the musicians belonged to the order of the Druids.

It can easily be conceived then that their power was not only vast but absolute. It may naturally excite surprise that a nation should remain so barbarous and illiterate as the Britons undoubtedly were, when ruled by an order of men so polished and so learned. But these wise men of the West were no less learned in human hearts than in the triplet verses, and oral of their.

They knew that it is almost impossible to bring women and the vulgar herd of mankind to piety and virtue by the unadorned dictates of reason. They knew the admiration which uneducated minds have always for those things which they cannot understand. They knew that to retain their own sway they must preserve these barren minds in their abject ignorance and superstition. In all things, therefore, they endeavored to draw a line between themselves and the mass. In their habits, in their demeanor, in their very dress.

They wore long robes which descended to the heel, while that of others came only to the knee; their hair was short and their beards long, while the Britons wore but moustaches on their upper lips, and their hair generally long. Instead of sandals they wore wooden shoes of a pentagonal shape, and carried in their hands a white wand called slatan drui' eachd , or magic wand, and certain mystical ornaments around their necks and upon their breasts. It was seldom that anyone was found hardy enough to rebel against their power.

For such was reserve a terrible punishment. It was called Excommunication.

It was one of the most horrible that it is possible to conceive. At the dead of night, the unhappy culprit was seized and dragged before a solemn tribunal, while torches, painted black, gave a ghastly light, and a low hymn, like a solemn murmur, was chanted as he approached. Clad in a white robe, the Arch-Druid would rise, and before the assembly of brother-Druids and awestricken warriors would pronounce a curse, frightful as a death warrant, upon the trembling sinner.

Then they would strip his feet, and he must walk with them bare for the remainder of his days; and would clothe him in black and mournful garments, which he must never change. Then the poor wretch would wander through the woods, feeding on berries and the roots of trees, shunned by all as if he had been tainted by the plague, and looking to death as a salvation from such cruel miseries. And when he died, none dared to weep for him; they buried him only that they might trample on his grave. Even after death, so sang the sacred bards, his torments were not ended; he was borne to those regions of eternal darkness, frost, and snow, which, infested with lions, wolves, and serpents, formed the Celtic hell, or Ifurin.

These Druids were despots; and yea they must have exercised their power wisely and temperately to have retained so long their dominion over a rude and warlike race. There can be little doubt that their revenues were considerable, though we have no direct means of ascertaining this as a fact.

However, we know that it was customary for a victorious army to offer up the chief of its spoils to the gods; that those who consulted the oracles did not attend them empty-handed, and that the sale of charms and medicinal herbs was a constant trade among them. Although all comprehended under the one term DRUID, there were, in reality, three distinct sects comprised within the order.

First, the Druids or Derwydd, properly so called. These were the sublime and intellectual philosophers who directed the machineries of the state and the priesthood, and presided over the dark mysteries of the consecrated groves. It was their province to sing the praises of horses in the warrior's feasts, to chant the sacred hymns like the musician's among the Levites, and to register genealogies and historical events. The Ovades or Ovydd, derived from ov , raw, pure, and ydd , above explained were the noviciates, who, under the supervision of the Druids, studied the properties of nature, and offered up the sacrifices upon the altar.

Thus it appears that Derwydd, Bardd, and Ovydd, were emblematical names of the three orders of Druidism. The Derwydd was the trunk and support of the whole; the Bardd the ramification from that trunk arranged in beautiful foliage; and the Ovydd was the young shoot, which, growing up, ensured a prospect of permanency to the sacred grove. The whole body was ruled by an Arch-Druid elected by lot from those senior brethren who were the most learned and the best born.

Let us now consider these orders under their respective denominations-Derwydd, Bardd, Ovyd; and under their separate vocations, as philosophers musicians, and priests. Under the head of the Ovydd, I shall describe their initiatory and sacrificial rites, and shall now merely consider their acquirements, as instructors, as mathematicians, as law-givers and as physicians.

Ammianus Marcellinus informs us that the Druids dwelt together in fraternities, and indeed it is scarcely possible that they could have lectured in almost every kind of philosophy and preserved their arcana from the vulgar, unless they had been accustomed to live in some kind of convent or college.

They were too wise, however, to immure themselves wholly in one corner of the land, where they would have exercised no more influence upon the nation than the Heads and Fellows of our present universities. While some lived the lives of hermits in caves and in hollow oaks within the dark recesses of the holy forests; while others lived peaceably in their college-home, teaching the bardic verses to children, to the young nobles, and to the students who came to them from a strange country across the sea, there were others who led an active and turbulent existence at court in the councils of the state and in the halls of nobles.

In Gaul, the chief seminaries of the Druids was in the country of the Carnutes between Chartres and Dreux, to which at one time scholars resorted in such numbers that they were obliged to build other academies in various parts of the land, vestiges of which exist to this day, and of which the ancient College of Guienne is said to be one. When their power began to totter in their own country, the young Druids resorted to Mona, now Anglesea, in which was the great British university, and in which there is a spot called Myrfyrion , the seat of studies.

The Druidic precepts were all in verses, which amounted to 20, in number, and which it was forbidden to write.

MYSTERIES OF THE DRUIDS

Consequently a long course of preparatory study was required, and some spent so much as twenty years in a state of probation. These verses were in rhyme, which the Druids invented to assist the memory, and in a triplet form from the veneration which was paid to the number three by all the nations of antiquity. In this the Jews resembled the Druids, for although they had received the written law of Moses, there was a certain code of precept among them which was taught by mouth alone, and in which those who were the most learned were elevated to the Rabbi.

The mode of teaching by memory was also practised by the Egyptians and by Lycurgus, who esteemed it better to imprint his laws on the minds of the Spartan citizens than to engrave them upon tablets. So, too, were Numa's sacred writing buried with him by his orders, in compliance perhaps with the opinions of his friend Pythagoras who, as well as Socrates, left nothing behind him committed to writing.

It was Socrates, in fact, who compared written doctrines to pictures of animals which resemble life, but which when you question them can give you no reply. But we who love the past have to lament this system. When Cambyses destroyed the temples of Egypt, when the disciples of Pythagoras died in the Meta-pontine tumults, all their mysteries and all their learning died with them.

So also the secrets of the Magi, the Orpheans and the Cabiri perished with their institutions, and it is owing to this law of the Druids that we have only the meagre evidence of ancient authors and the obscure emblems of the Welsh Bards, and the faint vestiges of their mighty monuments to teach us concerning the powers and direction of their philosophy. There can be no doubt that they were profoundly learned.

This is a fac-simile of their alphabet as preserved in the Thesaurus Muratori. Both in the universities of the Hebrews, which existed from the earliest times, and in those of the Brachmans it was not permitted to study philosophy and the sciences, except so far as they might assist the student in the perusal and comprehension of the sacred writings. But a more liberal system existed among the Druids, who were skilled in all the arts and in foreign languages. For instance, there was Abaris, a Druid and a native of the Shetland Isles who traveled into Greece, where he formed a friendship with Pythagoras and where his learning, his politeness, his shrewdness, and expedition in business, and above all, the ease and elegance with which he spoke the Athenian tongue, and which so said the orator Himerius would have made one believe that he had been brought up in the academy or the Lycceum, created for him as great a sensation as that which was afterwards made by the admirable Crichton among the learned doctors of Paris.

It can easily be proved that the science of astronomy was not unknown to the Druids. One of their temples in the island of Lewis in the Hebrides, bears evident signs of their skill in the science. Every stone in the temple is placed astronomically. The circle consists of twelve equistant obelisks denoting the twelve signs of the zodiac. The four cardinal points of the compass are marked by lines of obelisks running out from the circle, and at each point subdivided into four more.

The range of obelisks from north, and exactly facing the south is double, being two parallel rows each consisting of nineteen stones. A large stone in the centre of the circle, thirteen feet high, and of the perfect shape of a ship's rudder would seem as a symbol of their knowledge of astronomy being made subservient to navigation, and the Celtic word for star, ruth-iul, "a-guide-to-direct-the-course," proves such to have been the case.

This is supposed to have been the winged temple which Erastosthenes says that Apollo had among the Hyperboreans--a name which the Greeks applied to all nations dwelling north of the Pillars of Hercules. But what is still more extraordinary, Hecateus makes mention that the inhabitants of a certain Hyperborian island, little less than Sicily, and over against Celtiberia--a description answering exactly to that of Britain--could bring the moon so near them as to show the mountains and rocks, and other appearances upon its surface.

According to Strabo and Bochart, glass was a discovery of the Phoenicians and a staple commodity of their trade, but we have some ground for believing that our philosophers bestowed rather than borrowed this invention. Pieces of glass and crystal have been found in the cairns, as if in honor to those who invented it; the process of vitrifying the very walls of their houses, which is still to be seen in the Highlands prove that they possessed the art in the gross; and the Gaelic name for glass is not of foreign but of Celtic extraction, being glasine and derived from glas-theine , glued or brightened by fire.

- Paradox: Traveler (Time Paradox Series Book 1)?

- Annies Faith: A Search for Meaning.

- Veil of Isis - Wikipedia.

- The Veil of Isis | Gnostic Muse.

- Veil of Isis.

- THE VEIL OF ISIS;?

We have many wonderful proofs of the skill in mechanics. The clacha-brath , or rocking-stones, were spherical stones of an enormous size, and were raised upon other flat stones into which they inserted a small prominence fitting the cavity so exactly, and so concealed by loose stones lying around it, that nobody could discern the artifice.

Thus these globes were balanced so that the slightest touch would make them vibrate, while anything of greater weight pressing against the side of the cavity rendered them immovable. In Iona, the last asylum of the Caledonian Druids, many of these clacha-brath one of which is mentioned in Ptolemy Hephestion's History, Lib. In Stonehenge, too, we find an example of that oriental mechanism which is displayed so stupendously in the pyramids of Egypt. Here stones of thirty or forty tons that must have been a draught for a herd of oxen, have been carried the distance of sixteen computed miles and raised to a vast height, and placed in their beds with such ease that their very mortises were made to tally.

The temples of Abury in Wiltshire, and of Carnac in Brittany, though less perfect, are even more prodigious monuments of art. It is scarcely to be wondered at that the Druids should be acquainted with the properties of gunpowder, since we know that it was used in the mysteries of Isis, in the temple of Delphi, and by the old Chinese philosophers. Lucan in his description of a grove near Marseilles, writes: In Ossian's poem of Dargo the son of the Druid of Bet , similar phenomenon are mentioned, and while the Celtic word lightning is De'lanach , "the flash or flame of God," they had another word which expresses a flash that is quick and sudden as lightning-- Druilanach , "the flame of the Druids.

It would have been fortunate for mankind had the monks of the middle ages displayed the wisdom of these ancient priests in concealing from fools and madmen so dangerous an art. All such knowledge was carefully retained within the holy circle of their dark caves and forests and which the initiated were bound by a solemn oath never to reveal.

On the seventh day, like the first patriarchs, they preached to the warriors and their wives from small round eminences, several of which yet remain in different parts of Britain. Their doctrines were delivered with a surpassing eloquence and in triplet verses, many specimens which are to be found in the Welsh poetry but of which these two only have been preserved by the classical authors.

Once every year a public assembly of the nation was held in Mona at the residence of the Arch-Druid, and there silence was no less rigidly imposed than in the councils of the Rabbi and the Brachmans. If any one interrupted the orator, a large piece of his robe was cut off--if after that he offended, he was punished with death. To enforce Punctuality, like the Cigonii of Pliny, they had the cruel custom of cutting to pieces the one who came last.

Their laws, like their religious precepts, were at first esteemed too sacred to be committed to writing-the first written laws being those of Dyrnwal Moelmud, King of Britain, about B. The Manksmen also ascribe to the Druids those excellent laws by which the Isle of Man has always been governed. The Magistrates of Britain were but tools of the Druids, appointed by them and educated by them also; for it was a law in Britain that no one might hold office who had not been educated by the Druids.

The Druids held annual assizes in different parts of Britain for instance at the monument called Long Meg and her Daughters in Cumberland and at the Valley of Stones in Cornwall as Samuel visited Bethel and Gilgal once a year to dispense justice. There they heard appeals from the minor courts, and investigated the more intricate cases, which sometimes they were obliged to settle by ordeal. The rocking-stones which I have just described, and the walking barefoot through a fire which they lighted on the summit of some holy hill and called Samb'in , or the fire of peace, were their two chief methods of testing the innocence of the criminal, and in which they were imitated by the less ingenious and perhaps less conscientious judges of later days.

For previous to the ordeal which they named Gabha Bheil , or "the trial of Beil," the Druids used every endeavor to discover the real merits of the case, in order that they might decide upon the verdict of Heaven--that is to say, which side of the stone they should press, or whether they should anoint his feet with that oil which the Hindoo priests use in their religious festivals, and which enables the barefoot to pass over the burning wood unscathed. We may smile at another profanity of the Druids who constituted themselves judges not only of the body but of the soul. But as Mohammed inspired his soldiers with sublime courage by promising Paradise to those who found a death-bed upon the corpses of their foes, so the very superstitions, the very frauds of these noble Druids tended to elevate the hearts of men towards their God, and to make them lead virtuous lives that they might merit the sweet fields of Fla'innis , the heaven of their tribe.

Never before since the world, has such vast power as the Druids possessed been wielded with such purity, such temperance, such discretion. When a man died a platter of earth and salt was placed upon his breast, as is still the custom in Wales and in the North of Britain. The earth an emblem of incorruptibility of the body--the salt an emblem of the incorruptibility of the soul. A kind of court was then assembled round the corpse, and by the evidence of those with whom he had been best acquainted, it was decided with what funeral rites he should be honored.

If he had distinguished himself as a warrior, or as man of science, it was recorded in the death-song; a cairn or pile of sacred stones was raised over him, and his arms and tools or other symbols of his profession were buried with him. If his life had been honorable, and if he had obeyed the three grand articles of religion, the bard sang his requiem on the harp, whose beautiful music alone was a pass-port to heaven.

The Veil of Isis: An Essay on the History of the Idea of Nature by Pierre Hadot

It is a charming idea, is it not? The soul lingering for the first strain which might release it from the cold corpse, and mingle with its silent ascent to God. Read how the heroes of Ossian longed for this funereal hymn without which their souls, pale and sad as those which haunted the banks of the Styx, were doomed to wander through the mists of some dreary fen.

When this hymn had been sung, the friends and relatives of the deceased made great rejoicings, and this it was that originated those sombre merry-makings so peculiar to the Scotch and Irish funerals. In the philosophy of medicine, the Derwydd were no less skilled than in sciences and letters.

They knew that by means of this divine art they would possess the hearts as well as the minds of men, and obtain not only the awe of the ignorant but also the love of those whose lives they had preserved. Their sovereign remedy was the missoldine or mistletoe of the oak which, in Wales, still bears its ancient name of Oll-iach , or all-heal, with those of Pren-awr , the celestial tree, and Uchelwydd , the lofty shrub.

- Nights I Cant Remember, Friends Ill Never Forget;

- Dark & Merciless Things (A Collection of 10 Short Stories).

- The Veil of Isis — Pierre Hadot | Harvard University Press.

- ?

- .

- .

- Raining Down On Me (Seeking Heart Teen Series Book 3)!

The Divine Mother is not a woman, nor is she an individual. She is in fact an unknown substance. Any form that she takes disintegrates afterwards — that is love. The Divine Mother , loving matrix and substance of the universe, always disintegrates her form, her form is always unknown. Known as Hecate, Coatlique, Kali, the female goddesses of death. Death is the final crown of everyone, is unknown, and yet contemplating her mystery is the greatest aspiration of the sincere seeker of the mysteries of life and death. The Prakriti is the cosmic womb of creation.

An example is Louis-Ernest Barrias 's sculpture Nature Unveiling Herself Before Science , in which the multiple breasts are omitted and the Isis-figure wears a scarab on her gown that hints at her Egyptian background. Another interpretation of Isis's veil emerged in the late 18th century, in keeping with the Romantic movement that was developing at the time, in which nature constitutes an awe-inspiring mystery rather than prosaic knowledge.

This interpretation was influenced by the ancient mystery initiations dedicated to Isis that were performed in the Greco-Roman world. To do so, he interpreted the first statement on the statue at Sais, "I am all that has been and is and shall be," as a declaration of pantheism , in which nature and divinity are identical. Reinhold claimed the public face of Egyptian religion was polytheistic , but the Egyptian mysteries were designed to reveal the deeper, pantheistic truth to elite initiates.

The Veil of Isis

He also said the statement " I am that I am ", spoken by the Jewish God in the Book of Exodus , meant the same as the Saite inscription and indicated that Judaism was a descendant of the ancient Egyptian belief system. Immanuel Kant connected the motif of Isis's veil with his concept of the sublime , saying, "Perhaps no one has said anything more sublime, or expressed a thought more sublimely, than in that inscription on the temple of Isis Mother Nature.

The ecstatic nature of ancient mystery rites themselves contributed to the focus on emotions. He said it prepared the initiate to confront the awe-inspiring power of nature at the climax of the rite. Similarly, a frontispiece by Henry Fuseli , made for Erasmus Darwin 's poem The Temple of Nature in , explicitly shows the unveiling of a statue of Isis as the climax of the initiation. Helena Blavatsky 's book Isis Unveiled , one of the foundational texts for the esoteric belief system of Theosophy , used the metaphor of the veil as its title.

Isis is not prominent in the book, but in it Blavatsky said that philosophers try to lift the veil of Isis, or nature, but see only her physical forms. She added, "The soul within escapes their view; and the Divine Mother has no answer for them," implying that theosophy will reveal truths about nature that science and philosophy cannot. The "Parting of the Veil", "Piercing of the Veil", "Rending of the Veil" or "Lifting of the Veil" refers, in the Western mystery tradition and contemporary witchcraft , to opening the "veil" of matter, thus gaining entry to a state of spiritual awareness in which the mysteries of nature are revealed.

In ceremonial magic , the Sign of the Rending of the Veil is a symbolic gesture performed by the magician with the intention of creating such an opening. It is performed starting with the arms extended forwards and hands flat against each other either palm to palm or back to back , then spreading the hands apart with a rending motion until the arms point out to both sides and the body is in a T shape.

After the working is complete, the magician will typically perform the corresponding Sign of the Closing of the Veil, which has the same movements in reverse. Media related to Nature with a veil at Wikimedia Commons. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.