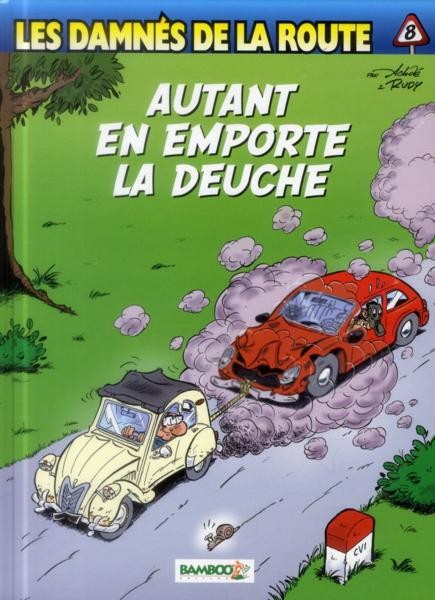

Les damnés de la route – tome 1 - On achève bien les 2 chevaux (French Edition)

Rated M for language and safety. If you don't like what I do, don't read it. M - French - Adventure - Chapters: Road to a Master by Fee-fi-fo-fum reviews What if Delia had stepped in and made sure that Ash was prepared for his journey? After all, what kind of mother will allow her only son to travel a dangerous world ill-prepared? Smarter Ash, more prepared Ash.

A mix of the games and the anime. She did not consider the consequences of what her actions might bring, or the danger she might be in. A chance run in with a single irreverent, and possibly crazy, person in a bar changes the course of fate for an entire galaxy. Now Rated M - Just in case! Chapter 01 - Edited. Passageways by jerrway69 reviews Hogwarts Castle decides to interfere in the lives of two of its students to change the past and future from a terrible war and giving the pair an opportunity to find something more than just protection within its walls.

A bewildered Ash can only go with the flow as he begins his journey to become the most powerful Pokemon Trainer the world as ever seen. Rated M for swearing, violence and future sexual situations. Shadow of the Devil by dripley11 reviews A normal life; that's what most say they want. Naruto got that wish when he began attending Kuoh academy four months ago.

Then one day he dies just as he lived, protecting his new friend Issei from a man claiming that his friend was now something called a Stray Devil and spouting off some nonsense about being a Fallen Angel. Harry; How would the wizarding world react to a Boy Who Lived who is much different from what they expected? One that is set to change the course of the magical world forever? But that is not the only new discoveries for Harry and Hermione. What will this mean for the future? And what does it mean to be a Neko's Mate?

I'm Still Here by kathryn reviews The second war with Voldemort never really ended, and there were no winners, certainly not Harry Potter who has lost everything. What will Harry do when a ritual from Voldemort sends him to another world? How will he manage in this new world in which he never existed, especially as he sees familiar events unfolding? Rise of a Master: Get ready Sinnoh because here comes Ash Ketchum! Sure, he didn't expect to be another girl's mentor, but maybe it won't be so bad He realized his mistakes and rectifies them. Now, no more starting over.

Beware Sinnoh, for this time Ash Ketchum is here to win. Tout le monde sauf une personne, un vampire: Black Joker by dragonliege reviews It's been 3 months since Aizen's defeat and Ichigo's powers have faded. Pangs of pain constantly plague him, accompanied by bursts of unfamiliar reiatsu. One day, his ability to see spirits returns in time for him to see a Hollow chasing a Plus. What followed would change his life forever It has no leaning or even understanding of good or evil.

Harry Potter fell off the grid half a decade before, after an explosion seared the earth of Privet Drive. No magic could find him. Their final hope led them to him, but what they found was Road of the Master by Lezaroth reviews Ash, a boy who was born in Pallet Town, started his journey together with his friends.

History records him as the true Aura Guardian. Some know him as the Chosen One, others know him as their Hero. This is the story of Ash Ketchum and his friends. A story of their journey to become a master. Last Second Savior by plums reviews While leading the final charge against a retreating Dark Lord, Harry is thrown through a destabilized Demon Portal, landing on a strange world in a galaxy far far away. Master of the Force: Book 1 by smaster28 reviews An infant Harry is taken in and raised by an ancient Jedi master Fay after the death of his parents.

A budding Jedi Harry tackles the problems of Wizarding world before embarking on a journey that would change the fate of the Jedi order and the Galactic Republic. Wizard Runemaster by plums reviews A Weapon. But now… a loose end. Harry Potter resolves to destroy the enemies who betrayed him on his terms, only to find all his plans torn asunder when he's summoned to a new world plagued with the same enemies as his own. Secrets by fujin of shadows reviews Formely known and the re write of Secrets of the Aura Guardian.

Secrets, they are very delicate, some secrets are dangerous, some our harmless, some are the keys to success and love. Ash has some secrets that are all of those.. Ashxoc one sided Ashxharem.

Menu de navigation

Teaser for next chapter is out The Ninth Fist by Agurra of the Darkness reviews Betrayed by the people he vowed to protect Naruto finds himself in a new world with new skills. Searching for a purpose and people who accept him Naruto joins the Infamous Ragnarock, thus leading to the birth of the Ninth Fist. The Next Great Adventure by ThatGuyYouKnew reviews Sick and tired of the magical world, Harry decides he needs a drastic change of scenery, and what's a more drastic change than an entirely new world?

On to the next great adventure! The ends ou la fin de tout T - French - Adventure - Chapters: Il en a marre de Dumbledore et ne lui permettra plus de conduire sa vie. Il s'entraine beaucoup et decouvre qui il est Post tome 5,Harry independant,puissant. T - French - Mystery - Chapters: Et si le Survivant venait de K - French - Chapters: T - French - Chapters: Il s'enfuit de Privet Drive.

Pour la suite venez voir. Sylphide, le retour xP Harry Potter - Rated: The repetitive, short sentences disconcertingly take the form of equations: The chasse-parties make visible the metaphoric substitution of money or commodities some of which happen to be human commodities for the body. The equation of human life with commercial value is endemic in the world described in narratives of piracy. Adventurers seize not only bullion but also prisoners, who are later transformed into monetary riches in the form of ransom. They attack slave ships and convert their human cargo into cash at illegal or corrupt versions of the sanctioned, regulated slave markets.

Money ensures the kind of esteem and dignity formerly conferred on heroes who displayed conventional forms of honor and valor. Commodities such as chocolate and sugar, for example, altered the everyday habits and appetites of elite French subjects. In her recent book, Trading Places: She interprets the relative absence of literary representations of the Antilles as indicative of a cultural desire to forget the abusive economic structures i. The minor genre of Caribbean adventure tales may represent one textual space in which French readers did directly confront unsettling questions about the human costs of the material riches produced in the island colonies.

They may be liberated from state oversight, these narratives suggest, but they are bound by their own greed. In this way, adventure narratives complemented contemporary moral and economic discourses that questioned the role of the profit motive in civilized society. Specters of the Atlantic: Finance, Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History. Duke University Press, The Compass of Society: Commerce and Absolutism in Old-Regime France. The Novel and the Sea. Princeton University Press, Cartes, tableaux, chronologies, bibliographies Ed. Histoire des aventuriers flibustiers. University of Pennsylvania Press, Creolization in the Early French Caribbean.

Gomberville, Marin le Roy sieur de. Belin-Leprieur et Plon, — Yale University Press, The Phantom of Chance: Edinburgh University Press, Rakes, Highwaymen, and Pirates: Johns Hopkins University Press, The French Atlantic Triangle: Literature and Culture of the Slave Trade. University of Minnesota Press, [original ].

Pirates, corsaires et flibustiers , eds. The Age of Chance: Gambling in Western Culture. Cambridge University Press, Villiers, Patrick and Jean-Pierre Duteil. This comparative approach allows her to note that the few texts to portray Atlantic piracy in the second half of the seventeenth century pale in comparison to the large number of early seventeenth-century texts to feature Mediterranean pirates. The text of the Code Michaud may be found in Isambert Patrick Villiers and Jean-Pierre Duteil write that, although by there was a clear distinction between corsaires contracted by states for the protection of their ships and outlaw pirates in the Mediterranean, no such clarity existed in the Antilles: The young couple runs away to sea together but is shipwrecked during a battle with pirates.

Leonor dies when a shark bites her leg off. Sent to Europe for his education, he takes up with bad company, seduces a girl, and is forced to escape to Brazil, passing through Africa en route. He falls in with English pirates, then French ones, with whom he seduces more women. He eventually flees to the Mediterranean, where his adventures with corsaires affect a peace treaty between France and Algiers. However, the only way to grasp fully the extravagance of these stories is to read them. The novella even includes recipes for potatoes with pimento sauce and turtle with broad beans and peas in herbs See Grussi for a more detailed account of the history of aristocratic gambling in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France specifically.

In his work on eighteenth-century literary aventuriers , Alexandre Stroev includes travelers and wanderers who search relentlessly for a better way of life. He argues that these figures reflect larger social fears, fantasies, and desires 3. The distinction between slavery and servitude was of utmost importance in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century legal theory.

Not surprisingly, then, the pirates in adventure narratives frequently target slave ships. See Serge Daget for an account of the intersections of piracy and the institutional slave trade in the early modern Caribbean. Printable PDF of Rousseau, — Les vaines justifications paraissent alors dissonantes et parasitaires. Presses universitaires de Rennes, Hannon, Patricia, Fabulous Identities: Women Writers and the History of the Fairy Tale. Lemoine, Patrick, La Fontaine les animaux et nous. Murat,Madame de, Contes, ed.

Perrault, Charles et al. Contes merveilleux , ed. Pinon, Laurent, Livres de zoologie de la Renaissance une anthologie — Editions Universitaires de Dijon, Tucker, Holly, Pregnant Fictions: Wayne State University Press, Ce n'est pas un Roi, ce n'est qu'un Roitelet. Le titre mentionne toujours sauf exception: Mirrors deceive and mirrors reveal.

Mirrors are ephemeral, just like beauty. The tale concludes with a magical transformation in the desert from monkey to beautiful woman—after which she marries her cousin, the prince, who once rejected her apish love, but eagerly accepts her now human hand. Babiole reunites with her birth mother, and they live happily ever after, free from bestial tones of the simian. Aspects of seeing, seeing oneself, and being seen are salient when considering this simian fairy tale.

Imitation, linked with ugliness, refinement, and beauty, becomes a site of stigma: The post-colonial perspective will be important for my reading of this tale, and a surprising juxtaposition of two mirror scenes later in the article will take this into consideration.

Self-reflexivity again plays a major role in collecting and cabinets of curiosity during this time period: In this frontispiece, we see an older woman, dressed as a sibyl, with glasses, holding a book. Two standing children—a girl and a boy—accompany her. On the floor in front of her is a cherubic child playing with a monkey on a leash. Jones, on the other hand, highlights how the monkey is tied to the theme of imitation: Jones also reads this sign of imitation as signaling that the literary conteuses of the era used parody: While I agree that imitation is clearly at stake, what interests me here is the mirror-like image the monkey and child represent; and like Jones, I am fascinated by the allusion to man and God.

The monkey is clearly seen as inferior and degenerate to the human, while man is seen as the inferior image of God; this hierarchical chain, with man being the monkey of God, is, in itself, a clever parody. Also we must not forget that monkeys were clearly connected to Satan, as he was also the ape of God Janson 17— Already, we see an emphasis on vision and beauty: And indeed, this superlative beauty of the human infant is rapidly followed by a dramatic change that is quite disturbing.

First, this concerning and horrifying conduct by the metamorphosed guenon incites gasps and cries of horror from the female courtesans. The queen is the most horrified of all. Here the aristocratic women lose their polished exteriors and become unrefined, primal, and emotive. However, in this case, the queen had a taste of initial, human beauty and then was immediately robbed of her pride and happiness. The worst thing imaginable happened—a beastly transformation—perhaps even more appalling than the death of a child.

In what follows, we shall see how several important terms and ideas are at work in the preceding passage. Was she always already a monkey, even her spirit, as this passage seems to imply? On appelle aussi guenon , une femme vieille ou laide, quand on luy veut dire quelque injure. The term was used to lambaste and castigate the feminine, but also implies a narrative of ownership and possession connected to plaisir.

The atmosphere of female domestic and aristocratic space is permeated with ugliness and misfortune. Here we will examine sight, mirroring, and breastfeeding. It is interesting to consider that vision is an integral part of the mother-infant relationship, or at least the wet nurse-infant relationship. Mirroring becomes paramount in this tale, and we see ugliness and monstrosity converge at this point.

This mirroring of the maternal face is remarkable and a hallmark of the mother-infant pair, and the queen is cheated of this special relationship. The mirroring relationship is foiled by the beastly transformation. This self-reflexive despair does not involve her child: How will this shameful and ugly event play out for the queen herself in relation to her subjects? Third, in this human-to-animal transformation of this dramatic scene, we witness one of the worst nightmares of a woman of this period: The child-beast who carries the curse of his or her mother—whether the mother thought about monkeys too much implying a narrative of mental illness, obsession, or impure thoughts , or whether a fairy cursed her—was indeed a monstrous sign.

The little prince wants to keep the monkey as a pet. She becomes a royal toy, a strange object of interrogation, and even an uncanny spectacle. The little prince demands that:. Babiole is dressed as a princess, but she clearly does not have a truly royal body: Cultural grooming is paramount in this passage.

She is dressed as a royal body and taught to behave and carry herself as a human, but then, in the next sentence, she becomes the most beautiful and charming guenon in the world, which seems to be in direct opposition to the aforementioned idea of ugliness and to the term guenon , although the idea of possession emerges front and center.

A narrative of race inserts itself here: This explicit blackness is an important signal, embedded in a narrative of animality, much in the same fashion that the colonized body was treated in the same manner as the animal—purchased, collected, displayed, and used. Babiole, much like the colonized, is imprisoned deeply within her animalized body. She then immediately strives to juxtapose this bestiality with a description of how full of vivacity and energy Babiole is. These two conflicting aspects of her character trouble the reader, forcing the reader to examine her own relationship to the bestial and the refined.

In opposition to her mother, her aunt and her young cousin exhibit her. This description recalls naturalist texts: Thus Babiole, the monkey princess, is not so repellent to her aunt or her cousin, the prince: She is no longer the product of a monstrous birth; her value rests in her difference in a society that esteems collections and oddities. The objectification and display of her body continues: She is empathetic; when the prince cries, she does also.

Cartesian philosophy was not foreign to the conteuses: He also writes that they resemble and imitate man, but that they are indeed not human — Babiole is constantly grappling with bestial, violent feelings: Here we see a perverse cycle of refinement unfolding. Moroever, to be refined, one must collect, and one must participate in the circulation and exchange of bibelots of the period. Cultivation and refinement are something to work towards, and they are not completely inherent to the soul—human or animal.

She is a wondrous spectacle, so very human, but not quite. The zenith of her refinement is, however, represented by the fact that Babiole falls in love with her cousin, the prince. In the case of Babiole, she pathologizes the pain of her non-reciprocal love for the prince.

When she confesses her love for the prince, he laughs This animal-human tension, and the subsequent repulsion Babiole feels, manifests itself by a refusal to look in the mirror. Babiole is all too conscious of her curse. During this time, mirrors underlined beauty, finery and physical perfection. This scene of Babiole and her mirror tells the tale of a despised relationship with the mirror image.

Ugliness and self-loathing is paramount in this episode. In fact, the only time that Babiole looks into a mirror, she wishes to shatter it. Moreover, an emphasis on the fracturing of the image, or the animal self, is central to this portion of the text. Very similar themes are played out in an early nineteenth-century novel. Ourika chronicles the life of a young Senegalese woman torn from her native land, enslaved, and consequently raised by a French family during the revolution. From the age of two onward, the aristocratic family that raises her with their son, Charles, culturally grooms her.

In the case of Babiole, her bestial body prevents their union; in the case of Ourika, it is her black body that forbids her to love and be loved. Although the two are separated by more than a hundred years, the connection between the black body and the simian is evident. The other, whether animal or the colonized, is cast outside of the realm of true beauty.

In the end, Babiole is transformed into a human female and seems to achieve true refinement and beauty according to period ideals; in the case of Ourika, Charles chooses to marry another, and this devastating news devours Ourika, who dies from a broken heart in a convent, without her aristocratic family. These scenes convey the fear of the other, the anxiety of incivility and unrefinement that is equated with ugliness and the bestial. Babiole is stripped of agency. Thus the unsettled nature of imitation culminates at this point in the fairy tale. It is interesting to consider the ambassador-parrot who delivers a message from the monkey king, Magot, to the object of his kingly desire, Babiole.

A human being would have realized that cleanliness had been achieved and ceased, due to higher cognitive abilities: He is not full of spirit and vivacity, as Babiole is. One imitates, but does so carefully and with prudence: Imitation of the refined and the beautiful is evoked as powerful in this fairy tale.

It is her physical refinement that saves Babiole. Again, the mirror becomes integral to seeing and being seen: In addition to this violent rhetoric, the simian is clearly connected to the other, non-white body. However, Babiole claims that she is cultivated and witty: The struggle between the beastly and the refined and its connection to beauty persists. The queen asks if Babiole is capable of tenderness, because, in the end, she is a beast, even if she is capable of speaking. At last, the queen realizes that Babiole is her daughter and she tries to sequester Babiole in a castle, for this time she feels that she cannot kill her own flesh and blood; she has so much spirit, this Babiole, and it is too bad that the child is just not natural Babiole is a contaminated mirror of her mother, and her female relatives in general, and an unsavory reminder of a tormented past inflicted by an evil fairy.

Babiole carries the physical sign of savagery and unrefinement, yet she is also intellectually refined. The queen as well as readers of the conte would interpret her as a dangerous and uncontrollable hybrid package of civility against incivility. It is only at the end of the tale, and only after the transformation of Babiole into a woman, that the prince and her mother finally accept her. Yet this freedom from the bestial is complicated indeed. King Magot and his gifts initiate her transformation from monkey to human. Earlier in the fairy tale, he gave Babiole a glass chest with an olive and a hazelnut This is an extreme change from the previous desire to break a mirror when looking at her reflection as a monkey.

Now she has an urgent desire to look at herself as a beautiful woman. But her beauty as a woman is not typical—it is superlative. The opposition between ugliness and refinement operates clearly here. Again, we come back to these binaries of ugliness and refinement, and ugliness and beauty: The ugly and the bestial are decidedly conflated in this tale. Beauty of the soul and of the spirit is held in higher esteem than physical beauty. In the case of Babiole, her animality limits her to the bestial realm.

Et qui pourtant des plus grands hommes. Mais il faudroit en leur faveur,. Que quelque enchanteur charitable. The monkey is a figure conflated with evil, curses, ugliness, and women—but the monkey also reflects an aspect of sublimated humanity. The monkey allows us to see ourselves: Daston, Lorraine and Katharine Park. Who would not seek to make them known to others, that they too may enjoy, and render thanks? His style in particular — using the word in its widest sense — forms the subject of the principal part of Mr. Before, however, discussing this, the true crux of the question, it may be well to consider briefly another matter which deserves attention, because the English reader is apt to find in it a stumbling-block at the very outset of his inquiry.

Coming to Racine with Shakespeare and the rest of the Elizabethans warm in his memory, it is only to be expected that he should be struck with a chilling sense of emptiness and unreality. For what is the principle which underlies and justifies the unities of time and place? Surely it is not, as Mr. Very different were the views of the Elizabethan tragedians, who aimed at representing not only the catastrophe, but the whole development of circumstances of which it was the effect; they traced, with elaborate and abounding detail, the rise, the growth, the decline, and the ruin of great causes and great persons; and the result was a series of masterpieces unparalleled in the literature of the world.

But, for good or evil, these methods have become obsolete, and to-day our drama seems to be developing along totally different lines. Thus, from the point of view of form, it is true to say that it has been the drama of Racine rather than that of Shakespeare that has survived. Plays of the type of Macbeth have been superseded by plays of the type of Britannicus. Britannicus , no less than Macbeth , is the tragedy of a criminal; but it shows us, instead of the gradual history of the temptation and the fall, followed by the fatal march of consequences, nothing but the precise psychological moment in which the first irrevocable step is taken, and the criminal is made.

The method of Macbeth has been, as it were, absorbed by that of the modern novel; the method of Britannicus still rules the stage. But Racine carried out his ideals more rigorously and more boldly than any of his successors. His dramas must be read as one looks at an airy, delicate statue, supported by artificial props, whose only importance lies in the fact that without them the statue itself would break in pieces and fall to the ground.

It is remarkable that Mr. But it is a little difficult to make certain of the precise nature of Mr. The truth is that we have struck here upon a principle which lies at the root, not only of Mr. How often this method has been employed, and how often it has proved disastrously fallacious! For, after all, art is not a superior kind of chemistry, amenable to the rules of scientific induction. Its component parts cannot be classified and tested, and there is a spark within it which defies foreknowledge.

When Matthew Arnold declared that the value of a new poem might be gauged by comparing it with the greatest passages in the acknowledged masterpieces of literature, he was falling into this very error; for who could tell that the poem in question was not itself a masterpiece, living by the light of an unknown beauty, and a law unto itself? It is the business of the poet to break rules and to baffle expectation; and all the masterpieces in the world cannot make a precedent.

There is only one way to judge a poet, as Wordsworth, with that paradoxical sobriety so characteristic of him, has pointed out — and that is, by loving him. Bailey, with regard to Racine at any rate, has not followed the advice of Wordsworth. Let us look a little more closely into the nature of his attack.

And doubtless most English readers would be inclined to agree with Mr. Bailey, for it so happens that our own literature is one in which rarity of style, pushed often to the verge of extravagance, reigns supreme. Owing mainly, no doubt, to the double origin of our language, with its strange and violent contrasts between the highly-coloured crudity of the Saxon words and the ambiguous splendour of the Latin vocabulary; owing partly, perhaps, to a national taste for the intensely imaginative, and partly, too, to the vast and penetrating influence of those grand masters of bizarrerie — the Hebrew Prophets — our poetry, our prose, and our whole conception of the art of writing have fallen under the dominion of the emphatic, the extraordinary, and the bold.

No one in his senses would regret this, for it has given our literature all its most characteristic glories, and, of course, in Shakespeare, with whom expression is stretched to the bursting point, the national style finds at once its consummate example and its final justification. But the result is that we have grown so unused to other kinds of poetical beauty, that we have now come to believe, with Mr.

The beauties of restraint, of clarity, of refinement, and of precision we pass by unheeding; we can see nothing there but coldness and uniformity; and we go back with eagerness to the fling and the bravado that we love so well. It is as if we had become so accustomed to looking at boxers, wrestlers, and gladiators that the sight of an exquisite minuet produced no effect on us; the ordered dance strikes us as a monotony, for we are blind to the subtle delicacies of the dancers, which are fraught with such significance to the practised eye. But let us be patient, and let us look again.

But is there not an enchantment? Is there not a vision? Is there not a flow of lovely sound whose beauty grows upon the ear, and dwells exquisitely within the memory? The narrowness of his vocabulary is in fact nothing but a proof of his amazing art. In the following passage, for instance, what a sense of dignity and melancholy and power is conveyed by the commonest words! Never, surely, before or since, was a simple numeral put to such a use — to conjure up so triumphantly such mysterious grandeurs!

But these are subtleties which pass unnoticed by those who have been accustomed to the violent appeals of the great romantic poets. As Sainte—Beuve says, in a fine comparison between Racine and Shakespeare, to come to the one after the other is like passing to a portrait by Ingres from a decoration by Rubens. Who will match them among the formal elegances of Racine? His daring is of a different kind; it is not the daring of adventure but of intensity; his fine surprises are seized out of the very heart of his subject, and seized in a single stroke. Thus many of his most astonishing phrases burn with an inward concentration of energy, which, difficult at first to realise to the full, comes in the end to impress itself ineffaceably upon the mind.

The sentence is like a cavern whose mouth a careless traveller might pass by, but which opens out, to the true explorer, into vista after vista of strange recesses rich with inexhaustible gold. But what is it that makes the English reader fail to recognise the beauty and the power of such passages as these? The great majority of poets — and especially of English poets — produce their most potent effects by the accumulation of details — details which in themselves fascinate us either by their beauty or their curiosity or their supreme appropriateness.

But with details Racine will have nothing to do; he builds up his poetry out of words which are not only absolutely simple but extremely general, so that our minds, failing to find in it the peculiar delights to which we have been accustomed, fall into the error of rejecting it altogether as devoid of significance. And the error is a grave one, for in truth nothing is more marvellous than the magic with which Racine can conjure up out of a few expressions of the vaguest import a sense of complete and intimate reality.

And Virgil adds touch upon touch of exquisite minutiae:. What a flat and feeble set of expressions! He might have written every page of his work without so much as looking out of the window of his study. But he is constantly, with his subtle art, suggesting them. In this line, for instance, he calls up, without a word of definite description, the vision of a sudden and brilliant sunrise:. And how varied and beautiful are his impressions of the sea!

He can give us the desolation of a calm:. And then, in a single line, he can evoke the radiant spectacle of a triumphant flotilla riding the dancing waves:. But it is not only suggestions of nature that readers like Mr. Bailey are unable to find in Racine — they miss in him no less suggestions of the mysterious and the infinite.

No doubt this is partly due to our English habit of associating these qualities with expressions which are complex and unfamiliar. But there is another reason — the craving, which has seized upon our poetry and our criticism ever since the triumph of Wordsworth and Coleridge at the beginning of the last century, for metaphysical stimulants.

But Milton is sacrosanct in England; no theory, however mistaken, can shake that stupendous name, and the damage which may be wrought by a vicious system of criticism only becomes evident in its treatment of writers like Racine, whom it can attack with impunity and apparent success. But if, instead of asking what a writer is without, we try to discover simply what he is, will not our results be more worthy of our trouble?

And in fact, if we once put out of our heads our longings for the mystery of metaphysical suggestion, the more we examine Racine, the more clearly we shall discern in him another kind of mystery, whose presence may eventually console us for the loss of the first — the mystery of the mind of man. Look where we will, we shall find among his pages the traces of an inward mystery and the obscure infinities of the heart. The line is a summary of the romance and the anguish of two lives. This last line — written, let us remember, by a frigidly ingenious rhetorician, who had never looked out of his study-window — does it not seem to mingle, in a trance of absolute simplicity, the peerless beauty of a Claude with the misery and ruin of a great soul?

It is, perhaps, as a psychologist that Racine has achieved his most remarkable triumphs; and the fact that so subtle and penetrating a critic as M. On the contrary, his admirers are now tending more and more to lay stress upon the brilliance of his portraits, the combined vigour and intimacy of his painting, his amazing knowledge, and his unerring fidelity to truth.

- 664 commentaires.

- Abnehmen ohne Kohlenhydrate: 199 Lebensmittel ohne Kohlenhydrate (Low Carb) (German Edition).

- Loss is Part of Life (Little Book Series of Emotional Health For Emotional Wealth 13)!

These are vague phrases, no doubt, but they imply a very definite point of view; and it is curious to compare with it our English conception of Racine as a stiff and pompous kind of dancing-master, utterly out of date and infinitely cold. And there is a similar disagreement over his style. When Racine is most himself, when he is seizing upon a state of mind and depicting it with all its twistings and vibrations, he writes with a directness which is indeed naked, and his sentences, refined to the utmost point of significance, flash out like swords, stroke upon stroke, swift, certain, irresistible.

This is how Agrippine, in the fury of her tottering ambition, bursts out to Burrhus, the tutor of her son:. When we come upon a passage like this we know, so to speak, that the hunt is up and the whole field tearing after the quarry. But Racine, on other occasions, has another way of writing. He can be roundabout, artificial, and vague; he can involve a simple statement in a mist of high-sounding words and elaborate inversions. But there is a meaning in it, after all. Every art is based upon a selection, and the art of Racine selected the things of the spirit for the material of its work.

The things of sense — physical objects and details, and all the necessary but insignificant facts that go to make up the machinery of existence — these must be kept out of the picture at all hazards. To have called a spade a spade would have ruined the whole effect; spades must never be mentioned, or, at the worst, they must be dimly referred to as agricultural implements, so that the entire attention may be fixed upon the central and dominating features of the composition — the spiritual states of the characters — which, laid bare with uncompromising force and supreme precision, may thus indelibly imprint themselves upon the mind.

To condemn Racine on the score of his ambiguities and his pomposities is to complain of the hastily dashed-in column and curtain in the background of a portrait, and not to mention the face. Sometimes indeed his art seems to rise superior to its own conditions, endowing even the dross and refuse of what it works in with a wonderful significance. To have called a bowstring a bowstring was out of the question; and Racine, with triumphant art, has managed to introduce the periphrasis in such a way that it exactly expresses the state of mind of the Sultana.

She begins with revenge and rage, until she reaches the extremity of virulent resolution; and then her mind begins to waver, and she finally orders the execution of the man she loves, in a contorted agony of speech. Very different is the Shakespearean method. There, as passion rises, expression becomes more and more poetical and vague. Image flows into image, thought into thought, until at last the state of mind is revealed, inform and molten, driving darkly through a vast storm of words.

Such revelations, no doubt, come closer to reality than the poignant epigrams of Racine. One might be tempted to say that his art represents the sublimed essence of reality, save that, after all, reality has no degrees. It would be nearer the truth to rank Racine among the idealists. Upon English ears the rhymed couplets of Racine sound strangely; and how many besides Mr. But to his lovers, to those who have found their way into the secret places of his art, his lines are impregnated with a peculiar beauty, and the last perfection of style.

And, as to his rhymes, they seem perhaps, to the true worshipper, the final crown of his art. Bailey tells us that the couplet is only fit for satire. Has he forgotten Lamia? But Dryden himself has spoken memorably upon rhyme. You see there the united design of many persons to make up one figure;. For Racine, with his prepossessions of sublimity and perfection, some such barrier between his universe and reality was involved in the very nature of his art. He has affinities with many; but likenesses to few. In a sense we can know him in our library, just as we can hear the music of Mozart with silent eyes.

But, when the strings begin, when the whole volume of that divine harmony engulfs us, how differently then we understand and feel! And so, at the theatre, before one of those high tragedies, whose interpretation has taxed to the utmost ten generations of the greatest actresses of France, we realise, with the shock of a new emotion, what we had but half-felt before. The life of Sir Thomas Browne does not afford much scope for the biographer.

It is obvious that, with such scanty and unexciting materials, no biographer can say very much about what Sir Thomas Browne did; it is quite easy, however, to expatiate about what he wrote. He dug deeply into so many subjects, he touched lightly upon so many more, that his works offer innumerable openings for those half-conversational digressions and excursions of which perhaps the pleasantest kind of criticism is composed. It would be rash indeed to attempt to improve upon Mr.

Gosse, who has so much to say on such a variety of topics, has unfortunately limited to a very small number of pages his considerations upon what is, after all, the most important thing about the author of Urn Burial and The Garden of Cyrus — his style. Gosse himself confesses that it is chiefly as a master of literary form that Browne deserves to be remembered. Why then does he tell us so little about his literary form, and so much about his family, and his religion, and his scientific opinions, and his porridge, and who fished up the murex? Nor is it only owing to its inadequacy that Mr.

Gosse has for once been deserted by his sympathy and his acumen. Gosse cannot help protesting somewhat acrimoniously against that very method of writing whose effects he is so ready to admire. In practice, he approves; in theory, he condemns. He ranks the Hydriotaphia among the gems of English literature; and the prose style of which it is the consummate expression he denounces as fundamentally wrong. The contradiction is obvious; but there can be little doubt that, though Browne has, as it were, extorted a personal homage, Mr. The study of Sir Thomas Browne, Mr.

The characteristics of the pre-Johnsonian prose style — the style which Dryden first established and Swift brought to perfection — are obvious enough. Its advantages are those of clarity and force; but its faults, which, of course, are unimportant in the work of a great master, become glaring in that of the second-rate practitioner. The prose of Locke, for instance, or of Bishop Butler, suffers, in spite of its clarity and vigour, from grave defects. It is very flat and very loose; it has no formal beauty, no elegance, no balance, no trace of the deliberation of art.

Johnson, there can be no doubt, determined to remedy these evils by giving a new mould to the texture of English prose; and he went back for a model to Sir Thomas Browne. Gosse himself observes, Browne stands out in a remarkable way from among the great mass of his contemporaries and predecessors, by virtue of his highly developed artistic consciousness.

He was, says Mr.

Émile, ou De l’éducation/Édition /Livre IV - Wikisource

With the Christian Morals to guide him, Dr. Johnson set about the transformation of the prose of his time. He decorated, he pruned, he balanced; he hung garlands, he draped robes; and he ended by converting the Doric order of Swift into the Corinthian order of Gibbon. It is, indeed, a curious reflection, but one which is amply justified by the facts, that the Decline and Fall could not have been precisely what it is, had Sir Thomas Browne never written the Christian Morals.

That Johnson and his disciples had no inkling of the inner spirit of the writer to whose outward form they owed so much, has been pointed out by Mr. His view seems to be, in fact, the precise antithesis of Dr. The truth is, that there is a great gulf fixed between those who naturally dislike the ornate, and those who naturally love it. There is no remedy; and to attempt to ignore this fact only emphasises it the more. The critic who admits the jar, but continues to appreciate, must present, to the true enthusiast, a spectacle of curious self-contradiction. If once the ornate style be allowed as a legitimate form of art, no attack such as Mr.

For it is surely an error to judge and to condemn the latinisms without reference to the whole style of which they form a necessary part. A very little reflection and inquiry will suffice to show how completely mistaken this view really is. The truth is clear enough. He did not choose his words according to rule, but according to the effect which he wished them to have. Thus, when he wished to suggest an extreme contrast between simplicity and pomp, we find him using Saxon words in direct antithesis to classical ones.

The reason is not far to seek. In his most characteristic moments he was almost entirely occupied with thoughts and emotions which can, owing to their very nature, only be expressed in Latinistic language. The state of mind which he wished to produce in his readers was nearly always a complicated one: Let intellectual tubes give thee a glance of things which visive organs reach not. Have a glimpse of incomprehensibles; and thoughts of things, which thoughts but tenderly touch.

Not only is the Saxon form of speech devoid of splendour and suggestiveness; its simplicity is still further emphasised by a spondaic rhythm which seems to produce by some mysterious rhythmic law an atmosphere of ordinary life, where, though the pathetic may be present, there is no place for the complex or the remote.

To understand how unsuitable such conditions would be for the highly subtle and rarefied art of Sir Thomas Browne, it is only necessary to compare one of his periods with a typical passage of Saxon prose. To whom Master Latimer spake in this manner: Nothing could be better adapted to the meaning and sentiment of this passage than the limpid, even flow of its rhythm. But who could conceive of such a rhythm being ever applicable to the meaning and sentiment of these sentences from the Hydriotaphia?

To extend our memories by monuments, whose death we daily pray for, and whose duration we cannot hope without injury to our expectations in the advent of the last day, were a contradiction to our beliefs. Here the long, rolling, almost turgid clauses, with their enormous Latin substantives, seem to carry the reader forward through an immense succession of ages, until at last, with a sudden change of the rhythm, the whole of recorded time crumbles and vanishes before his eyes. The entire effect depends upon the employment of a rhythmical complexity and subtlety which is utterly alien to Saxon prose.

It would be foolish to claim a superiority for either of the two styles; it would be still more foolish to suppose that the effects of one might be produced by means of the other. Wealth of rhythmical elaboration was not the only benefit which a highly Latinised vocabulary conferred on Browne.

Without it, he would never have been able to achieve those splendid strokes of stylistic bravura , which were evidently so dear to his nature, and occur so constantly in his finest passages. The precise quality cannot be easily described, but is impossible to mistake; and the pleasure which it produces seems to be curiously analogous to that given by a piece of magnificent brushwork in a Rubens or a Velasquez. It is then that one begins to understand how mistaken it was of Sir Thomas Browne not to have written in simple, short, straightforward Saxon English. Certain classical words, partly owing to their allusiveness, partly owing to their sound, possess a remarkable flavour which is totally absent from those of Saxon derivation.

Gosse has flown to the opposite extreme, and will not allow Browne any sense of humour at all. The confusion no doubt arises merely from a difference in the point of view. The Early Victorians, however, missed the broad outlines, and were altogether taken up with the obvious grotesqueness of the details.

Comic strips

Browne, like an impressionist painter, produced his pictures by means of a multitude of details which, if one looks at them in themselves, are discordant, and extraordinary, and even absurd. There can be little doubt that this strongly marked taste for curious details was one of the symptoms of the scientific bent of his mind. For Browne was scientific just up to the point where the examination of detail ends, and its coordination begins. He knew little or nothing of general laws; but his interest in isolated phenomena was intense.

And the more singular the phenomena, the more he was attracted. He was always ready to begin some strange inquiry. He cannot help wondering: Browne, however, used his love of details for another purpose: His method was one which, to be successful, demanded a self-confidence, an imagination, and a technical power, possessed by only the very greatest artists.

Les damnés de la route - Tome 10 - Sortie de route pour la deuche !

His success gives him a place beside Webster and Blake, on one of the very highest peaks of Parnassus. The road skirts the precipice the whole way. If one fails in the style of Pascal, one is merely flat; if one fails in the style of Browne, one is ridiculous. He who plays with the void, who dallies with eternity, who leaps from star to star, is in danger at every moment of being swept into utter limbo, and tossed forever in the Paradise of Fools.

Browne produced his greatest work late in life; for there is nothing in the Religio Medici which reaches the same level of excellence as the last paragraphs of The Garden of Cyrus and the last chapter of Urn Burial. A long and calm experience of life seems, indeed, to be the background from which his most amazing sentences start out into being. His strangest phantasies are rich with the spoils of the real world. His art matured with himself; and who but the most expert of artists could have produced this perfect sentence in The Garden of Cyrus , so well known, and yet so impossible not to quote?

Nor will the sweetest delight of gardens afford much comfort in sleep; wherein the dullness of that sense shakes hands with delectable odours; and though in the bed of Cleopatra, can hardly with any delight raise up the ghost of a rose. This is Browne in his most exquisite mood. To crown all, he has scattered through these few pages a multitude of proper names, most of them gorgeous in sound, and each of them carrying its own strange freight of reminiscences and allusions from the unknown depths of the past.

Among them, one visionary figure flits with a mysterious pre-eminence, flickering over every page, like a familiar and ghostly flame. But it would be vain to dwell further upon this wonderful and famous chapter, except to note the extraordinary sublimity and serenity of its general tone. Browne never states in so many words what his own feelings towards the universe actually are. He speaks of everything but that; and yet, with triumphant art, he manages to convey into our minds an indelible impression of the vast and comprehensive grandeur of his soul. It is interesting — or at least amusing — to consider what are the most appropriate places in which different authors should be read.

Pope is doubtless at his best in the midst of a formal garden, Herrick in an orchard, and Shelley in a boat at sea.

- Émile, ou De l’éducation/Édition 1852/Livre IV;

- Thoughts for the Holidays: Finding Permission to Grieve.

- top 10 most popular citroen cv brands.

- Download ↠ L'Affaire PDF by ↠ Jean-Denis Bredin eBook or Kindle ePUB free;

- Site Sections?

- Dateline: Toronto: The Complete Toronto Star Dispatches, 1920-1924!

- Bloc-notes : la gauche sectaire fait fuir les intellectuels!

Sir Thomas Browne demands, perhaps, a more exotic atmosphere. One could read him floating down the Euphrates, or past the shores of Arabia; and it would be pleasant to open the Vulgar Errors in Constantinople, or to get by heart a chapter of the Christian Morals between the paws of a Sphinx. In England, the most fitting background for his strange ornament must surely be some habitation consecrated to learning, some University which still smells of antiquity and has learnt the habit of repose. But, after all, who can doubt that it is at Oxford that Browne himself would choose to linger?

May we not guess that he breathed in there, in his boyhood, some part of that mysterious and charming spirit which pervades his words? For one traces something of him, often enough, in the old gardens, and down the hidden streets; one has heard his footstep beside the quiet waters of Magdalen; and his smile still hovers amid that strange company of faces which guard, with such a large passivity, the circumference of the Sheldonian.

The whole of the modern criticism of Shakespeare has been fundamentally affected by one important fact. The establishment of metrical tests, by which the approximate position and date of any play can be readily ascertained, at once followed; chaos gave way to order; and, for the first time, critics became able to judge, not only of the individual works, but of the whole succession of the works of Shakespeare.

Upon this firm foundation modern writers have been only too eager to build. It was apparent that the Plays, arranged in chronological order, showed something more than a mere development in the technique of verse — a development, that is to say, in the general treatment of characters and subjects, and in the sort of feelings which those characters and subjects were intended to arouse; and from this it was easy to draw conclusions as to the development of the mind of Shakespeare itself.

Such conclusions have, in fact, been constantly drawn. But it must be noted that they all rest upon the tacit assumption, that the character of any given drama is, in fact, a true index to the state of mind of the dramatist composing it. The validity of this assumption has never been proved; it has never been shown, for instance, why we should suppose a writer of farces to be habitually merry; or whether we are really justified in concluding, from the fact that Shakespeare wrote nothing but tragedies for six years, that, during that period, more than at any other, he was deeply absorbed in the awful problems of human existence.

It is not, however, the purpose of this essay to consider the question of what are the relations between the artist and his art; for it will assume the truth of the generally accepted view, that the character of the one can be inferred from that of the other. Such, in fact, is the general opinion of modern writers upon Shakespeare; after a happy youth and a gloomy middle age he reached at last — it is the universal opinion — a state of quiet serenity in which he died.

Ten Brink, by Sir I. Gollancz, and, to a great extent, by Dr. That he did eventually attain to a state of calm content, that he did, in fact, die happy — it is this that gives colour and interest to the whole theory. One other complete play, however, and one other fragment, do resemble in some degree these works of the final period; for, immediately preceding them in date, they show clear traces of the beginnings of the new method, and they are themselves curiously different from the plays they immediately succeed — that great series of tragedies which began with Hamlet in and ended in with Antony and Cleopatra.

For six years he had been persistently occupied with a kind of writing which he had himself not only invented but brought to the highest point of excellence — the tragedy of character. Every one of his masterpieces has for its theme the action of tragic situation upon character; and, without those stupendous creations in character, his greatest tragedies would obviously have lost the precise thing that has made them what they are.

Yet, after Antony and Cleopatra Shakespeare deliberately turned his back upon the dramatic methods of all his past career. There seems no reason why he should not have continued, year after year, to produce Othellos, Hamlets , and Macbeths ; instead, he turned over a new leaf, and wrote Coriolanus. Coriolanus is certainly a remarkable, and perhaps an intolerable play: But it pleased him to ignore completely all these opportunities; and, in the play he has given us, the situations, mutilated and degraded, serve merely as miserable props for the gorgeous clothing of his rhetoric.

For rhetoric, enormously magnificent and extraordinarily elaborate, is the beginning and the middle and the end of Coriolanus. The vigour of the presentment is, it is true, amazing; but it is a presentment of decoration, not of life. So far and so quickly had Shakespeare already wandered from the subtleties of Cleopatra. The transformation is indeed astonishing; one wonders, as one beholds it, what will happen next. At about the same time, some of the scenes in Timon of Athens were in all probability composed: For sheer virulence of foul-mouthed abuse, some of the speeches in Timon are probably unsurpassed in any literature; an outraged drayman would speak so, if draymen were in the habit of talking poetry.

From this whirlwind of furious ejaculation, this splendid storm of nastiness, Shakespeare, we are confidently told, passed in a moment to tranquillity and joy, to blue skies, to young ladies, and to general forgiveness. From to [says Professor Dowden] a show of tragic figures, like the kings who passed before Macbeth, filled the vision of Shakespeare; until at last the desperate image of Timon rose before him; when, as though unable to endure or to conceive a more lamentable ruin of man, he turned for relief to the pastoral loves of Prince Florizel and Perdita; and as soon as the tone of his mind was restored, gave expression to its ultimate mood of grave serenity in The Tempest , and so ended.

This is a pretty picture, but is it true? Modern critics, in their eagerness to appraise everything that is beautiful and good at its proper value, seem to have entirely forgotten that there is another side to the medal; and they have omitted to point out that these plays contain a series of portraits of peculiar infamy, whose wickedness finds expression in language of extraordinary force. To omit these figures of discord and evil from our consideration, to banish them comfortably to the background of the stage, while Autolycus and Miranda dance before the footlights, is surely a fallacy in proportion; for the presentment of the one group of persons is every whit as distinct and vigorous as that of the other.

Iachimo tells us how:. But how has it happened that the judgment of so many critics has been so completely led astray? Charm and gravity, and even serenity, are to be found in many other plays of Shakespeare. For, in Measure for Measure Isabella is no whit less pure and lovely than any Perdita or Miranda, and her success is as complete; yet who would venture to deny that the atmosphere of Measure for Measure was more nearly one of despair than of serenity?

What is it, then, that makes the difference? Why should a happy ending seem in one case futile, and in another satisfactory? Why does it sometimes matter to us a great deal, and sometimes not at all, whether virtue is rewarded or not? The reason, in this case, is not far to seek.

The characters are real men and women; and what happens to them upon the stage has all the effect of what happens to real men and women in actual life. Their goodness appears to be real goodness, their wickedness real wickedness; and, if their sufferings are terrible enough, we regret the fact, even though in the end they triumph, just as we regret the real sufferings of our friends. But, in the plays of the final period, all this has changed; we are no longer in the real world, but in a world of enchantment, of mystery, of wonder, a world of shifting visions, a world of hopeless anachronisms, a world in which anything may happen next.

The pretences of reality are indeed usually preserved, but only the pretences. Cymbeline is supposed to be the king of a real Britain, and the real Augustus is supposed to demand tribute of him; but these are the reasons which his queen, in solemn audience with the Roman ambassador, urges to induce her husband to declare for war:. It comes with something of a shock to remember that this medley of poetry, bombast, and myth will eventually reach the ears of no other person than the Octavius of Antony and Cleopatra ; and the contrast is the more remarkable when one recalls the brilliant scene of negotiation and diplomacy in the latter play, which passes between Octavius, Maecenas, and Agrippa on the one side, and Antony and Enobarbus on the other, and results in the reconciliation of the rivals and the marriage of Antony and Octavia.

And of course, in this sort of fairy land, it is an essential condition that everything shall end well; the prince and princess are bound to marry and live happily ever afterwards, or the whole story is unnecessary and absurd; and the villains and the goblins must naturally repent and be forgiven.

But it is clear that such happy endings, such conventional closes to fantastic tales, cannot be taken as evidences of serene tranquillity on the part of their maker; they merely show that he knew, as well as anyone else, how such stories ought to end. Yet there can be no doubt that it is this combination of charming heroines and happy endings which has blinded the eyes of modern critics to everything else.