Alassane Ouattara : une ambition pour la Côte dIvoire (ESSAI ET DOC) (French Edition)

A youth not far from me took a gunshot straight to his head; it was as if part of his face was blown off. He was one of at least two killed that I saw with my own eyes. As the women reached where they had planned to assemble, a green pickup with a mounted machine gun, a police cargo truck, a green military camouflage tank, and a blue gendarme tank passed by.

Three witnesses told Human Rights Watch that the tank fired a heavy weapon. Almost simultaneously, someone in green fatigues with a military helmet opened fire with a machine gun mounted on the back of a pickup. More than a dozen Abobo residents described how security forces drove quickly through territory controlled by pro-Ouattara forces several times every day, firing Kalashnikovs in every direction—sometimes in the air, other times toward people on the streets.

The daily attacks ultimately led to the massive internal displacement of people from Abobo. The doctor was unable to clarify how many of the wounded were civilians. Human Rights Watch believes, based on interviews with witnesses and neighborhood residents, that the attackers were from the Invisible Commandos. Witnesses described the attackers descending upon Anonkoua from Abobo PK, which was the base of the Invisible Commandos from late February through late April.

On March 6, there had been combat in the area between Gbagbo forces and the Invisible Commandos. Victims of the March 7 attack as well as a fighter from the Invisible Commandos told Human Rights Watch that pro-Ouattara forces acted out of concern that weapons had been left in the village by pro-Gbagbo forces. One year-old victim told Human Rights Watch:. Another witness described watching pro-Ouattara forces slit the throat of his year-old father. Neighbors intervened on his behalf, which the victim believed saved his life, but the attackers stole all his possessions.

Human Rights Watch documented the summary execution of 11 armed forces and militia members loyal to Gbagbo between March 1 and In seven cases, witnesses described how pro-Ouattara forces stopped vehicles or individuals on foot at checkpoints in Abobo to search for weapons. One pro-Ouattara combatant in Abobo—who identified himself as part of the Invisible Commandos—described four cases to Human Rights Watch in which he had been part of this kind of operation.

On March 2, an ambulance was stopped and his fellow-combatants said they had discovered Kalashnikovs during the search; the driver was then detained. On March 5, the pro-Ouattara fighter said he found three people with arms passing a checkpoint on foot near the Abobo sub-neighborhood of Anonkoua. In both cases, the pro-Ouattara fighter said he brought the detainees to a higher-level commander, indicating organization and a clear chain of command. A witness to the execution of another three people believed to be loyal to Gbagbo told Human Rights Watch:.

In another incident on March 7, pro-Ouattara forces detained four alleged militia leaders in Abobo and summarily executed them. Credible accounts indicated that two people were captured and then used to lay a trap for higher-level leaders, before the pro-Ouattara forces executed all of them. His throat had been cut completely. In the video, another victim was seen to be impaled with a stake.

- ?

- Ep.#5 - Rise of the Corinari (The Frontiers Saga).

- .

- Côte d’Ivoire Post-Gbagbo: Crisis Recovery - www.newyorkethnicfood.com.

Although the first towns were captured at the end of February, intense fighting between armed forces began in mid-March in the far west and at the end of March in Abidjan. In the far west, retreating militia and mercenary groups loyal to Gbagbo perpetrated massacres and widespread killings as they inflicted a final wave of violence against northern Ivorians and West African immigrants. In Abidjan, security forces aligned with Gbagbo indiscriminately shelled civilian areas, launching heavy weapons into market places and neighborhoods.

Pro-Gbagbo militia groups launched attacks on homes and created frequent checkpoints, killing hundreds of perceived Ouattara supporters in horrifyingly brutal ways. In return, as the Republican Forces swept through the country, they left a trail of killings, rapes, and villages burned to the ground. In the far west, Ouattara-aligned forces executed elderly persons unable to flee the combat. After taking control of Abidjan, the Republican Forces executed at least people and tortured or treated inhumanely scores more in detention.

At a minimum, these constitute war crimes under international law. But given the widespread and, at times, organized nature of the acts, they likely also amount to crimes against humanity. As the Republican Forces advanced during their military offensive, regular armed forces previously loyal to Gbagbo retreated quickly.

Other pro-Gbagbo forces, however, notably Ivorian militiamen and Liberian mercenaries [see text box below], often stayed behind. Many of these forces appeared to take a final opportunity to commit atrocities against alleged Ouattara supporters before retreating as well. Others crossed with the promise of later payment as well as the express ability to loot. Witnesses described the militiamen, armed with automatic weapons, RPGs, and machetes, killing immigrants inside their homes and as they attempted to flee.

As the attackers left, they pillaged and in some instances burned houses, looting any item of value, including motorcycles, money, televisions, mattresses, and clothing. Several witnesses described a clear ethnic element to the targeting of victims. A year-old witness said: She said she and many other women and children were saved by a female Liberian who intervened to stop them from being killed. A year-old man from Burkina Faso described seeing 25 people killed and noted what he believed to be a clear motive for the attack:. Hundreds of people had fled to the town prefecture during intense fighting between the two armed forces.

He said that there were more bodies in the surrounding area that he had been unable to count. Witnesses said that the perpetrators tied the victims together, then slit their throats. Human Rights Watch documented at least 30 deaths from indiscriminate shelling, in what likely amount to war crimes.

I put my hand up to my head and saw blood running down my arm from my head. A Senegalese man nearby took shrapnel to his stomach and died…. When the shell exploded, there was a wind—Vooom—that blew out, with an intense heat. Six men were having tea and chatting in a small market alleyway when one shell exploded several meters away; all were killed.

Four other witnesses described the situation similarly, including one whose younger brother was wounded in the stomach and later died at the hospital. When Human Rights Watch visited the scene in July , hundreds of holes were still visible in tin roofs, metal doors, concrete walls, and anything else within 15 to 20 meters of where the shells exploded. The UN Human Rights Division investigated on the day of the attack and reported that at least six 81 mm mortar shells were fired, killing at least 25 and wounding another Similar attacks on residential areas killed at least nine more between March 11 and 24; in one such attack, a women and her infant were killed.

Human Rights Watch documented more than killings by pro-Gbagbo militias, mercenaries, and armed forces in Abidjan as the Republican Forces progressively took over the city. Killings continued until the last days that Gbagbo forces remained in certain neighborhoods. Credible sources, including local human rights groups and neighborhood leaders of immigrant populations, had information about similar killings in other neighborhoods, like Treichville and Plateau, suggesting that the total number killed by pro-Gbagbo militias during this period is probably higher.

Bodies were often burned, sometimes en masse, by pro-Gbagbo militiamen or by residents who could no longer tolerate the smell—leaving no trace except for small bone fragments. After pro-Gbagbo forces pushed them back in subsequent days, they targeted and killed dozens of perceived Ouattara supporters in the area. A year-old woman who remained in Williamsville through most of the violence because her parents were too old to flee told Human Rights Watch:.

Killings became increasingly frequent as the Republican Forces moved closer to Abidjan. An Ivorian driver described the March 28 killing of three Malian butchers by militiamen wearing black t-shirts and red armbands. The men shot the butchers as they were fetching a cow in Williamsville. While militiamen were often perpetrators, witnesses also identified regular security forces in some attacks. As the southernmost neighborhoods of Abidjan—opposite where the Republican Forces entered the city—they were two of the last three neighborhoods to fall.

As pro-Gbagbo militiamen attacked on April 2, hundreds fled toward the Force Licorne base nearby.

Upon hearing that the Licorne base could not house them, residents continued toward Koumassi. One witness described what followed:. Another witness interviewed by Human Rights Watch watched the April 7 execution of four brothers at a militia checkpoint near the same Camp Commando, located near a main entrance to Koumassi. In the largely Muslim Mami-Faitai section of Yopougon, Human Rights Watch saw what appeared to be eight common graves, each containing between 2 and 18 bodies according to people involved in the burials. Residents described how seven attackers in BAE the anti-riot unit uniforms descended on the checkpoint just after midnight on April 11 and killed 18 people.

A survivor who pretended to be dead after being shot told Human Rights Watch:. A year-old man, who lived in the same neighborhood and lost five sons when militiamen climbed into his compound around 9 a. At least 9 occurred, like the one described above, during the April 12 attacks. Rapes also continued in subsequent days, however, as some women tried to return home to get essential belongings for their families then in hiding.

Killings within areas controlled by the militias continued through the final days of the battle for Yopougon. On April 25, pro-Gbagbo militiamen took advantage of a brief movement by the Republican Forces out of Yopougon Andokoi to set up a roadblock. Two Malian brothers came into the neighborhood around noon, thinking it was safe, and were stopped at the checkpoint. The older brother, interviewed by Human Rights Watch, escaped but looked back to see that his year-old brother been stopped. They destroyed hundreds of homes, and according to witnesses, they detained, bound, and executed two Malians.

One was on his way into the area to save his mother who had been unable to flee earlier violence. Yopougon residents from both political parties said they had seen a few well-known militia leaders in and around the sub-neighborhoods of Yopougon where large numbers of killings occurred. Witnesses described repeatedly seeing militia leader Bah Dora in the area of Toit Rouge.

By March 29, after a month of tense fighting with primarily pro-Gbagbo militias and mercenaries, the now-created Republican Forces controlled the west. Fighting continued, however, through the first week of May, as pro-Gbagbo militiamen fought on in their stronghold of Yopougon neighborhood. However, wherever they met stiff resistance once armed conflict began—primarily in the west and Abidjan—soldiers systematically targeted civilians perceived to support Gbagbo.

Men, especially youth, were particularly targeted for their perceived affiliation with militias, but the elderly, women, and children were also killed. In total, hundreds were killed, most along ethnic lines, and dozens of women were raped. These abuses at times implicated high levels of the Republican Forces leadership, either directly or through command responsibility.

Armed clashes between pro-Ouattara and pro-Gbagbo forces began in the west on February 25, around the town of Zouan-Hounien. As combat waged throughout March, the Republican Forces targeted alleged pro-Gbagbo civilians. Soro visited the Republican Forces in Toulepleu on March 9 and 10, which does not appear to have reduced the abuses. In a few towns and villages, the Republican Forces arrived sooner than expected, before most people had taken flight, and opened fire as the panicked population tried to flee into the surrounding bush.

Witnesses said the Republican Forces often went house-to-house after occupying a village, killing many who remained. She escaped through a window, ultimately fleeing to Liberia. After working through the towns and villages, some Republican Forces fanned out on foot on the smaller roads into areas where residents work on cocoa plantations—killing additional people who believed they had fled to safety.

In one of several such accounts, a year-old woman told Human Rights Watch:. As the Republican Forces swept through, those who were elderly or ill, as well as family members who refused to leave loved ones who were unable to flee, often remained behind in their houses. In at least several instances, Republican Forces locked these people in one or several village houses and killed them in the days that followed. She was raped, her husband was killed for trying to defend her, and others were executed:.

Five of the seven captives died immediately, all of them over 50 years old, and the witness had three gunshot wounds in his left leg. They found a car that took them to Guiglo, where the Red Cross treated him. Faced with another imminent attack by the Republican Forces in Guiglo, the year-old man spent two weeks traveling more than kilometers on foot to cross into Liberia and find refuge in a village there. Human Rights Watch documented 23 cases of rape and other sexual violence by the Republican Forces as they advanced through the west.

Credible reports from humanitarian organizations working along the Liberian-Ivorian border suggest dozens more cases. In a few instances, combatants seized women and girls during their initial attack on a village, forced them into the surrounding bush, and raped them. A year-old woman from Bohobli, a village near Toulepleu, decided not to flee as the Ouattara forces advanced because her grandmother could not leave and because of her own disabled foot.

She told Human Rights Watch that three armed men entered her house. One fighter killed the grandmother with a machete, while the other two dragged the woman into the bush, where one raped her. In the majority of documented cases, fighters held women captive in houses for one or several days, gang raping them repeatedly before moving on to the next town or village.

Around March 7 or 8, the Republican Forces moved through Basobli, about 10 kilometers from Toulepleu toward the Liberian border. While most inhabitants fled once they heard that Toulepleu fell, a year-old woman interviewed by Human Rights Watch stayed to look after her brothers and sisters:. The Bangolo events are not just imputable to our movement….

As discussed below in the section on the final battle for Abidjan, Ousmane Coulibaly was in charge of troops in Yopougon neighborhood that witnesses and victims repeatedly implicated in killings, torture, and arbitrary detentions.

Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte d’Ivoire | HRW

Ousmane Coulibaly was not named as having ordered such crimes, but was a commander of operations overseeing troops that engaged in such acts. Human Rights Watch interviewed eight women who witnessed the events, as well as several people who helped count or bury the bodies in the subsequent days.

Five witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch clearly identified Republican Forces among the attackers, saying they arrived in trucks, 4x4s, and on foot in military uniforms. Others described seeing two pro-Ouattara militias that worked closely with the Republican Forces in committing abuses against the civilian population: However, according to witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the pro-Ouattara forces executed men not believed to be militia members, including boys and older men.

A year-old woman described the killing of her husband as well as dozens of others, in a statement similar to numerous others:. One was the pastor, riddled by bullets in his religious attire. The pattern of abuse first seen during the Republican Forces military offensive in the west continued as they captured Abidjan in April and proceeded to search for weapons and militiamen.

As in the west, the Republican Forces took control of areas to find that many from their ethnic groups had been murdered by retreating Gbagbo militiamen. At times in systematic and organized operations, and at times in simple revenge, the Republican Forces engaged in collective punishment against young males from ethnic groups aligned with Gbagbo—committing extrajudicial executions in neighborhoods and detention sites and subjecting scores more to inhumane treatment that at times reached the level of torture.

Human Rights Watch documented 95 killings by Republican Forces soldiers during search operations during and subsequent to active fighting with pro-Gbagbo forces. The vast majority of killings documented by Human Rights Watch took place in Yopougon, a neighborhood heavily concentrated with Gbagbo supporters and former militia bases.

Yopougon, with a population of around 1 million, is divided into dozens of smaller sub-neighborhoods. Koweit was one of the last areas of Abidjan to fall, with fighting ending around May 3. In the days and weeks that followed, the Republican Forces conducted house-to-house searches. Males from pro-Gbagbo groups appear to have been targeted for abuse. Human Rights Watch also documented one case of rape. A year-old woman from Yopougon Koweit described how she was brutally raped by a Republican Forces soldier on May 8, then saw the Republican Forces kill 18 youth:. A witness described five men being stripped, lined up, and machine gunned by a soldier.

Four victims died instantly; the fifth, shot in the thigh, pretended to be dead and later crawled to a nearby house. The witness, a friend who lived nearby, went to him, and the man asked for water. As the witness went for water, he heard several gunshots. The killings began immediately after the Republican Forces took control of the neighborhood.

On May 3, a witness watched as soldiers executed a year-old man at point-blank range after accusing him of renting a room to a pro-Gbagbo militiaman. Another witness described seeing the Republican Forces slit the throat of a youth in front of his father after finding a Kalashnikov and grenade in his bedroom during a 4 a.

The witness was stripped and forced to hand over his laptop computer, cell phones, and money. The witness, like many others interviewed by Human Rights Watch, wanted to flee Abidjan to his family village, but had no money for transportation since the Republican Forces had taken everything. A Republican Forces commander told Human Rights Watch that, after heavy fighting from April 12 to 19, his forces consolidated control of Yaosseh around April Eleven witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch described how, between April 25 and 26, the soldiers killed at least 30 unarmed men, mostly youth from pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups.

Most witnesses said the majority of victims had not been active militia members, who fled around April A year-old boy saw his year-old cousin shot and killed by soldiers as the two sat outside a health center at 2 p. The witness was spared because of a serious medical condition which the soldiers said made clear he had never been a militiaman. Another witness described how soldiers entered and opened fire into a neighborhood restaurant, killing eight males inside. As in Koweit, houses in Yaosseh were systematically pillaged, according to residents who witnessed the pillaging and who returned to find their houses emptied of all valuables.

Witnesses described a few instances in which senior officers intervened to stop extrajudicial killings, including a case in the Gesco neighborhood of Yopougon in late April. A year-old woman described what happened on April Some of those captured had been identified by local residents as pro-Gbagbo militiamen who had committed crimes against pro-Ouattara communities, but the soldiers did not appear to have any information in most cases that linked those executed to any crime.

Two former detainees in the 16th precinct police station similarly described the execution of at least four young men during the first night of their detention, around May 5. On May 15, a Human Rights Watch researcher saw a burning body less than 30 meters from the 16th precinct, still controlled by the FRCI, and was told by numerous witnesses at the scene that it was a pro-Gbagbo militiaman who had been caught and killed.

The following day, two people who participated in the capture and witnessed the execution described the events. A Human Rights Watch researcher presented evidence about summary executions around the 16th precinct to Commissioner Lezou—a member of the Republican Forces then in charge of the precinct. Lezou adamantly denied that executions took place, saying that any bodies found on the streets were from the fierce combat between April 14 and He also denied that a body was burned across the street from the precinct on May 15, even though the Human Rights Watch researcher said he had seen it himself.

Victims were taken out of the station at night over two days and executed on grounds nearby, said several detainees and a neighborhood resident. Several people executed were militiamen allegedly implicated in dozens of killings and, according to residents, in possession of large caches of arms. Human Rights Watch documented dozens of cases of torture and inhumane treatment of detainees by the Republican Forces.

During and after the military offensive in Abidjan, hundreds of youth from pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups were arrested and detained—often at abandoned police stations and military bases as well as in makeshift detention facilities like gas stations and the GESCO complex. Almost every former detainee interviewed by Human Rights Watch described being routinely beaten, most often with some combination of guns, belts, clubs, fists, and boots, as Republican Forces soldiers ordered them to reveal the location of weapons or militia leaders.

Most were detained simply because of their age, ethnic group, and neighborhood residence. Another detainee described how the Republican Forces forcibly pulled out several of his teeth during questioning after cornering him on a small road in Yopougon Wassakara in mid-April:. The prohibitions of war crimes and crimes against humanity are among the most fundamental prohibitions in international criminal law. Such acts include murder, rape, and persecution of a group on political, ethnic, or national grounds.

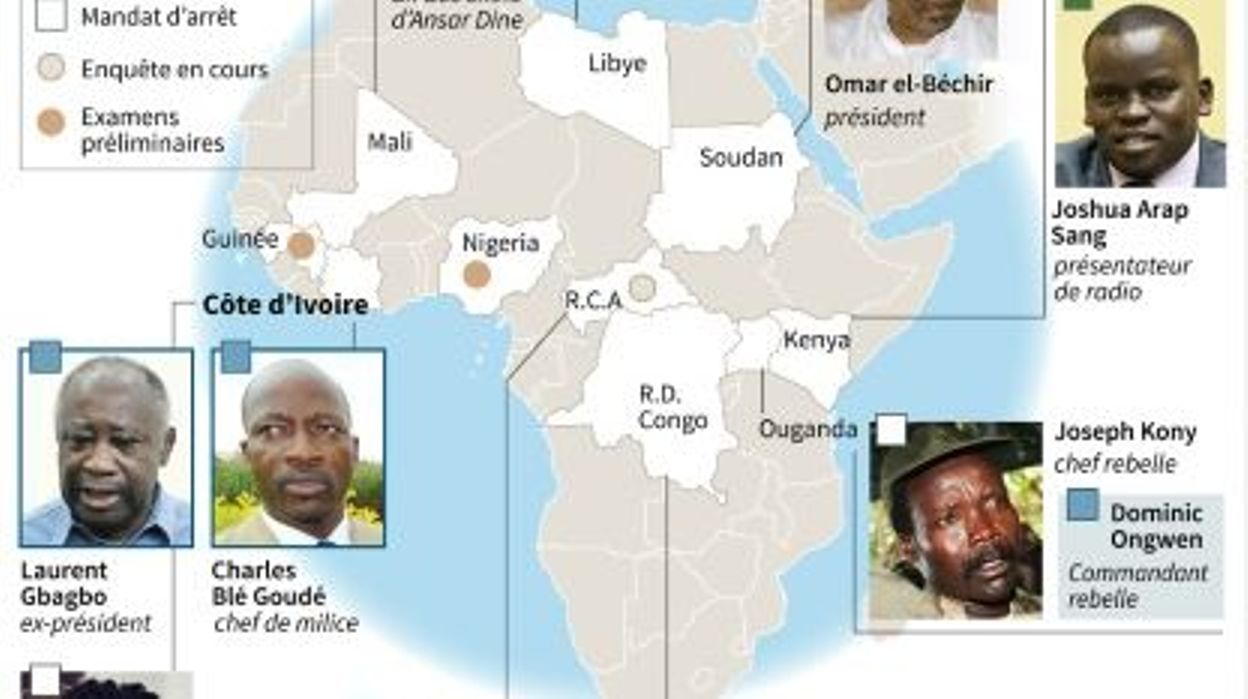

Based on its fieldwork, Human Rights Watch has identified the following people as implicated in responsibility—either for their direct participation or for command responsibility—for the grave crimes committed during the post-election period:. Laurent Gbagbo — The former president was the commander-in-chief of armed forces that committed war crimes and likely crimes against humanity.

Despite clear evidence of grave crimes committed by his military and militia supporters, Gbagbo neither denounced nor took steps to prevent or investigate the crimes. When his presidential palace was overtaken by the Republican Forces, they found an enormous supply of heavy weapons—many of the same types that had been used in indiscriminate attacks that killed civilians.

Gbagbo was arrested on April 11 by the Republican Forces; he was charged by prosecutor Simplice Koffi on August 18 with economic crimes, including embezzlement, robbery, and misappropriation. His militiamen often worked closely with elite security force units in targeting Ouattara supporters. Immediately following this call, Human Rights Watch documented a sharp increase in violence by the Young Patriots, generally along ethnic or religious lines.

He is believed to be hiding in Ghana, although reports have previously placed him in Benin and the Gambia. General Philippe Mangou — The head of the armed forces under former President Gbagbo, Mangou oversaw troops who appear to have committed war crimes and likely crimes against humanity. These crimes were widely publicized in Ivorian and international media, yet Mangou took no meaningful action to prevent further crimes or to investigate those responsible for repeatedly targeting Ouattara supporters.

The only thing that counts is the will and determination of each person…. Everyone will be enrolled in the army. Taken as a whole, for both their widespread and systematic nature, the crimes committed under his command likely constitute crimes against humanity. A military prosecutor brought Bi Poin in for questioning on May 13, but released him on the promise to appear when summoned. Taken as a whole, the crimes committed under his command likely constitute crimes against humanity.

Treichville neighborhood, where the Republican Guard camp is located in Abidjan, suffered particularly. A military prosecutor charged him on August 11 for his role in violent crimes committed during the post-election violence. He was present for and helped orchestrate the attacks, according to victims and witnesses present, in which West African immigrants and northern Ivorians were targeted on ethnic grounds. Large-scale violence against perceived Gbagbo supporters often followed.

The station also encouraged attacks against UN personnel and vehicles, and such attacks occurred repeatedly throughout the crisis. Maho is believed to have fled from Yopougon before the Republican Forces took control. His current whereabouts are unknown. No credible action appears to have been taken by Loss either to prevent the crimes or to punish those responsible in his ranks.

At time of writing, he remains a Republican Forces commander and has, according to Ivorian media reports, been named a deputy commander in an elite Ivorian force that is to be trained in France. A report by the humanitarian news service IRIN implicated Ousmane in overseeing forces who committed extrajudicial executions against Liberian and Sierra Leonean mercenaries.

These occurred over several weeks, and no action appears to have been taken by Coulibaly either to prevent the crimes or to punish those responsible. At time of writing, he remains a commanding officer in the Republican Forces. Several initiatives are under way to promote accountability for the grave crimes committed during the post-election period. It provided a confidential annex of those identified as most responsible to the International Criminal Court prosecutor, who has received authorization from an ICC pre-trial chamber to open an investigation into grave crimes committed during the post-election violence.

At the domestic level, prosecutors have brought charges against at least military and civilian leaders in the Gbagbo camp for their roles in the crisis. Military leaders have been charged with crimes including murder and rape, which could be underlying crimes that constitute war crimes or crimes against humanity. Civilian leaders, for the most part, have been charged with economic crimes and crimes against the state. In stark contrast to the efforts to prosecute Gbagbo and his allies, however, no member of the Republican Forces has been arrested or charged at time of writing.

On March 25, , the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution that established an independent international commission of inquiry to investigate human rights violations committed after the presidential runoff and to identify those most responsible for crimes committed so that they could be brought to justice. In its summary, the commission concluded that:. To that end, the commission prepared an Annex of people against whom their evidence reasonably suggested individual criminal responsibility.

The failure to make public the Annex or to provide it to the government and the domestic prosecuting authorities recalled a previous international commission of inquiry. In , a similar commission was tasked with investigating grave crimes committed during the civil war. Its detailed report, which provided evidence of crimes against humanity by both sides, was handed to the UN Security Council in November The report has still not been made public.

Immediately after the international commission of inquiry published its report, the Ouattara government announced that it was creating a national commission of inquiry. For two months, no formal charges were initiated against those detained, leading groups including Human Rights Watch to call on the Ouattara government to end what appeared to be a violation of both Ivorian and international law. Several days later, authorities began to bring formal charges.

The alleged crimes primarily appear to be crimes against the state and economic crimes. Charges continued to be brought by both civilian and military prosecutors in August and September. At time of writing, there were at least individuals from the Gbagbo camp charged for crimes committed during the post-election period. At time of writing, no member of the Republican Forces had been charged related to the grave crimes committed during the post-election violence. He also said that, before domestic prosecutions would take place, the government was waiting for the ICC to act—despite the fact that the ICC has historically taken only a few cases in situations under investigation.

No progress is evident regarding the investigation of crimes committed during the Abidjan offensive and subsequent weeks. On December 14, , and May 3, , President Ouattara renewed the 12 3 declaration. This time limitation needlessly cut off the proposed international investigation into grave crimes committed during the decade prior to the most recent violence and ignored the desires of most leaders of Ivorian civil society, who stress the importance of investigations going back to , given the gravity, scale, and complete impunity for these crimes.

On June 28, Bensouda and Justice Minister Kouadio signed a formal agreement in which the Ivorian government promised full cooperation as outlined under part 9 of the Rome Statute. They noted that there was little consultation with civil society in making the choice and, given his partisan political background, they were uncertain as to whether he would inspire groups on both sides to feel comfortable with and confident in the commission. On September 5, the council of ministers adopted a decree naming the vice-presidents and commissioners. The vice-presidents are leaders from the traditional, Muslim, and Christian authorities, respectively.

Many of the causes of the most recent Ivorian conflict are clear: By the end, their acts included war crimes and likely crimes against humanity, with responsibility up to the highest levels of military and civilian leadership. While logical in apportioning political blame, the argument fails under norms of human rights and international humanitarian law. High-level commanders on both sides are implicated in war crimes and likely crimes against humanity.

At times, the violence they engaged in and oversaw reached a shocking level of depravity. In some respects, the nature of the violence should come as little surprise. And no manner how many people were killed, no one on either side had been held responsible for their acts.

This sidelining of justice was often abetted by key actors in the international community, who believed justice was incompatible with ongoing peace negotiations. Some continue to believe so, failing to learn from lessons past, when postponing justice meant persons implicated in grave crimes remained entrenched in positions of power.

When tensions again mounted, they returned to inflicting violence against civilians, having learned that there was almost no cost to doing so. While life has started to return to normal for large parts of the population, particularly in Abidjan, insecurity continues for many who are thought to have supported Gbagbo—especially young men perceived as militiamen based on their age and ethnicity. More than , refugees remain in either Liberia or Ghana, afraid to return home. Ouattara stated that he had "added the word dialogue" to the more common "TRC" nomenclature because "that is part of our customs," and has said that the proposed entity would draw from the experience of South Africa's TRC.

Transitional justice reflects judicial and non-judicial efforts to ensure accountability for human rights abuses, economic crimes, and other violations of the rule of law during transitions—from a period of conflict, or during which legal accountability has otherwise not been guaranteed, such as dictatorship—to a context where government institutions provide or are building mechanisms and institutional capacity to ensure democratic and legal accountability.

During the past decade, in both the northern and southern regions of the divided country, national elections were not held and the rule of law was often enforced arbitrarily or not at all. This frequently permitted human rights abuses, economic crimes, and security force coercion to go unpunished, and public services and state institutional capacities suffered.

Transitional justice efforts often attempt to balance disparate objectives, including justice, accountability, reconciliation, security, and peace building, which In some cases may be seen conflicting. They are often controversial; vanquished political interest groups may view such efforts as a means for their victorious opponents to carry out retribution, and if alleged abuses by the victorious side are not addressed, such efforts may be seen as furthering allegations of impunity from justice.

In multiple countries emerging from conflict, transitional justice efforts have garnered international support, both financial and political. Early indications that such support may be forthcoming were the U. Human Rights High Commissioner, Mary Robinson, visited as part of an effort to promote national reconciliation efforts. The group met with leaders of key political groupings, including former president Gbagbo, who they reported had accepted his electoral loss to Ouattara.

Their discussions reportedly addressed such issues as "security and disarmament, accountability and justice, the revival of the economy, youth unemployment and the empowerment of women Despite his focus on reconciliation and unity, and after stating that "reconciliation cannot happen without justice," Ouattara also announced that Gbagbo and one of his two wives, Simone, would be subjected to a judicial investigation by the minister of justice and face unspecified charges "at a 'national level and an international level'," along with unspecified supporters. On April 16, the Justice Minister stated that such probes would focus on "crimes of blood," arms purchase, or embezzlement by former Gbagbo regime leaders.

On April 27, the government reaffirmed that it was carrying out an unspecified criminal probe against Gbagbo, his wife Simone, and other close associates over alleged human rights abuses and other crimes. According to the Justice and Human Rights minister, the prospective plaintiffs were slated to be questioned during the first week of May. Ouattara pledged that the physical integrity and safety of Gbagbo and his first wife, Simone, 35 would be guaranteed, that their rights would be respected, and that they would be accorded dignified treatment.

Ouattara also said that he had requested that the International Criminal Court ICC investigate alleged crimes arising from the crisis. It said that the OTP "has been conducting a preliminary examination in Ivory Coast" and was collecting "information on alleged crimes committed there by different parties to the conflict.

Human Rights Council probe prior to opening his own formal investigation. The Human Rights Council human rights violations investigation is being undertaken by a three-member Commission of Inquiry appointed on April 12 by the council's president. In addition to human rights abuses, abuses of civic freedoms and efforts to ensure them are likely to garner considerable attention during anticipated reconciliation processes. During the post-electoral crisis, political protests were often violently suppressed, as described elsewhere in this report, and there were severe restrictions on press freedoms.

Such actions generally targeted pro-Ouattara supporters but pro-Gbagbo press outlets also faced increasing coercion by pro-Ouattara elements see textbox entitled "Control of Information". Under the Ouattara government, there have also been numerous reports of retaliation by pro-Ouattara supporters, notably targeting members of Gbagbo's FPI political party, the headquarters of which was ransacked during recent fighting.

Several pro-Gbagbo news outlets have also faced de facto limitations and engaged in security-related self-censorship. Four newspapers presenting a pro-Gbagbo perspective were reportedly not being published as of late April, and the printing presses and facilities of some had been destroyed. Journalists and publishers of such outlets have also reported being targeted by coercive threats from armed men, despite a publicly stated commitment by Ouattara government officials to ensure respect for press freedoms. A longer term challenge necessary for ensuring long-term peace will be disarmament, demobilization and reintegration DDR , both of regular forces and irregular militia, and military and police-focused security sector reform SSR.

In mid-March, Ouattara decreed the establishment of the FRCI, a new military incorporating the former Forces Nouvelles and the national military formerly loyal to Gbagbo. Integrating the two forces is likely to prove challenging, as had been the case with respect to similar efforts pursued under the Ouagadougou Political Agreement OPA , as discussed in Appendix 1 of this report.

Some of the same issues that challenged DDR and SSR processes under the OPA—for instance, determining the selection, number, and rank of candidates who will be accorded officer status or be retired from service—are likely to pose continuing difficulties. Rivalries between FN and allied elements and those who opposed Ouattara may also cause controversy. Such rivalries may be heightened by reported current government efforts to recruit new soldiers and police, notably from among youth militia who supported Ouattara during the civil conflict.

The move is likely motivated, in part, by the Ouattara administration's desire to ensure that national security forces are loyal, but may prompt charges of ethnic favoritism during a period when the government is also trying to promote national and ethno-regional unification. Inordinate military political influence by former FN FRCI elements is another difficulty that may face the government. A final important short-to medium term challenge for Ouattara is the need to rebuild state legitimacy and operational capacity, including through the conduct of long-delayed legislative elections; the appointment of ethno-regionally diverse incumbents to fill numerous government posts; the reunification of the national territory and the extension of state authority throughout the north; and the centralization of the treasury.

The overriding post-crisis objective, national political unification, is likely to remain a key challenge for an extended period. Ouattara will also have to counter perceptions among many Gbagbo supporters that he came to power as a result of French neo-colonial influence and related a multilateral imperialist plan.

Security Council—they nevertheless present a potent, potentially highly divisive political problem. The war, along with the political events that contributed to and followed it, is discussed in Appendix B. The post-electoral crisis and conflict directly threatened long-standing U. While the crisis did not directly affect vital U. Also indirectly at stake were broad, long-term U. It had among the strongest economies in the region, attracted significant foreign investment, notably from France, and was a top world producer of cocoa and coffee, among other exports.

It remains the world's largest cocoa producer. Its economic success was built on pro-agricultural policies, often favorable export prices, expanding production, and the labor, in the southern cocoa belt, of migrants from its northern regions and northern neighbors. They worked cheaply in exchange for jobs, land, and farming rights in the south, where a dynamic multi-ethnic society evolved.

Significant numbers of military officers were integrated into provincial civilian administration, and promotion through the ranks was reportedly dependant on political loyalty. The military played no central institutional role in domestic affairs, however, and did not threaten the ruling regime. His policies emphasized social inclusion, cooperation, and reinvestment of national wealth in the economy. His semi-authoritarian-style regime was marked by stability, and although it coercively suppressed political opposition parties, a transition to multi-party politics occurred late in his tenure.

In the mids, calls for democratization, episodic social unrest, and political tensions emerged, spurred by long-term cocoa price and production declines, growing national debt, austerity measures, and decreasing access to new tree cropping land. While resource scarcities underlay these tensions, social competition increasingly began to be expressed in terms of ethnic, regional, and religious identity. The large, mostly Muslim populations of immigrant workers and northern Ivoirians resident in the south faced increasing resistance by southerners and the state to their full participation in civic life and citizenship.

It defined southerners as "authentic" Ivoirians, in opposition to "circumstantial" ones, that is, northerners and immigrants. It helped fuel increasingly volatile national politics encompassing electoral competition; military, student, and labor unrest; conflict over land rights; and periodic mass protests, some violent, over economic issues. These developments also presaged subsequent political developments: A series of internationally supported peace accords, the most recent signed in , laid out a roadmap for disarmament, national reunification, and elections leading to a return to democratic governance after years of political crisis, but all remained only partially implemented.

Both candidates claimed to have won the runoff vote and separately inaugurated themselves as president and appointed cabinets, forming rival governments. Both claimed to exercise national executive authority over state institutions and took steps to consolidate their control. Ouattara, popularly known by his initials, ADO pronounced ahh-doh by Ivoirians , based his victory claim on the U.

These showed that he won the election with The results showed Gbagbo winning Most of the international community, including the United States, endorsed the IEC poll results as accurate and authoritative, and demanded that Gbagbo to accept them and cede the presidency to Ouattara. It ruled that he had received The Council's decision allocated 2.

Gbagbo, citing the Constitutional Council's constitutionally authorized decision, asserted that he was the legally elected president and has rejected international calls to step down. His victory claim was widely rejected internationally, however, because the Special Representative of the U. Ouattara as the winner.

"The Best School"

Alassane Ouattara with an irrefutable margin as the winner over Mr. The decision of the Constitutional Council was widely viewed internationally and by the Ivorian opposition as having been motivated by partisan bias. The council's decision was preceded by what appears to have been a coordinated effort by Gbagbo supporters to discredit selected runoff poll results before they were announced by the IEC—once it had become clear, based on partial preliminary poll results, that Gbagbo would likely not win the poll—and to disrupt or extend past the three-day deadline IEC validation of the results, creating a rationale for the council's review and rejection of the IEC's determination.

The incident disrupted the workings of the IEC and reportedly caused it to miss its legal deadline for announcing the results, creating the basis for council review. The council's decision was also viewed skeptically because it resulted in the statistically highly unlikely annulment of the , votes, a number equivalent to Some observers also contend that under Article 64 of the national electoral code, the council had the authority to cancel the entire election, but not part of it, and to order new elections in the case of a cancellation.

The president of the council, however, has contended that electoral precedent gave the council the authority to order a partial cancellation; he cited as the basis of such authority the partial cancellation of presidential election results. SRSG Choi was designated to serve as an independent election certifier of the presidential election by the U. Choi certified all the key stages of the pre-poll day electoral process based upon a framework and criteria designed in consultation with all the Ivoirian parties and other stakeholders, such as the U.

Choi, who in his certification statement declared that "the second round of the election was … generally conducted in a democratic climate," rejected what he described as the "two essential arguments" informing the Constitutional Council's decision. The first related to "the use of violence in nine departments in the North which prevented people from voting. Choi also later asserted that while his certification of the runoff vote had taken into account all claims lodged by Gbagbo, the Constitutional Council had taken into account complaints not made by Gbagbo and cancelled results from departments where he had not contested the voting results or process.

The IEC's voter participation figures bore out the assertion that the average voter participation rate was as high in northern areas at issue as in most other areas of the country, and surpassed those in several southern regions. Choi also rejected the council's second core rationale for overturning the IEC's decision, which focused on allegations that "the tally sheets in [ He also stated that such party signatures were not legally required; under the Ivoirian electoral code, he stated, only the signatures of the President and assessors of local polling offices are required to certify the tally sheets.

SRSG Choi's certification of the IEC-announced runoff results and the build-up of international pressure on Gbagbo to stand down infuriated President Gbagbo and his political supporters and ratcheted up political tension and violence see " Political Tension and Violence ," below. The Gbagbo government asserted that the international community's rejection of the Constitutional Council's decision and its efforts to force him to concede the presidency infringe on Ivorian national sovereignty and the constitutional rule of law—even though the Gbagbo government, among other signatories of the and prior peace agreements, had agreed to the United Nations' electoral certification mandate.

The order was rejected as illegitimate by the United Nations and had no practical effect. In late January , UNOCI had an authorized strength, through mid, of 10, personnel, but had not fielded this large a contingent; it had a deployed field strength of 9, troops and police. The mission has been temporarily supplemented by several hundred additional troops from the neighboring U.

It was attempting to obtain additional troops to meet its authorized personnel cap. It monitors military aspects of peace accords and an arms embargo; assists with disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of armed groups and parties to the conflict; provides support for security sector reform, humanitarian aid deliveries, the re-establishment of state administration and law and order; adherence to human rights laws; aids efforts to conduct free and fair elections and related processes of citizen identification and voter registration; and protects U.

In early March, two helicopter gunships arrived, and a third was en route; they were seen as enabling UNOCI to more forcefully address military attacks on its forces or persons or property under its protection. The Gbagbo government and its supporters took an uncompromising stance with regard to what they saw as Gbagbo's legally binding, incontrovertible electoral win. They pursued diverse efforts to ensure that he remains president. These efforts included attempts to ensure support among civil servants and the military by asserting control over various revenue and credit streams to ensure salary payments; attempts to eject UNOCI and impede its operations; violent raids on opposition strongholds; and pursuit of an international public relations campaign to promote the Gbagbo case.

The public relations campaign included a grassroots media outreach effort by Gbagbo supporters, who distributed government and pro-Gbagbo press articles and blogs, in some cases promoting vitriolic rumors and conspiracy theories. Coverage of such alleged collusion reportedly featured prominently and frequently on state TV and other pro-Gbagbo media, part of what the U. High Commissioner for Human Rights described as "an intensive and systematic campaign" by state-owned radio-television RTI to promote "xenophobic messages inciting hatred and violence [and France has been active in the Ivoirian peace process since the start of the conflict.

It also aided other foreign nationals, including Americans, many of whom French forces evacuated from the country in late In February , Operation Licorne was authorized by the U.

“They Killed Them Like It Was Nothing”

The French retaliated by bombing the Ivorian air force, destroying almost all of it. Licorne was also involved in protecting French citizens and property during violent riots that targeted UNOCI and French troops and civilians after the attempted resumption of conflict. Licorne, which at its largest size included 4, personnel and later dramatically reduced, was reinforced during the crisis, during which it consisted of about 1, based mostly in Abidjan. Post-crisis plans call for it to be reduced in size, to a force strength of about troops.

The Licorne force includes mechanized infantry, military police trained in riot control, engineers, and a special forces detachment. It operates eight helicopters and is backed by Operation Corymbe , a standing contingent French naval presence in the Gulf of Guinea comprised of an amphibious helicopter carrier equipped with a bed hospital, and can be reinforced on as-needed basis by French standby forces based in Gabon and Senegal.

The Gbagbo camp's information campaign also employed the use of official Ivorian government websites and foreign lobbyists to make the government's case. In the United States, a short-lived, soon-abandoned effort by Lanny J. Davis, a Washington lobbyist and former special counsel to former President William J. Clinton, garnered substantial attention. Gbagbo also pursued a series of alternative actions that might have allowed him to remain a key government leader if he was forced to cede the presidency. He suggested that he might be willing to entertain a negotiated solution to the crisis and called for Ouattara and himself to "sit down and discuss" a way out of the crisis with him.

Gbagbo also invited renewed international mediation to negotiate a resolution of the crisis see " Regional Diplomacy ," below. On December 21, he addressed the Ivorian nation on TV and stated that he was "ready—respecting the constitution, Ivorian laws and the rules that we freely set for ourselves—to welcome a committee of evaluation on the post-election crisis in Ivory Coast. In discussions with a visiting ECOWAS heads of state in late December, Gbagbo also reportedly demanded a vote recount and, were he to depart his post, a grant of amnesty for any criminal charges that he might face as a result of post-electoral human rights abuses associated with his control over state institutions and security forces and his refusal to cede the presidency.

In addition to asserting its case internationally and suppressing ant-Gbagbo demonstrations, the Gbagbo administration undertook efforts to control the flow of information reaching the Ivorian population immediately after the disputed runoff. SMS cell phone text messaging services were also suspended after the runoff.

Contention over control of media has involved violence in some cases. The crowd's action was violently suppressed by security forces, which opened fire on the crowd, killing an estimated 20 or more persons and injuring many more. RTI has also been the target of attempts to hinder broadcasts; in late December, its TV signal was not available in some areas of the country, and was dropped from satellite rebroadcast in the West Africa sub-region.

There were also raids on numerous opposition-affiliated newspapers and printing presses, and at least nine foreign journalists were detained during the post-electoral period. Local journalists also faced coercive threats, detention, and beating by security forces. Some of the Gbagbo government's actions were partially reversed; opposition newspapers were publishing, and some formerly jammed banned radio stations began broadcasting anew. There were also new incidents of censorship and indications that the Gbagbo administration was seeking to impose greater regulatory control over the press.

Harassment of and threats against journalists also continued, prompting nine independent or pro-Ouattara newspapers to suspend operations in early March , although eight later resumed operation. Ouattara supporters were also accused by a the international and Ivoirian branches of the Committee to Protect Journalists of taking actions to "exact reprisals on their critics in the press," and pro-Ouattara press outlets, like those favorable to Gbagbo, were accused of publishing highly partisan, biased, and often false or conspiracy-centered information.

Security Council, regional organizations, and key donor governments involved in monitoring, vetting, or helping to administer the electoral process. President Gbagbo and his administration were the targets of intense and wide-ranging diplomatic, political, financial, and threatened military international pressure aimed at forcing Gbagbo to concede the election and had state power over to Ouattara see " International Reactions ," below.

According to UNOCI, the security situation in the weeks after the runoff were "very tense and unpredictable;" as a result, the United Nations temporarily relocated its non-essential staff to Gambia on December 6, The outer perimeter of the U. As of March 24, , U. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, also documented continuing reports of abductions, illegal detention and attacks against civilians.

Video of the fatal protest was distributed on the Internet.

Related Content

Part of a follow-up protest was fired on by state security forces, resulting in four fatalities, and a smaller, related rally was broken up by pro-Gbagbo youth militants "armed with machetes and firing automatic weapons into the air. Similarly, France called for a U. The total number of fatalities and abuses resulting from post-electoral violence was likely higher than the total documented by the United Nations; additional killings, detentions, and abuses were reported prior to the period covered by the U.

In addition, the national military reportedly did not release numbers of its own casualties or civilians killed by its members. HRW and AI, in particular, drew attention to a rise in apparently politically motivated use of rape as a means of intimidation. The three-month campaign of organized violence by security forces under the control of Laurent Gbagbo and militias that support him gives every indication of amounting to crimes against humanity.

There were also reports of mass graves. UNOCI attempted to investigate reports of three such graves, one in Abidjan, one in the south-central town of Gagnoa, near Gbagbo's place of origin, and one in the town of Daloa, but was prevented from accessing the sites by state security forces, some in mufti. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, stated, was a "clear violation of international human rights and humanitarian law. His semi-authoritarian regime creates a liberal, market-based and prosperous economy in south. Constitutional changes affecting electoral laws, seen as favorable to the incumbent, passed.

His bid highlights ethnic, regional, and religious political divisions within the national polity. Several incidents of military restiveness occur, and use of military in domestic crime suppression leads to abuses. Constitutional changes approved by July referendum, widely boycotted in north, requiring both parents of presidential candidates be Ivoirian-born citizens. State of emergency imposed before widely boycotted presidential election on October Rival political party post-poll violence ensues, but Gbagbo's win is ratified by Supreme Court.

Controversial legislative election held in late , but violence over claimed political disenfranchisement forces poll suspension in north. Government, albeit criticized over its human rights and judicial records, sponsors inter-party National Reconciliation Forum. After clashes with loyalist forces in south, rebel units withdraw and rapidly take control of the northern half of the country.

They form a political movement, later called the Forces Nouvelles , and eventually establish a basic administrative state in areas they control. Fighting decreases in late but continues into early Regional and international peace mediation ensues. A series of partially implemented key peace accords, each building on elements of preceding ones, signed: Elections are repeatedly delayed due to contestation over peace process, notably regarding the sequencing of disarmament, citizen and voter identification, and elections.

A government attempt to attack north results in nine French fatalities and one U. Violent anti-French protests follow. Gbagbo's electoral term ends in , but under emergency constitutional powers, underpinned by international community support for the ongoing peace process and the formation of a unity government, he retains power, pending elections. Electoral, disarmament, and state reunification processes proceed slowly due to political disputes.

Elections are finally held in late , but result in a contested outcome and the current political crisis. Several governments advised their citizens not to travel to the country and to depart it if they were there. Citing "the deteriorating political and security situation See " Humanitarian Effects and Responses ," below. Extensive recent fighting in the west, Abidjan, and in a growing number of other areas starting in March signaled that a new Ivoirian civil war was under way.

A growing number of indicators had previously signaled that such an outcome was a distinct possibility, and possibly "imminent. This was viewed as worrying because of Liberia's history of severe wartime human rights abuses and because such irregular forces might be difficult to prosecute, for varying reasons, if they were accused of crimes. According to the United Nations, some pro-Gbagbo youth groups and militias were being armed. Such actions were reportedly coordinated by high-ranking state officials and pro-Gbagbo militia, youth group, and political party leaders.

Such groups, including an ultra-nationalist, frequently xenophobic pro-Gbagbo youth group known as the Young Patriots, were reportedly coordinated with state security forces, in particular to identify and target putative opposition-affiliated "individuals to be arrested, abducted or assassinated and their residences. Pro-Ouattara youth groups reportedly carried out similar actions, and militant supporters of both presidential claimants were, in some cases, carrying out attacks on individuals and communities based on their targets' presumed ethnicity and putative political affiliation.

There were also reports and visual media evidence documenting live burnings of beaten victims, among other atrocities. Foreigners also became an increasing target of pro-Gbagbo supporters angered by international rejection of Gbagbo's claimed election and financial pressure on the Gbagbo administration, state media propaganda alleging that UNOCI and various foreign governments were collaborating with the FN, and related factors. On March 1, Young Patriots reportedly "rampaged through the business district of Abidjan Fighting in Abidjan was frequent.

It was reportedly first initiated by state security forces loyal to Gbagbo, which launched repeated raids on putative opposition strongholds in Abidjan in late and early These raids, which reportedly were associated with numerous extralegal detentions and extrajudicial killings, appear to be spurring retaliatory violence. The assailants were not identified, but were reported to be members of a Forces Nouvelles -affiliated fighting cell that calls itself the Movement for the Liberation of the Peoples of Abobo-Anyama MLP-2A.

The militia's name referred to the densely populated northern neighborhoods of Abobo and Anyama, where about 1. A similar armed anti-Gbagbo element, dubbed the "Invisible Commando," was also reportedly active. Some prior raids were resisted by residents of the area, but the February 23 clash signaled a significant escalation in violence and the most lethal clash up until that date in Abidjan between state security forces and armed elements opposing them, assisted by local youths and some defectors form the national military.

The February clashes appeared to spur a rise in such confrontations; multiple gun fights between Gbagbo and Ouattara forces reportedly occurred during the last week of February , and the fighting spread to other areas of the city on March 2. The ongoing clashes in Abidjan and elsewhere prompted Mangou to state on March 15 that pro-Gbagbo forces were prepared to go to war. Possession of this territory—provided that the FN can hold it—would give the FN control over much of the Ivoirian border with Nimba county in neighboring Liberia, where both pro-Gbagbo and Ouattara armed elements reportedly recruited ex-combatants from the Liberian civil war.

In early March, the U. There were reports that FN forces had taken control of two key towns, Duekoue, in the west, and the central town of Daloa, and seized two smaller towns in the east near the Ghanaian border. An additional possible harbinger of resurgence of military conflict were reports of possible violations of a long-standing U.

Recent Developments" text box, below. In late March, UNOCI reported that pro-Gbagbo state security forces "were repairing an MI attack helicopter"—possibly an aircraft that had been damaged by France in —and preparing multiple rocket launchers. The assertion followed reports that heavy weapons were increasingly being used within Abidjan. The prospect of renewed armed conflict had earlier been spurred by repeated calls by Ouattara aides for Gbagbo to be removed from office by force, and by a December 24 threat by ECOWAS to undertake such an action.

While the regional body later deferred military intervention, pending further negotiation, as of mid-January , the proposal remained the focus of active military planning see section entitled " Threat of Military Intervention to Oust Gbagbo ". The increasing tension and a rise in anti-UNOCI sentiment, which took the form of public demonstrations spurred by pro-Gbagbo media and party militants, resulted in multiple physical attacks on UNOCI peacekeepers and has hindered their movement.

On February 28, , pro-Gbagbo youth reportedly abducted two UNOCI peacekeepers, who were then detained at a state Republican Guard base for several hours before being released. Any continued actions obstructing and constricting UN operations are similarly unacceptable. UNOCI will fulfill its mandate and will continue to monitor and document any human rights violations, incitement to hatred and violence, or attacks on UN peacekeepers. There will be consequences for those who have perpetrated or orchestrated any such actions or do so in the future.

In late December, the U. He said an attack on it "could provoke widespread violence that could reignite civil war. On the other hand preventive action may not necessarily involve or even need military might or significant financial superiority. In his report on the prevention of armed conflict the then UNSG, Annan, stated that prevention requires cooperation between various state and non-state actors on the international scene; while the UN is pivotal, it is not always the organisation suited to lead international multilateral preventive action, preventive capabilities reside in other institutions as well as differing UN entities.

The question remains if they would be able to bear such responsibility working in isolation or in concert. Who the international community is, taken from a literal interpretation of community could be obscured by the expectation or the reality of all these entities acting together. This is further obscured by a differentiation of the entities that can act and those that cannot; those that will act and those that will not. The fact that the legal burden put on individuals, states and organisations differs makes it an uneven community of personalities; though this does not affect the legal force of any agreement concluded between such personalities.

An actor on the international scene may have both capacity and political will, one of them or neither. While the binding nature of the UNSC resolution may be of potential significance to the acceptance of the responsibility to protect, it does not add much to the definition of the international community in respect of the responsibility to protect. The I te atio al Co u it a d Mass At o ities. National and International Perspectives. Besson and Marti Eds. International Studies Review 11 1: Addis Imagining the International Community: The Constitutive Dimension of Universal Jurisdiction. Human Rights Quarterly 31 1: Nijman and Nollkaemper Eds.

European Journal of International Law 9: This is considered to be the major thrust of a responsibility to prevent; a negative obligation by states and the international community to refrain from committing genocide, war crimes, CAHs and ethnic cleansing. When viewed from a human rights perspective it is an obligation not to violate any of the component rights that comprise the R2P crimes. One may well ask if this is the sole legal content of the responsibility to prevent.

To answer this query, we have to consider the content of the obligation to protect. The ICISS on the other hand when expounding on the responsibility to prevent did not propose a critical legal definition of this responsibility entailed but suggested forms in which the responsibility could be exercised. The Commission suggested developmental assistance, advancement of democratic rule, mediation efforts, inducements and similar measures to prevent the violations of human rights.

Subsistence, Affluence, and U. These conventions primarily provide rules for the protection of human rights by stating what a human right is and exhibiting what would amount to a violation. Furthermore, the conventions have within their corpus, provision for monitoring or and ensuring the adherence of members states. On the other hand there is only so much that the UN and its subsidiaries can do to ensure compliance by member states if states do not wish to be bound or do not consider it in their best interests to be bound.

International law is not too explicit when defining the extraterritorial obligations of states to prevent violations of human rights that occur within the territory of states. However, as has been discussed above the international community has an obligation to prevent human rights violations. Encouraging democratisation without the use of force Due to the nature of post-colonial West African states, democratically elected governments recognised by the rest of the world are quite a new introduction to the political landscape. Good governance itself has been cited by the IMF and the World Bank as a requirement for economic development of any state.

The Round Table 94 World Bank Research Observer 23 1: However, the choice of democracy for post-colonial African states has been rife with controversy. Imposition of democracy can become a violation of fundamental freedoms. Journal of International Studies 37 3: Human Rights Quarterly This is not to deny the fact that bad governance in itself may cause the occurrence of the four crimes of R2P, but to emphasise the fact that good governance and apparent democracy are not synonymous. Ogundiya states that good governance is impossible where democracy is not comprehended by political elite who are unable to achieve the essence of the state.

While governmental actors have enough legitimacy and clout to encourage democracy in states, there has to be adequate research and evaluation of the political culture to ensure that democratization does not cause more problems than it solves by hiding atrocities under a facade of acceptability. The veil of elections has to be lifting to ensure that there produce accountable and equitable sovereign governments.

Fi all a Light at the End of the Tunnel? The international community seems to have investigated thoroughly neither the claims of both the Constitutional Council nor those of the electoral commission before reaching its conclusion. At the beginning of masses of protest swept across North Africa and the Middle East. Protesters in countries such as Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya called for the ousting of their long-reigning autocratic rulers and the entrenchment of democracy.

The protests in North Africa and the Middle East, are examples of internal outcry for democracy, and seem to be a better model for achieving textbook democracy. Secondly the democratic elections as prescribed by the international community and international human rights law have been held; technically the letter of the law has been fulfilled.