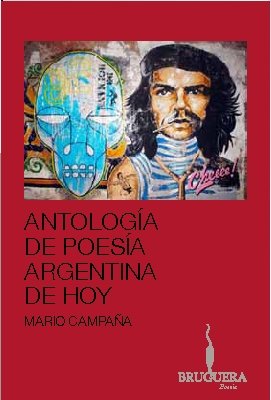

Baudelaire: Juego de triunfos (Spanish Edition)

Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines: Rafael more than three centuries of Spanish rule in 18g8, only about 1 per- cent of the population had any fluency in Castilian. The Philippine colony was located at the furthest edges of the Spanish empire. Even with the opening of the Suez Canal in g, travel to the Philippines from Spain was still a matter of several months. Pos- sessing neither the gold nor the silver of the New World colonies, the Philippines had few attractions for Spanish settlers.

Fearful of repeat- ing the large-scale miscegenation between Spaniards, Indians, and Mricans in the New World, the Crown had established restrictive resi- dency laws discouraging Spanish settlement outside the walls of Manila. As a result, no sizable population of Spanish-speaking creoles or mes- tizos ever emerged. Enforcing existing laws, the government, if it chose to, could devote resources to building schools and providing for the more sys- tematic instruction of Castilian.

Yet the state seemed not only inca- pable but unwilling to carry out these measures. It seemed then to be violating its own laws. Such conditions came about, as ilustrados saw it, largely because of the workings of the Spanish friars. They had long blocked the teaching of Castilian in the interest of guard- ing their own authority. It was their steadfast opposition to the teach- ing of Castilian that kept the colony from progressing.

Cast as fig- ures opposed to modernity, the Spanish clergy became the most significant target of ilustrado enmity. In their inordinate influence over the state and other local practices, the friars were seen to stand in the way of "enlightenment," imagined to consist of extended con- tact and sustained exchanges with the rest of the "civilized" world.

Thanks to the friars, colonial subjects were deprived of a language 8. Government Printing Office, , 2: See Nicholas Cushner, Spain in the Philippines: From Conquest to Revolution Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila Press, To answer this question, one needs to keep in mind the immense significance of Catholic conversion in the conquest and colonization of the Philippines. Spanish missionaries were the most important agents for the spread of colonial rule. Colonial officials came and went, owing their positions to the patronage of politicians and the volatile conditions of the home government.

They often amassed for- tunes during their brief tenure and with rare exceptions remained rel- atively isolated from the non-Spanish populace. By contrast, the Span- ish clergy were stationed in local parishes all over the colony. They retained a corporate identity that superseded the governments of both the colony and the mother country. Indeed, they claimed to be answerable only to their religious superiors and beyond that to a God that transcended all other worldly arrangements.

It was their access to an authority beyond colonial hierarchy that proved essential in con- serving their identity as indispensable agents of Spanish rule. Through the clergy, the Crown validated its claims of benevolent conquest. Colonization was legitimized as the extension of the work of evangelization. Acting as the patron of the Catholic Church, a role it had zealously assumed since the Counter-Reformation, the Crown shared in the task of communicating the Word of God to unknowing natives. While the state relied on the Church to consolidate its hold on the islands, the Church in turn depended on the state in carrying out its task of conversion.

Missionaries depended on the material and monetary support of the state, drawing on colonial courts to secure its landholdings especially in the later nineteenth century , on military forces to put down local uprisings and groups of bandits, and on the institution of forced labor for the building of churches and convents. For another treatment of the place of the friar in the ilustrado imaginary, see Vicente L.

Transloeal Essay in Filipino Cultures, ed.

www.newyorkethnicfood.com: Baudelaire: Juego de triunfos (Spanish Edition) eBook: Mario Campaña: Kindle Store

Ateneo de Manila University, Rafael However, the success of the Spanish missionaries in converting the majority of lowland natives to Catholicism rested less on coercion - it could not, given the small number of Spanish military forces in the islands-as it did on translation. As I have elsewhere discussed at length, evangelization relied on the task of translation. Beginning in the lat- ter sixteenth century, Spanish missionaries, following the practice in the New World, systematically codified native languages. They replaced the local script baybayin with Roman letters, used Latin categories to reconstruct native grammars, and Castilian definitions in constructing dictionaries of the vernaculars.

Catholic teachings were then translated and taught in the local languages. At the same time, the missionary pol- icy insisted on retaining key terms in their original Latin and Castilian forms. Such words as Dios, Espiritu Santo, Virgen, along with the lan- guage of the mass and the sacraments, remained in their un translated forms in Latin and Castilian so as not to be confused, or so the mis- sionaries thought, with pre-Christian beliefs and rituals.

Through the translation of God's Word, natives came to see in Spanish missionaries a foreign presence speaking their "own" lan- guage. As I have demonstrated elsewhere, this appearance-as sud- den as it was unmotivated from the natives' point of view-of the foreign in the familiar and its reverse, the familiar in the foreign- roused native interests and anxieties.

Conversion was thus a matter of responding to this startling-because novel-emergence of alien messages from alien speakers from within one's own speech. It was to identify oneself with this uncanny occurrence and to submit to its attractions, which included access to an unseen yet omnipresent source of all power. Conversion translated the vernacular into another language, con- verting it into a medium for reaching beyond one's own world. Rafael, Contracting Colonialism, esp. He stood at the crossroads of languages, for he spoke not only the vernacular but also Castilian and Latin.

And because of his insistence on retaining untranslated words within the local versions of the Word, he evinced the limits of translation, the points at which words became wholly absorbed and entirely subservient to their referents. The imper- atives of evangelization meant that translation would be at the service of a higher power. Unlike the telegraph cable, which opened up to a potentially limitless series of translations and transmissions, evangeliza- tion encapsulated all languages and messages within a single, ruling Word,Jesus Christ, the incarnate speech of the Father.

Through the missionaries, converts could hope to hear the Word of the Father resonating within their own words. Put differently, Catholic conversion in this colonial context was predicated on the transmission of a hierarchy of languages. Submitting to the Word of the Father, one came to realize that one's first language was subordi- nate to a second, that a foreign because transcendent presence ruled over one's thoughts, and that such thoughts came through a chain of mediations: We can think of the missionary then as a medium for the com- munication of a hierarchy of communications that was thought to frame all social relations.

Through him, native societies were reordered as recipients of a gift they had not expected in the form of a novel message to which they felt compelled to respond. What made the mes- sage compelling was precisely its form. The missionary's power lay in his ability to predicate languages, that is, to conjoin them into a speech that issued from above and was meant to be heard by those below at some predestined time. The power of predication, therefore, also came with the capacity for prediction, that is, the positing of events as the utterance of a divine promise destined to be fulfilled in the future.

To experience language hierarchically unfolding, as for example in prayer or in the sacraments, is to come to believe in the fatality of speech. All messages inevitably reach their destinations, if not now, then in the future. Moreover, they will all be answered, if not in one way then in another. The attractions of conversion thus included the assurance that one always had the right address. Rafael In tracing the linguistic basis of missionary agency, one can begin to understand how it is they became so crucial in legitimating colonial rule and consolidating its hegemony. The rhetoric of conversion and the practice of translation allowed for the naturalization, as it were, of hierarchy, linguistic as well as social.

They made colonization seem both inevitable and desirable. At the same time, one can also appreci- ate the depth of nationalist fascination with the friars and their obses- sive concern with the Spanish fathers' influence over the motherland.

- The Imperative Mood.

- ;

- Trio Sonata in C minor - Op. 1 no. 8.

- Buscando a las Musas Perdidas: La estética de Baudelaire.

- ?

- .

- !

As "sons" of the motherland, the ilustrados wanted to speak in a lan- guage recognizable to colonial authorities. To do so meant assuming the position of the friar, that is, of becoming an agent of translation who could speak up and down the colonial hierarchy, making audible the interests of those at the bottom to those on top.

- Interpretation of Dreams.

- .

- .

- Marrying Minister Right (Mills & Boon Love Inspired) (After the Storm, Book 3)?

- .

It also implied the ability to speak past colonial divisions: It is with these historical matters in mind that we can return to the nationalist demand for the teaching of Castilian. The Risk of Misrecognition Remarking on the royal decrees providing for the teaching of Castil- ian to the natives, a writer for La Solidaridad deplores the failure of authorities to enact these laws.

Buy for others

All the more unfortunate since "the people wish to express their concerns without the intervention of intermediary elements elementos intermediarios. Moreover, in the Philippines, the ability to speak and write in Castilian constitutes a distinction. There, it is embarrassing not to possess it, and in what- ever gathering it is considered unattractive and up to a point shame- ful for one to be in a position of being unable to switch to the official language.

Unlike the Dutch East Indies, for example-where Melayu existed as a common language between colonizer and colo- The cita- tion appears on p.

Product details

Educational reforms that would spread Castilian would eliminate this "shameful" situation. However, as the writer notes, Spanish friars have refused to give up their position. Instead of recognizing the desire of natives to learn Castilian, friars have come to suspect their motives. He or she who advocates the teaching of Castilian are treated as potential "enemies of the country Not only do Spanish fathers stand in the way of direct contact between the people and those who rule them, they misrecognize natives who speak Castilian as subversives and criminals.

While nationalists associ- ate the learning of Castilian with progress and modernity, the Spanish friars see it as a challenge to their authority: For indeed, the word for "subversive," jilibustero, also refers to a pirate, hence to a thief. Blocked from disseminating Castilian, nationalists also become suspect.

Rather than accept the position laid out for them as "natives," they insist on speaking as if they were other, and thus foreign to colo- nial society. For the history of Melayu, see HenkJ. Maier, "From Heteroglossia to Polyglossia: Princeton Uni- versity Press, My understanding of the history of the language of nationalism in the Philippines has been influenced not only by the ways it seems to have differed from the history of the Indonesian language but also by the ways in which such dif- ferences have produced at certain moments instructive similarities.

Cornell University Press, , have been indispensable guides for thinking through the top- ics of language and politics in the Philippine case.

Cited in Schu- macher, Making of a Nation, It is not they who are criminals, but the friars who accuse them. Over and over again, writers for La Solidaridad refer to friars as "unpatriotic Spaniards," hence the real filibusteros. In an article not atypical in tone and content, one writer asks: In fact who is the friar? Somebody egoistic, avaricious, greedy They have been assassins, poisoners, liars, agitators of public peace Look at the true picture of those great men From their perspective, the friars are subversives who stand in the way of a happier union between the colonial state and its subjects.

Yet neither the state nor the Church recognizes this fact. Authorities won't listen, or more precisely, they mishear, mistaking the ilustrado desire for Span- ish as his or her rejection of Spain. The delirious enumeration of cler- ical criminality in the passage above reflects something of a hysterical response to repeated miscommunications. Such alarm is understand- able, given the grave consequences of being misheard in the way of imprisonment and executions.

What is clear is that having a common language does not guaran- tee mutual understanding, but the reverse. Castilian in this instance is a shared language between colonizer and colonized. Yet the result is not the closer union that nationalists had hoped for, but mutual mis- recognition. Each imagines the other to be saying more than they had intended to. Acting on each other's misconceptions, they come to exchange positions in one another's minds.

Questions about language lead to suspicions, conflict, and violence. Rather than reconcile the Historically, as we have seen, it was the Spanish friars who had monopolized the ability of the self to speak in the language of the other, controlling the terms of translation by invoking a divinely sanc- tioned linguistic hierarchy. Conversion occurred to the extent that natives could read into missionary discourse the possibility of being recognized by a third term that resided beyond both the missionary and the native.

But by the late nineteenth century, this situation had been almost reversed. Nationalists addressed Spaniards in the latter's own language. The friars did not see in Spanish-speaking natives a mirror reflection of themselves. For after all, given the racial logic of colonialism, how could the native be the equivalent of the European? Rather, friars tended to see nationalists as filibusteros guilty of stealing what rightfully belongs to them and compromising their position as the privileged media of colonial communication.

In their eyes, nation- alists were speaking out of turn. Their Castilian had no authority inas- much as it was uttered outside hierarchy. From the friars' perspective then, nationalist attempts to translate their interests into a second lan- guage only placed them outside the linguistic order of colonial society. Thus were nationalists rendered foreign. Speaking Castilian they appeared to be other than mere natives and therefore suspect in the eyes of Spanish fathers. Speaking Castilian produced strange and disconcerting effects. For nationalists, Castilian was supposed to be the route to modernity.

Progress came, so they thought, in gaining access to the means with which to communicate directly with authorities and with others in the world. It followed that Castilian was a means ofleaving behind all that was "backward" and "superstitious," that is, all that came under the influence of the friars.

To learn Castilian was to exit the existing order of oppression and enter into a new more "civilized" world of equal representation. Castilian in this sense was a key that allowed one to move within and outside colonial hierarchy. Nonetheless, such movements came with certain risks. Speak- ing Castilian, one faced the danger of being misrecognized. We saw this possibility in the vexed relationship between nationalists and colonial authorities i. Rafael tion, however, also carried over into Spain. Seeking to escape perse- cution, nationalists often fled abroad.

Most gravitated to Barcelona and Madrid, which became centers of nationalist agitation in the s to the midS. In these cities, Filipinos found themselves reaching a sympathetic audience among Spanish liberals and other Europeans. Their writings were given space in Spanish liberal newspa- pers. In Madrid and Paris, Filipino artists such asJuan Luna and Felix Resurrection Hidalgo won a string of prizes painting in the academic style of the period, which one might think of as speaking a kind of Castilian. And in the pages of La Solidaridad, one reads of political banquets where nationalists addressed Spanish audiences and were greeted with approval and applause.

Castilian seemed to promise a way out of colonial hierarchy and a way into metropolitan society. However, in other nationalist accounts we also see how this promise fails to materialize. Nationalists find themselves betrayed by Castilian in both senses of the word. Out of this betrayal, other responses arise, including phantasms of revenge and revolution. It is to these successes and failures of translation and recognition and the responses they incur that I now wish to turn. The Limits ofAssimilation Reading once again the newspaper La Solidaridad, we get a sense of the attractions that Castilian and Spain held for Filipino nationalists.

An instructive example is the speech delivered in by Graciano Lopez- Jaena, one of paper's editors, during a political banquet in Barcelona. I7 He begins with a declaration of his own foreignness. He announces to the Spanish audience that he is "of little worth, accompanied by an obscure name, totally unknown and foreign to you, with a face show- ing a country different from your generous land, a race distinct from yours, a language different than yours, whose accent betrays me" That is, he comes before an audience and tells them in their language that "I am not you.

Jaena calls attention to the dif- ference of his appearance, aligning it with his accented Spanish, which Be indulgent toward me. Here, the native addresses the other in the latter's language. He appears as someone acutely conscious of his difference from those he addresses. The audience hears and responds with approval.

In this way, the native not only maps the gap between himself and the other; more important, he succeeds in crossing it. Tra- versing racial and linguistic differences, his "I" is able to float free from its origins and appear before a different audience. When the audience responds with a murmur of approval, it identifies not with the speaker but with his ability to be otherwise. The audience comes to recognize the native's ability to translate: The native defers to his audience-"I am nobody"-and that deference, heard in the language of the audience, meets with approval.

Recognized in his ability to get across, to keep his audience in mind, and to know his place in relation to theirs, the native can con- tinue to speak, now with the confidence of being able to connect. The contents of Lopez: Jaena's speech are themselves unremark- able and predictable. The speech contains the usual call for reforms- economic, political, and educational-that would lead to the improve- ment of the colony.

It extols the riches of the archipelago while lamenting the state's inability to make better use of them. And it invariably identifies the friar orders as the source of resistance to change in the colony. Finally, it calls on Spain to rid the colony of friars and devote attention to the development of commercial opportuni- ties in the Philippines and to the needs of its inhabitants. What is worth noting is the reception he gets.

As it appears in the printed version, the speech is punctuated by the sound of applause ranging from "mild and approving" to "prolonged and thunderous," particularly when he lauds Spanish war efforts in repulsing German attempts to seize Spain's Pacific island possessions. By the end of the speech, the audience explodes with "frenzied, prolonged applause, bravos, enthusiastic and noisy ovations, congratulations, and embraces given to the orator" Rafael In the course of his speech, Lopez: Jaena goes through a signifi- cant transformation.

He starts out an obscure foreigner, but by the lat- ter half of his speech, he begins to refer to himself as a Spaniard. In criticizing the ineptitude of the colonial state and denouncing the ill effects of the friars, he says, "There are efforts to hide the truth. From being a mere native, a "nobody," "I" am now a Spaniard like "you.

Using a language not his own, Lopez: Castilian in this case allows for what appears to be a successful transmission of messages, of which there are at least two: We can understand the fren- zied applause at the end of the speech as a way of registering this event. That a foreigner appears, proclaims his difference from and deference to his hosts in their own language, thereby crossing those gaps opened up by his presence; that an audience forms around his appearance, seeing in him one who bears a message, and recognizes his ability to become other than what he had originally claimed to be: It is the materialization of the fantasy of arriving at a common language that has the power to take one beyond hierarchy.

Although it begins with an acknowledgment of inequality, Castilian as a lingua franca allows one to set hierarchy aside. To become a "patriot" is thus inseparable from being recog- nized by others as one who is a carrier of messages and is therefore a medium of communication. It is to embody the power of translation.

What happens, though, when there is no applause, or when the applause is deferred? What becomes of the movement from a native "I" to a Spanish "I" when the sources of recognition are unknown or uncertain? Outside the banquet, such questions arose to confront nationalists in the streets of the metropole. We can see this, for exam- ple, in the travel writings of Antonio Luna. La Solidaridad regularly featured the travel accounts of Luna, who would later become one of the most feared generals of the Philippine revolutionary army in the war against Spain and would subsequently be enshrined as part of the pantheon of national heroes by the Repub- From The Places of History by Sommer, Doris.

As a student in Paris, he visited the Exposition of and under the pseudonym 'Taga-ilog" a pun on the word Tagalog, which literally means from the river , wrote of his impressions. He was fascinated by the exhibits from other European colonial possessions but felt acutely disappointed that the Philippine exhibit was poorly done.

In one arti- cle, he praises the exhibits from the French colonies. He is particularly envious of the displays from Tonkin, which show the regime's attempts at assimilating the natives through the teaching of French. Such exam- ples bring to mind Spanish refusal to spread its language in the Philip- pines. By comparison to those in the French colonies, ''We Filipinos nosotros filipinos are in a fetal and fatal condition. But we, Spaniards nosotros espafioles do not want to follow this path It behooves this race of ours-this race of famous ancestors, giants, and heroes-to think of greater things.

Our Filipinos already know the most intricate declensions of classic Latin; never mind if they do not understand a word of Castilian. And then in the next paragraph: We who had the fortune of receiving in those beautiful regions of the Philippines the first kiss oflife Later in that town, isolated from all cul- tures, we saw among 14, inhabitants a teacher without a degree, a priest who alone knew Castilian, a town with one deplorable school without equipment for teaching and without students. IS There are at least three references invoked by the pronoun "we" nosotros in the passages above: What triggers this switch from one referent to another is the embarrassment and disappointment Luna feels in seeing the Philippine exhibit.

Its crudeness and inadequacy become suddenly apparent when compared with the French exhibit. Rafael him to think of the latter as somehow superior in that it reveals what is lacking in the former. In this sense, we might think of "French" as that which encapsulates "Castilian. The invocation of "French" seems here to have the effect of joining the colonizer to the colonized in the Philippines, implied by the rapid changes of registers in Luna's ''we.

Here, a different kind of assimilation is at work, one that con- trasts with the banquet scene. The audience in Lopezjaena's case responded to his speech and took note of his capacity to distinguish, then suture, differences. In Luna's case, the slide from "Filipino" to "Spaniard" and back is provoked by embarrassment, not applause. He sees the Philippine exhibit and imagines others seeing it, then com- paring it to the French, as he does. He thus becomes aware of another ''we," an unmarked and anonymous presence who wanders into the exhibits and sees him looking.

He is of course also part of that anony- mous ''we," who we could think of as the crowd. A crowd by definition is something that exists outside oneself. To become part of a crowd is to feel oneself as other. Siegel writes, 'The crowd One becomes like it and unlike oneself and one does so precisely by responding to it. Becoming alien to oneself and replying He finds himself not only split between "Filipino" and "Spaniard" but also between one who sees and one who is seen.

Castilian addressed to Spaniards allowed Lopezjaena to reconceive hierarchy and set it aside, even if only momentarily. In Luna's case, however, Castilian spoken, even to oneself amid a crowd, only produces a redoubling of his alienation. Assimilation occurs without recognition. He finds himself to be where he is not: Recognition fails him as he shuttles between identifications, unable to consolidate either one. One can translate, be understood by the other, yet find oneself unrecognized. Luna's dilemma in Paris becomes even more pro- Siegel, Fetish, Recognition, and Revolution, In one essay, he reports the follow- ing exchange with a Spanish woman: I am surprised that you speak it much as I do to posea tanto ramo yo.

Spanish is spoken in your country? Perhaps we are thought to be little less than savages or Igorotes; perhaps they ignore the fact that we can communicate in the same lan- guage, that we are also Spaniards, that we should have the same privileges since we have the same duties. Rather than arrive at its intended address, his message-that yes, "I," too, am a Spaniard; that "I" am not a savage-has been lost.

The self that speaks Castilian cannot get across.

No customer reviews

The native finds himself stranded in that "ahhh!!! Would you like to tell us about a lower price? Read more Read less. Thousands of books are eligible, including current and former best sellers. Look for the Kindle MatchBook icon on print and Kindle book detail pages of qualifying books. Print edition must be purchased new and sold by Amazon. Gifting of the Kindle edition at the Kindle MatchBook price is not available. Learn more about Kindle MatchBook. Kindle Cloud Reader Read instantly in your browser. Product details File Size: February 4, Sold by: Not Enabled Screen Reader: Enabled Amazon Best Sellers Rank: Share your thoughts with other customers.

Write a customer review. Amazon Giveaway allows you to run promotional giveaways in order to create buzz, reward your audience, and attract new followers and customers. Learn more about Amazon Giveaway. Juego de triunfos Spanish Edition. Set up a giveaway. There's a problem loading this menu right now. Learn more about Amazon Prime.