Irish Epic Poem in 33 Cantos

Lawrence to reposition his view, and entertain the possibility that certain elements in the saga such as the waterfall in place of the mere retained an older form. The viability of this connection has enjoyed enduring support, and was characterized as one of the few Scandinavian analogues to receive a general consensus of potential connection by Theodore M. Another candidate for a cogener analogue or possible source is the story of Hrolf kraki and his servant, the legendary bear- shapeshifter Bodvar Bjarki.

Hence a story about him and his followers may have developed as early as the 6th century. This tale type was later catalogued as international folktale type , now formally entitled "The Three Stolen Princesses" type in Hans Uther 's catalogue, although the "Bear's Son" is still used in Beowulf criticism, if not so much in folkloristic circles. However, although this folkloristic approach was seen as a step in the right direction, "The Bear's Son" tale has later been regarded by many as not a close enough parallel to be a viable choice.

For no such correspondence could be perceived in the Bear's Son Tale or Grettis saga. Attempts to find classical or Late Latin influence or analogue in Beowulf are almost exclusively linked with Homer 's Odyssey or Virgil 's Aeneid. In , Albert S. Cook suggested a Homeric connection due to equivalent formulas, metonymies , and analogous voyages. Work also supported the Homeric influence, stating that encounter between Beowulf and Unferth was parallel to the encounter between Odysseus and Euryalus in Books 7—8 of the Odyssey, even to the point of both characters giving the hero the same gift of a sword upon being proven wrong in their initial assessment of the hero's prowess.

This theory of Homer's influence on Beowulf remained very prevalent in the s, but started to die out in the following decade when a handful of critics stated that the two works were merely "comparative literature", [] although Greek was known in late 7th century England: Several English scholars and churchmen are described by Bede as being fluent in Greek due to being taught by him; Bede claims to be fluent in Greek himself. Frederick Klaeber , among others, argued for a connection between Beowulf and Virgil near the start of the 20th century, claiming that the very act of writing a secular epic in a Germanic world represents Virgilian influence.

Virgil was seen as the pinnacle of Latin literature, and Latin was the dominant literary language of England at the time, therefore making Virgilian influence highly likely. It cannot be denied that Biblical parallels occur in the text, whether seen as a pagan work with "Christian colouring" added by scribes or as a "Christian historical novel, with selected bits of paganism deliberately laid on as 'local colour'," as Margaret E.

Goldsmith did in "The Christian Theme of Beowulf ".

- ?

- Porto (GUIDE DE VOYAGE) (French Edition).

- The Book of Jubilees.

There is a wide array of linguistic forms in the Beowulf manuscript. It is this fact that leads some scholars to believe that Beowulf has endured a long and complicated transmission through all the main dialect areas. Considerably more than one-third of the total vocabulary is alien from ordinary prose use. There are, in round numbers, three hundred and sixty uncompounded verbs in Beowulf , and forty of them are poetical words in the sense that they are unrecorded or rare in the existing prose writings.

One hundred and fifty more occur with the prefix ge - reckoning a few found only in the past-participle , but of these one hundred occur also as simple verbs, and the prefix is employed to render a shade of meaning which was perfectly known and thoroughly familiar except in the latest Anglo-Saxon period. The nouns number sixteen hundred. Seven hundred of them, including those formed with prefixes, of which fifty or considerably more than half have ge -, are simple nouns, at the highest reckoning not more than one-quarter is absent in prose.

That this is due in some degree to accident is clear from the character of the words, and from the fact that several reappear and are common after the Norman Conquest. An Old English poem such as Beowulf is very different from modern poetry. Anglo-Saxon poets typically used alliterative verse , a form of verse in which the first half of the line the a-verse is linked to the second half the b-verse through similarity in initial sound. In addition, the two halves are divided by a caesura: This verse form maps stressed and unstressed syllables onto abstract entities known as metrical positions.

There is no fixed number of beats per line: The poet has a choice of epithets or formulae to use in order to fulfil the alliteration. When speaking or reading Old English poetry, it is important to remember for alliterative purposes that many of the letters are not pronounced in the same way as in modern English. Both are voiced as in this between other voiced sounds: Otherwise they are unvoiced as in thing: Kennings are also a significant technique in Beowulf.

They are evocative poetic descriptions of everyday things, often created to fill the alliterative requirements of the metre. For example, a poet might call the sea the "swan-road" or the "whale-road"; a king might be called a "ring-giver. The poem also makes extensive use of elided metaphors. Tolkien argued in Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics that the poem is not an epic, and while no conventional term exactly fits, the nearest would be elegy. The history of modern Beowulf criticism is often said to begin with J. Tolkien , [] author and Merton professor of Anglo-Saxon at University of Oxford , who in his lecture to the British Academy criticised his contemporaries' excessive interest in its historical implications.

The Monsters and the Critics that as a result the poem's literary value had been largely overlooked and argued that the poem "is in fact so interesting as poetry, in places poetry so powerful, that this quite overshadows the historical content In historical terms, the poem's characters would have been Norse pagans the historical events of the poem took place before the Christianisation of Scandinavia , yet the poem was recorded by Christian Anglo-Saxons who had mostly converted from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism around the 7th century — both Anglo-Saxon paganism and Norse paganism share a common origin as both are forms of Germanic paganism.

Beowulf thus depicts a Germanic warrior society , in which the relationship between the lord of the region and those who served under him was of paramount importance. In terms of the relationship between characters in Beowulf to God, one might recall the substantial amount of paganism that is present throughout the work. Literary critics such as Fred C. Robinson argue that the Beowulf poet arguably tries to send a message to readers during the Anglo-Saxon time period regarding the state of Christianity in their own time.

Robinson argues that the intensified religious aspects of the Anglo-Saxon period inherently shape the way in which the Poet alludes to paganism as presented in Beowulf. The Poet arguably calls on Anglo-Saxon readers to recognize the imperfect aspects of their supposed Christian lifestyles. In other words, the Poet is referencing their "Anglo-Saxon Heathenism. But one is ultimately left to feel sorry for both men as they are fully detached from supposed "Christian truth" The relationship between the characters of Beowulf , and the overall message of the Poet, regarding their relationship with God is largely debated among readers and literary critics alike.

At the same time, Richard North argues that the Beowulf poet interpreted "Danish myths in Christian form" as the poem would have served as a form of entertainment for a Christian audience , and states: This question is pressing, given Other scholars disagree, however, as to the meaning and nature of the poem: The question suggests that the conversion from the Germanic pagan beliefs to Christian ones was a prolonged and gradual process over several centuries, and it remains unclear the ultimate nature of the poem's message in respect to religious belief at the time it was written. Yeager notes the facts that form the basis for these questions:.

That the scribes of Cotton Vitellius A.

XV were Christian beyond doubt, and it is equally sure that Beowulf was composed in a Christianised England since conversion took place in the sixth and seventh centuries. The poem is set in pagan times, and none of the characters is demonstrably Christian. In fact, when we are told what anyone in the poem believes, we learn that they are pagans.

Beowulf's own beliefs are not expressed explicitly. He offers eloquent prayers to a higher power, addressing himself to the "Father Almighty" or the "Wielder of All. Or, did the poem's author intend to see Beowulf as a Christian Ur-hero, symbolically refulgent with Christian virtues? The location of the composition of the poem is also intensely disputed. Moorman , the first professor of English Language at University of Leeds , claimed that Beowulf was composed in Yorkshire, [] but E.

Talbot Donaldson claims that it was probably composed more than twelve hundred years ago, during the first half of the eighth century, and that the writer was a native of what was then called West Mercia, located in the Western Midlands of England. However, the late tenth-century manuscript "which alone preserves the poem" originated in the kingdom of the West Saxons — as it is more commonly known. Greenfield has suggested that references to the human body throughout Beowulf emphasise the relative position of thanes to their lord.

He argues that the term "shoulder-companion" could refer to both a physical arm as well as a thane Aeschere who was very valuable to his lord Hrothgar. With Aeschere's death, Hrothgar turns to Beowulf as his new "arm. Daniel Podgorski has argued that the work is best understood as an examination of inter-generational vengeance-based conflict, or feuding.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. This article is about the epic story. For the character, see Beowulf hero. For other uses, see Beowulf disambiguation. Old English epic story. List of translations and artistic depictions of Beowulf. Kentish Mercian Northumbrian West Saxon. Old English sources hinges on the hypothesis that Genesis A predates Beowulf.

- Maple Grove Cemetery (Images of America).

- ;

- Audioboom / Irish Epic Poem in 33 Cantos ().

- .

- !

- .

- Audioboom / Irish Epic Poem in 33 Cantos: Canto 16 - read by the poet #epicpoem;

- .

- .

- A Rose for Emily William Faulkner: A Critical Analysis?

- Mamas Glücksbuch: Der Begleiter für gelassene Mütter (German Edition);

- ?

He suggested the Irish Feast of Bricriu which is not a folktale as a source for Beowulf —a theory that was soon denied by Oscar Olson. Introducing English Medieval Book History: Manuscripts, their Producers and their Readers. Retrieved 6 October The dating of Beowulf.

Det svenska rikets uppkomst. In the Heroic Age 5. Retrieved 1 October Gamla Uppsala, Svenska kulturminnen 59 in Swedish. Retrieved 23 October The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. A Reassessment ", Choice Reviews Online , 52 6: A Reassessment , Cambridge: The Singer of Tales, Volume 1. The Monsters and the Critics. Three Issues Bearing on Poetic Chronology". Journal of English and Germanic Philology. Retrieved 30 May Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript 1 ed. Retrieved October 6, Retrieved 19 November Retrieved 14 September Brown University Press, pp.

Harvard University Press, pp. Oral-Formulaic Theory and Research: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography.

Navigation menu

Yale University Press, p. History and Methodology , Bloomington: Preface to Plato, Cambridge, MA: Altenglische Dichtung zwischen Muendlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Retrieved 19 April Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. Archived from the original on 21 November Retrieved 21 November Revival and Re-Use in the s". The Review of English Studies. Journal of Irish Studies 2: Retrieved 21 March Tolkien's 'Beowulf ' ". Retrieved 2 June Retrieved 25 July The long arm of coincidence: University of Toronto Press.

University of Nebraska Press, Retrieved 18 January The Norton Anthology of English Literature 8th ed. In Fulk, Robert Dennis. Retrieved 17 August National Endowment For The Humanities. Retrieved 2 October Retrieved 13 February University of Nebraska Press, pp. Indiana University Press, pp. Heaney, Seamus , Beowulf: A New Verse Translation , W. Beowulf Told to the Children of the English Race, — Beowulf and the English Literary Tradition" , Ragazine.

Nicholson, Lewis E, ed. North, Richard , "The King's Soul: Danish Mythology in Beowulf", Origins of Beowulf: From Vergil to Wiglaf , Oxford: DS Brewer ——— b , Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript , Toronto: Beck , and II. Sigfrid in German Puhvel, Martin Beowulf and the Celtic Tradition. Cambridge University Press, p. Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel [].

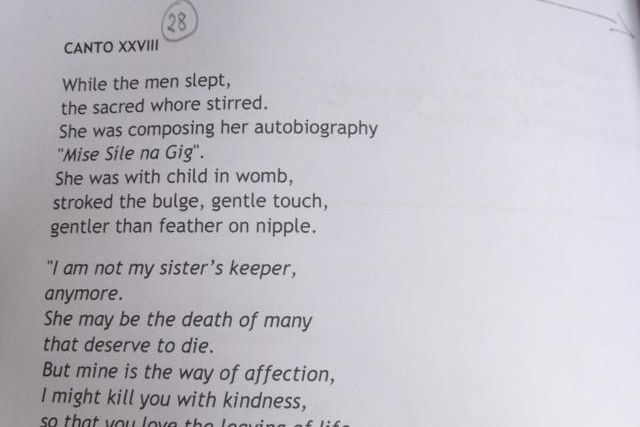

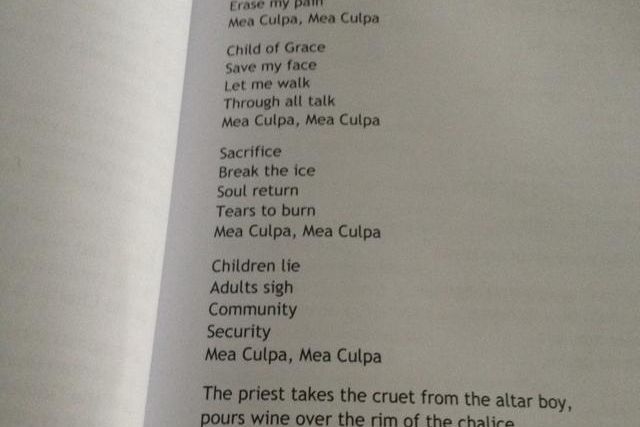

The Monsters and the Critics and other essays. Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel Trask, Richard M , "Preface to the Poems: Epic Companions", Beowulf and Judith: The major locus of these cantos is the city of Venice. The rest of the canto is concerned with Venice, which is portrayed as a stone forest growing out of the water. Canto XIX deals mainly with those who profit from war, returning briefly to the Russian Revolution, and ends on the stupidity of wars and those who promote them.

These fragments constellate to form an exemplum of what Pound calls "clear song". There follows another exemplum, this time of the linguistic scholarship that enables us to read these old poetries and the specific attention to words this study requires. Finally, this "clear song" and intellectual activity is implicitly contrasted with the inertia and indolence of the lotus eaters , whose song completes the canto.

There are references to the Malatesta family and to Borso d'Este , who tried to keep the peace between the warring Italian city states. These are contrasted with the actions of Thomas Jefferson , who is shown as a cultured leader with an interest in the arts. A phrase from one of Sigismondo Pandolfo's letters inserted into the Jefferson passage draws an explicit parallel between the two men, a theme that is to recur later in the poem.

The next canto continues the focus on finance by introducing the Social Credit theories of C. Douglas for the first time. Anecdotes on Titian and Mozart deal with the relationship between artist and patron. The last two cantos in the series return to the world of "clear song". Finally, the series closes with a glimpse of the printer Hieronymus Soncinus of Fano preparing to print the works of Petrarch.

Canto XXXI opens with the Malatesta family motto Tempus loquendi, tempus tacendi "a time to speak, a time to be silent" to link again Jefferson and Sigismondo as individuals and the Italian and American "rebirths" as historical movements. Canto XXXV contrasts the dynamism of Revolutionary America with the "general indefinite wobble" of the decaying aristocratic society of Mitteleuropa. This canto contains some distinctly unpleasant expressions of antisemitic opinions.

This poem, a lyric meditation of the nature and philosophy of love, was a touchstone text for Pound. The canto then closes with the figure of the 9th-century Irish philosopher and poet John Scotus Eriugena , who was an influence on the Cathars and whose writings were condemned as heretical in both the 11th and 13th centuries. The canto then turns to modern commerce and the arms trade and introduces Frobenius as "the man who made the tempest". There is also a passage on Douglas' account of the problem of purchasing power.

Canto XXXIX returns to the island of Circe and the events before the voyage undertaken in the first canto unfolds as a hymn to natural fertility and ritual sex. Canto XL opens with Adam Smith on trade as a conspiracy against the general public, followed by another periplus , a condensed version of Hanno the Navigator 's account of his voyage along the west coast of Africa. The book closes with an account of Benito Mussolini as a man of action and another lament on the waste of war. Founded in , the Monte dei Paschi was a low-interest, not-for-profit credit institution whose funds were based on local productivity as represented by the natural increase generated by the grazing of sheep on community land the "BANK of the grassland" of Canto XLIII.

As such, it represents a Poundian non-capitalist ideal. Canto XLV is a litany against Usura or usury , which Pound later defined as a charge on credit regardless of potential or actual production and the creation of wealth ex nihilo by a bank to the benefit of its shareholders. The canto declares this practice as both contrary to the laws of nature and inimical to the production of good art and culture. Pound later came to see this canto as a key central point in the poem. Canto XLVI contrasts what has gone before with the practices of institutions such as the Bank of England that are designed to exploit the issuing of credit to make profits, thereby, in Pound's view, contributing to poverty, social deprivation, crime and the production of "bad" art as exemplified by the baroque.

There follows a long lyrical passage in which a ritual of floating votive candles on the bay at Rapallo near Pound's home every July merges with the cognate myths of Tammuz and Adonis , agricultural activity set in a calendar based on natural cycles, and fertility rituals. The canto then moves via Montsegur to the village of St-Bertrand-de-Comminges, which stands on the site of the ancient city of Lugdunum Convenarum. The destruction of this city represents, for the poet, the treatment of civilisation by those he considers barbarous. Canto XLIX is a poem of tranquil nature derived from a Chinese picture book that Pound's parents brought with them when they retired to Rapallo.

Canto L, which again contains antisemitic statements, moves from John Adams to the failure of the Medici bank and more general images of European decay since the time of Napoleon I. The final canto in this sequence returns to the usura litany of Canto XLV, followed by detailed instructions on making flies for fishing man in harmony with nature and ends with a reference to the anti-Venetian League of Cambrai and the first Chinese written characters to appear in the poem, representing the Rectification of Names from the Analects of Confucius the ideogram representing honesty at the end of Canto XLI was added when The Cantos was published as a single volume.

These eleven cantos are based on the first eleven volumes [ clarification needed ] of the twelve-volume Histoire generale de la Chine by Joseph-Anna-Marie de Moyriac de Mailla. De Mailla was a French Jesuit who spent 37 years in Peking and wrote his history there.

The work was completed in but not published until — De Mailla was very much an Enlightenment figure and his view of Chinese history reflects this; he found Confucian political philosophy, with its emphasis on rational order, much to his liking. He also disliked what he saw as the superstitious pseudo-mysticism promulgated by both Buddhists and Taoists , to the detriment of rational politics. Pound, in turn, fitted de Mailla's take on China into his own views on Christianity, the need for strong leadership to address 20th-century fiscal and cultural problems, and his support of Mussolini.

In an introductory note to the section, Pound is at pains to point out that the ideograms and other fragments of foreign-language text incorporated in The Cantos should not put the reader off, as they serve to underline things that are in the English text. Canto LII opens with references to Duke Leopoldo, John Adams and Gertrude Bell , before sliding into a particularly virulent antisemitic passage, directed mainly at the Rothschild family. The remainder of the canto is concerned with the classic Chinese text known as the Li Ki or Classic of Rites , especially those parts that deal with agriculture and natural increase.

The diction is the same as that used in earlier cantos on similar subjects. Special mention is made of emperors that Confucius approved of and the sage's interest in cultural matters is stressed. For example, we are told that he edited the Book of Odes , cutting it from to poems.

The canto also ascribes the Poundian motto and title of a collection of essays Make it New to the emperor Tching Tang. There is a lot on money policy in this canto and Pound quotes approvingly the Tartar ruler Oulo who noted that the people "cannot eat jewels". This canto is mainly concerned with Genghis and Kublai Khan and the rise of their Yuan dynasty. The canto closes with the overthrow of the Yeun and the establishment of the Ming dynasty , bringing us to around Canto LVII opens with the story of the flight of the emperor Kien Ouen Ti in or and continues with the history of the Ming up to the middle of the 16th century.

Canto LVIII opens with a condensed history of Japan from the legendary first emperor, Emperor Jimmu , who supposedly ruled in the 7th century BCE, to the lateth-century Toyotomi Hideyoshi anglicised by Pound as Messier Undertree , who issued edicts against Christianity and raided Korea , thus putting pressure on China's eastern borders.

The canto then goes on to outline the concurrent pressure placed on the western borders by activities associated with the great Tartar horse fairs, leading to the rise of the Manchu dynasty. Canto LX deals with the activities of the Jesuits, who, we are told, introduced astronomy , western music, physics and the use of quinine.

The canto ends with limitations being placed on Christians, who had come to be seen as enemies of the state. Yong Tching is shown banning Christianity as "immoral" and "seeking to uproot Kung's laws". He also established just prices for foodstuffs, bringing us back to the ideas of Social Credit. There are also references to the Italian Risorgimento , John Adams, and Dom Metello de Souza , who gained some measure of relief for the Jesuit mission. This section of the cantos is, for the most part, made up of fragmentary citations from the writings of John Adams.

Pound's intentions appear to be to show Adams as an example of the rational Enlightenment leader, thereby continuing the primary theme of the preceding China Cantos sequence, which these cantos also follow from chronologically. Adams is depicted as a well-rounded figure; he is a strong leader with interests in political, legal and cultural matters in much the same way that Malatesta and Mussolini are portrayed elsewhere in the poem. The English jurist Sir Edward Coke , who is an important figure in some later cantos, first appears in this section of the poem. Given the fragmentary nature of the citations used, these cantos can be quite difficult to follow for the reader with no knowledge of the history of the United States in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The rest of the canto is concerned with events leading up to the revolution, Adams' time in France, and the formation of Washington's administration. Alexander Hamilton reappears, again cast as the villain of the piece. The word is used of Odysseus in the fourth line of the Odyssey: The next canto, Canto LXIII, is concerned with Adams' career as a lawyer and especially his reports of the legal arguments presented by James Otis in the Writs of Assistance case and their importance in the build-up to the revolution.

The Latin phrase Eripuit caelo fulmen "He snatched the thunderbolt from heaven" is taken from an inscription on a bust of Benjamin Franklin. It also shows Adams defending the accused in the Boston Massacre and engaging in agricultural experiments to ascertain the suitability of Old-World crops for American conditions. The phrases Cumis ego oculis meis , tu theleis , respondebat illa and apothanein are from the passage taken from Petronius ' Satyricon that T.

Eliot used as epigraph to The Waste Land at Pound's suggestion. The passage translates as "For with my own eyes I saw the Sibyl hanging in a jar at Cumae, and when the boys said to her, 'Sibyl, what do you want? The canto shows Adams concerned with the practicalities of waging war, particularly of establishing a navy. Following a passage on the drafting of the Declaration of Independence , the canto returns to Adams' mission to France, focusing on his dealings with the American legation in that country, consisting of Franklin, Silas Deane and Edward Bancroft and with the French foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes.

Intertwined with this is the fight to save the rights of Americans to fish the Atlantic coastline.

Audioboom uses Javascript

A passage on Adams' opposition to American involvement in European wars is highlighted, echoing Pound's position on his own times. The body of the canto consists of quotations from Adams' writings on the legal basis for the Revolution, including citations from Magna Carta and Coke and on the importance of trial by jury per pares et legem terrae. The rest of the canto is concerned with the study of government and with the requirements of the franchise. The following canto, LXVIII, begins with a meditation on the tripartite division of society into the one, the few and the many.

A parallel is drawn between Adams and Lycurgus , the just king of Sparta. Then the canto returns to Adams' notes on the practicalities of funding the war and the negotiation of a loan from the Dutch. Canto LXIX continues the subject of the Dutch loan and then turns to Adams' fear of the emergence of a native aristocracy in America, as noted in his remark that Jefferson feared rule by "the one" monarch or dictator , while he, Adams, feared "the few".

The remainder of the canto is concerned with Hamilton, James Madison and the affair of the assumption of debt certificates by Congress which resulted in a significant shift of economic power to the federal government from the individual states. Canto LXX deals mainly with Adams' time as vice-president and president, focusing on his statement "I am for balance", highlighted in the text by the addition of the ideogram for balance.

The section ends with Canto LXXI, which summarises many of the themes of the foregoing cantos and adds material on Adams' relationship with Native Americans and their treatment by the British during the Indian Wars. The canto closes with the opening lines of Epictetus ' Hymn of Cleanthus , which Pound tells us formed part of Adams' paideuma. These lines invoke Zeus as one "who rules by law", a clear parallel to the Adams presented by Pound. These two cantos, written in Italian, were not collected until their posthumous inclusion in the revision of the complete text of the poem.

Pound reverts to the model of Dante 's Divine Comedy and casts himself as conversing with ghosts from Italy's remote and recent past. Guido Cavalcanti appears on horseback to tell Pound about a heroic deed of a girl from Rimini who led a troop of Canadian soldiers to a mined field and died with the "enemy". This was a propaganda story featured in Italian newspapers in October ; Pound was interested in it because of the connection with Sigismondo Malatesta's Rimini. Both cantos end on a positive and optimistic note, [15] untypical of Pound, and are unusually straightforward. Italian scholars have been intrigued by Pound's idiosyncratic recreation of the poetry of Dante and Cavalcanti.

For example, Furio Brugnolo of the University of Padua claims that these cantos are "the only notable example of epic poetry in 20th-century Italian literature". With the outbreak of war in , Pound was in Italy, where he remained, despite a request for repatriation he made after Pearl Harbor. During this period, his main source of income was a series of radio broadcasts he made on Rome Radio. He used these broadcasts to express his full range of opinions on culture, politics and economics, including his opposition to American involvement in a European war and his antisemitism.

In , he was indicted for treason in absence, and wrote a letter to the indicting judge in which he claimed the right to freedom of speech in his defence. Here he was held in a specially reinforced cage, initially sleeping on the ground in the open air. After three weeks, he had a breakdown that resulted in his being given a cot and pup tent in the medical compound. Here he gained access to a typewriter. For reading matter, he had a regulation-issue Bible along with three books he was allowed to bring in as his own "religious" texts: The only other thing he brought with him was a eucalyptus pip.

Throughout the Pisan sequence, Pound repeatedly likens the camp to Francesco del Cossa 's March fresco depicting men working at a grape arbour. With his political certainties collapsing around him and his library inaccessible, Pound turned inward for his materials and much of the Pisan sequence is concerned with memory, especially of his years in London and Paris and of the writers and artists he knew in those cities.

There is also a deepening of the ecological concerns of the poem. However, The Pisan Cantos is generally the most admired and read section of the work. It is also among the most influential, having affected poets as different as H. Canto LXXIV immediately introduces the reader to the method used in the Pisan Cantos, which is one of interweaving themes somewhat in the manner of a fugue. These themes pick up on many of the concerns of the earlier cantos and frequently run across sections of the Pisan sequence. This canto begins with Pound looking out of the DTC at peasants working in the fields nearby and reflecting on the news of the death of Mussolini, "hung by the heels".

This figure blends into the Australian rain god Wuluwaid , who had his mouth closed up by his father was deprived of freedom of speech because he "created too many things". He, in turn, becomes the Chinese Ouan Jin , or "man with an education". This theme recurs in the line "a man on whom the sun has gone down", a reference to the nekuia from canto I, which is then explicitly referred to.

This recalls The Seafarer , and Pound quotes a line from his translation, "Lordly men are to earth o'ergiven", lamenting the loss of the exiled poet's companions. Another major theme running through this canto is that of the vision of a goddess in the poet's tent. This starts from the identification of a nearby mountain with the Chinese holy mountain Taishan and the naming of the moon as sorella la luna sister moon. The two threads are further linked by the placement of the Greek word brododactylos "rosy-fingered" applied by Homer to the dawn but given here in the dialect of Sappho and used by her in a poem of unrequited love.

These images are often intimately associated with the poet's close observation of the natural world as it imposes itself on the camp; birds, a lizard, clouds, the weather and other images of nature run through the canto. Images of light and brightness associated with these goddesses come to focus in the phrase "all things that are, are lights" quoted from John Scotus Eriugena. He, in turn, brings us back to the Albigensian Crusade and the troubadour world of Bernard de Ventadorn.

Another theme sees Ecbatana , the seven-walled "city of Dioce", blend with the city of Wagadu , from the African tale of Gassire's Lute that Pound derived from Frobenius. This city, four times rebuilt, with its four walls, four gates and four towers at the corners is a symbol for spiritual endurance. It, in turn, blends with the DTC in which the poet is imprisoned.

The question of banking and money also recurs, with an antisemitic passage aimed at the banker Mayer Amschel Rothschild. The canto then moves on to a longish passage of memories of the moribund literary scene Pound encountered in London when he first arrived, with the phrase "beauty is difficult", quoted from Aubrey Beardsley , acting as a refrain. After more memories of America and Venice, the canto ends in a passage that brings together Dante's celestial rose, the rose formed by the effect of a magnet on iron filings, an image from Paul Verlaine of a fountain playing in the moonlight, and a reference to a poem by Ben Jonson in a composite image of hope for "those who have passed over Lethe ".

Compare the nekuia of canto I. There follows a passage in which the poet recognises the Jewish authorship of the prohibition on usury found in Leviticus. Conversations in the camp are then cross-cut into memories of Provence and Venice, details of the American Revolution and further visions. These memories lead to a consideration of what has or may have been destroyed in the war.

Pound remembers the moment in Venice when he decided not to destroy his first book of verse, A Lume Spento , an affirmation of his decision to become a poet and a decision that ultimately led to his incarceration in the DTC. The canto ends with the goddess, in the form of a butterfly, leaving the poet's tent amid further references to Sappho and Homer. The goddess in her various guises appears again, as does Awoi's hennia , the spirit of jealousy from Aoi No Ue , a Noh play translated by Pound.

The canto closes with an invocation of Dionysus Zagreus. After references to politics, economics, and the nobility of the world of the Noh and the ritual dance of the moon-nymph in Hagaromo that dispels mortal doubt, the canto closes with an extended fertility hymn to Dionysus in the guise of his sacred lynx. The canto is concerned with the aftermath of war, drawing on Yeats' experiences after the Irish Civil War as well as the contemporary situation.

Pound writes of the decline of the sense of the spirit in painting from a high-point in Sandro Botticelli to the fleshiness of Rubens and its recovery in the 20th century as evidenced in the works of Marie Laurencin and others. This is set between two further references to Mont Segur. The canto then closes with two passages, one a pastiche of Browning, the other of Edward Fitzgerald 's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam , lamenting the lost London of Pound's youth and an image of nature as designer. The opening line, " Zeus lies in Ceres ' bosom", merges the conception of Demeter, passages in previous cantos on ritual copulation as a means of ensuring fertility, and the direct experience of the sun Zeus still hidden at dawn by two hills resembling breasts in the Pisan landscape.

The canto then moves through memories of Spain, a story told by Basil Bunting, and anecdotes of a number of familiar personages and of George Santayana. At the core of this passage is the line " to break the pentameter, that was the first heave ", Pound's comment on the "revolution of the word" that led to the emergence of Modernist poetry in the early years of the century. The goddess of love then returns after a lyric passage situating Pound's work in the great tradition of English lyric, in the sense of words intended to be sung. This is followed by a passage that draws on Pound's London memories and his reading of the Pocket Book of Verse.

A passage addressed to a Dryad speaks out against the death sentence and cages for wild animals and is followed by lines on equity in government and natural processes based on the writings of Mencius. The tone of placid acceptance is underscored by three Chinese characters that translate as "don't help to grow that which will grow of itself" followed by another appearance of the Greek word for weeping in the context of remembered places.

The canto moves on through a long passage remembering Pound's time as Yeats' secretary in and a shorter meditation on the decline in standards in public life deriving from a remembered visit to the senate in the company of Pound's mother while that house was in session. This letter contained news of the death in the war of J.

Audioboom / Irish Epic Poem in 33 Cantos (/1) - a new reading

Angold , a young English poet whom Pound admired. This news is woven through phrases from a lament by the troubadour Bertran de Born which Pound had once translated as "Planh for the Young English King" and a double occurrence of the Greek word tethneke "died" remembered from the story of the death of Pan in Canto XXIII.

This death, reviving memories of the poet's dead friends from World War I, is followed by a passage on Pound's visit to Washington, D. Much of the rest of the canto is concerned with the economic basis of war and the general lack of interest in this subject on the part of historians and politicians; John Adams is again held up as an ideal. The canto also contains a reproduction, in Italian, of a conversation between the poet and a "swineherd's sister" through the DTC fence. He asks her if the American troops behave well and she replies OK. He then asks how they compare to the Germans and she replies that they are the same.

Pound was flown from Pisa to Washington to face trial on a charge of treason on the 16th of November Found unfit to stand trial because of the state of his mental health, he was incarcerated in St. Elizabeths Hospital , where he was to remain until Here he began to entertain writers and academics with an interest in his work and to write, working on translations of the Confucian Book of Odes and of Sophocles ' play Women of Trachis as well as two new sections of the cantos; the first of these was Rock Drill. In an interview given in , and reprinted by J.

Sullivan see References , Pound said that the title Rock Drill "was intended to imply the necessary resistance in getting a main thesis across — hammering. There are also a small number of Greek words. The overall effect for the English-speaking reader is one of unreadability, and the canto is hard to elucidate unless read alongside a copy of Couvreur's text.

The core meaning is summed up in Pound's footnote to the effect that the History Classic contains the essentials of the Confucian view of good government. In the canto, these are summed up in the line "Our dynasty came in because of a great sensibility", where sensibility translates the key character Ling, and in the reference to the four Tuan, or foundations, benevolence, rectitude, manners and knowledge. Rulers who Pound viewed as embodying some or all of these characteristics are adduced: Roosevelt and Harry Dexter White , who stand for everything Pound opposes in government and finance.

The world of nature, Pound's source of wealth and spiritual nourishment, also features strongly; images of roots, grass and surviving traces of fertility rites in Catholic Italy cluster around the sacred tree Yggdrasil. The natural world and the world of government are related to tekhne or art. Victor , with his emphasis on modes of thinking, makes an appearance, in close company with Eriugena, the philosopher of light. Canto LXXXVI opens with a passage on the Congress of Vienna and continues to hold up examples of good and bad rulers as defined by the poet with Latin and Chinese phrases from Couvreur woven through them.

The word Sagetrieb , meaning something like the transmission of tradition, apparently coined by Pound, is repeated after its first use in the previous canto, underlining Pound's belief that he is transmitting a tradition of political ethics that unites China, Revolutionary America and his own beliefs. Here, he combines Confucianism with Neo-Platonism—Y Yin was a Chinese minister famous for his justice, while Erigena refers to the Irish Neo-Platonist who emphasized regeneration and polytheism.

Canto LXXXVII opens on usury and moves through a number of references to "good" and "bad" leaders and lawgivers interwoven with Neoplatonic philosophers and images of the power of natural process. This culminates in a passage bringing together Laurence Binyon 's dictum slowness is beauty , the San Ku, or three sages, figures from the Chou King who are responsible for the balance between heaven and earth, Jacques de Molay , the golden section , a room in the church of St. Hilaire , Poitiers built to that rule where one can stand without throwing a shadow, Mencius on natural phenomena, the 17th-century English mystic John Heydon who Pound remembered from his days working with Yeats and other images relating to the worship of light including "'MontSegur, sacred to Helios ".

The canto then closes with more on economics. Pound viewed the setting up of this bank as a selling out of the principles of economic equity on which the U. At the centre of the canto there is a passage on monopolies that draws on the lives and writings of Thales of Miletus , the emperor Antoninus Pius and St. Ambrose , amongst others. The same examples of good rule are drawn on, with the addition of the Emperor Aurelian. Possibly in defence of his focus on so much "unpoetical" material, Pound quotes Rodolphus Agricola to the effect that one writes "to move, to teach or to delight" ut moveat, ut doceat, ut delectet , with the implication that the present cantos are designed to teach.

The naturalists Alexander von Humboldt and Louis Agassiz are mentioned in passing. Apart from a passing reference to Randolph of Roanoke, Canto XC moves to the world of myth and love, both divine and sexual. The canto opens with an epigraph in Latin to the effect that while the human spirit is not love, it delights in the love that proceeds from it. The Latin is paraphrased in English as the final lines of the canto.

Following a reference to signatures in nature and Yggdrasil, the poet introduces Baucis and Philemon , an aged couple who, in a story from Ovid 's Metamorphoses , offer hospitality to the gods in their humble house and are rewarded. In this context, they may be intended to represent the poet and his wife.

This canto then moves to the fountain of Castalia on Parnassus. This fountain was sacred to the Muses and its water was said to inspire poetry in those who drank it. The next line, "Templum aedificans not yet marble", refers to a period when the gods were worshiped in natural settings prior to the rigid codification of religion as represented by the erection of marble temples. The "fount in the hills fold" and the erect temple Templum aedificans also serve as images of sexual love. Then the goddess appears in a number of guises: In a litany, she is thanked for raising Pound up m'elevasti , a reference to Dante's praise of his beloved Beatrice in the Paradiso out of hell Erebus.

The canto closes with a number of instances of sexual love between gods and humans set in a paradisiacal vision of the natural world. The invocation of the goddess and the vision of paradise are sandwiched between two citations of Richard of St. Victor's statement ubi amor, ibi oculus est "where love is, there the eye is" , binding together the concepts of love, light and vision in a single image.

The crystal image, which is to remain important until the end of The Cantos , is a composite of frozen light, the emphasis on inorganic form found in the writings of the mystic Heydon, the air in Dante's Paradiso , and the mirror of crystal in the Chou King amongst other sources. These couples can be seen as variants on Ra-Set. Much of the rest of the canto consists of references to mystic doctrines of light, vision and intellection.

There is an extract from a hymn to Diana from Layamon 's 12th-century poem Brut. An italicised section, claiming that the foundation of the Federal Reserve Bank , which took power over interest rates away from Congress, and the teaching of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud in American universities "beaneries" are examples of what Julien Benda termed La trahison des clercs , contains antisemitic language. Towards the close of the canto, the reader is returned to the world of Odysseus; a line from Book Five of the Odyssey tells of the winds breaking up the hero's boat and is followed shortly by Leucothea , "Kadamon thugater" or Cadmon's daughter offering him her veil to carry him to shore "my bikini is worth yr raft".