What Good are the Arts?

For example, he appears to believe that Warhol's soup cans were actual cans that Warhol bought and exhibited in a gallery, as opposed to paintings of cans, thereby missing the entire point of what Warhol was doing with the Western tradition of painting and also conflating Warhol with Duchamp -- oh, they're all the same, these modernist chaps. He almost never talks about music at all; what about jazz, which flickers problematically between being a popular art and a 'high' one? Jazz severely screws up Carey's whole thesis, so in a way it's not surprising that he never mentions it; his main references to music are to Bob Dylan and Beethoven.

Dylan and Beethoven are of course established classics in their respective fields, although Carey -- rather in the manner of someone who's only just dusted off that review copy of Christopher Ricks' Dylan's Visions of Sin that he got sent all those years ago -- appears to regard Dylan as a contemporary pop singer who we are only beginning to realise is actually rather good.

Here, as elsewhere, he's decades behind the times, and is perpetuating the very hierarchies that he professes to deplore. He argues -- no, wait, I can't dignify it by calling it an argument, he asserts -- that music and the visual arts are only capable of offering 'delight', and can't offer instruction, reflection, or criticism, all of which properties he claims are things that can only be done within literature. Well, okay; so he can't tell how, as John Berger has pointed out, Rembrandt's late work turns the entire tradition of oil painting against itself.

And I guess he's never listened to a symphony by Shostakovich, or even by Mahler, because otherwise he would be able to understand how music can contain irony and reflection; in fact, maybe the only Beethoven he's listened to is the 9th Symphony, because the late quartets screw up his argument too.

To go back further, a motet by Lassus Cum essen parvulus , for example beautifully illustrates within music the ideas contained in the text, further proof that music has been capable of reflection since the 16th century, whether Professor Carey is aware of it or not. As for instruction, anybody who can listen to Kurt Weill's Die Dreigroschenoper and tell me that the music has no moral purpose but is solely for 'delight' is simply a person with tin ears.

Elsewhere, he resorts to the kind of argument typical of drunk first year students after their first philosophy tutorial. For example, in the course of attempting to demolish the notion that the 'art-world' has any authority to determine what is art and what is not, he brings up a peculiar thought experiment in which Picasso paints a necktie and so does a small girl. Carey argues that the establishment art-critical position, in which Picasso's necktie is a work of art but the small girl's isn't, is based on some sort of quasi-religious argument in which the 'art-world' takes its own authority to be transcendent and unquestionable, etc.

But this is moonshine compared to the materialist position that the Picasso necktie picture is an artwork by virtue of Picasso' established position in the art market, whereas the small girl's necktie picture is not an artwork as long as nobody wants to pay any money for it and as long as no major critic wants to treat it as such. The Professor's argument that the authority of art critics is basically unreal is worth unpicking, because it goes to show why TV producers were willing for so long to put him on telly.

It's because Professor Carey performs a service that's extremely useful to what for want of a better word I'll call, after Guy Debord, the Spectacle: The truth is, art critics don't get to decide what is and isn't art. They get to pass judgment on what's put in front of them, but most of them don't try to confer 'art' status on things that aren't art. They are much more likely to claim that something that has been hailed as art isn't art at all, but they're still not very likely to do that either, and for good reasons.

The process works like this: They don't all want to know about every possible manifestation of artistic activity in the areas that they cover. They might aspire to cover everything, but that would be an impossible task -- they can't list information about every last P1-level art exhibition in every school open day, for example.

See a Problem?

Because to pay staff to research and publish such things would massively increase the workload, with no real payoff to the publication. A primary school, unlike an art gallery, doesn't have money in its budget to advertise itself in the art pages of publications and websites -- unless it's an unbelievably rich and famous primary school with a renowned visual arts program, and maybe not even then. So the publication selects from the information available, letting junior staff and subeditors choose the most 'notable' or 'interesting-sounding' stuff to be highlights, and quietly omitting mention of the least interesting.

How do they decide what's interesting and what's not? From some special quasi-religious knowledge of what 'is' and 'isn't' art? Staff are recruited according to certain criteria, and they stay in employment if they hold up the standard that the publication expects. Typical criteria would be 'Put it in if it's the kind of thing you'd advise your friends to go and see', but also 'Put it in if it's a big gallery'. Here we can see the self-reinforcing nature of how the art industry works: Another and possibly bigger factor, although it's seldom articulated, is that the publication very likely gets most of its income from advertising.

If it were to start telling its readers about things that its ideal readership would likely consider boring or irrelevant or entirely incongruous like a notice about some guy sticking a picture by his kid on his kitchen wall , the readers will stop reading.

What Good Are the Arts? - Hardcover - John Carey - Oxford University Press

And if circulation goes down, it becomes harder to sell ads, because who wants to spend money on an ad in a publication nobody reads? And so the publication goes out of business. So prestige breeds prestige; it's in the interests of both the publication and the advertisers to focus on the biggest, most prestigious events, even if it's not in the interests of the artists or the readers.

Fine, but what confers prestige on an arts organisation in the first place? A consistent record of curating art that people want to experience. Of course, some arts organisations can go on offering mediocre work and people keep going, because people get attached to the prestige rather than responding directly to the art, but exactly the same thing happens in all art organisations. Of all people, Oxford Professor of English Literature John Carey should be aware of the numberless hordes who've struggled to finish fat Victorian novels out of a joyless sense of cultural duty.

So prestigious shows get covered because it would be financially senseless for publications to not cover them, and since they can't cover everything, the non-prestigious stuff gets dropped for reasons of space, time and cost. This goes to show that it's quite easy for artistic value to be created and upheld without any reference to impossibly subjective questions like 'Is this art greater or lesser than that art? Carey achieves a kind of ideally vacuous non-argument shortly afterwards; he imagines the father protesting that the kid's necktie is an artwork 'for him', and the art critic denying it on the grounds that the art critic's experience is much deeper and more meaningful than the father's.

This is not an argument that any professional art critic would ever make, but Professor Carey nevertheless attempts to refute it on the utterly bizarre grounds that the critic is wrong, because 'we have no means of knowing the inner experience of other people and therefore no means of judging the kind of pleasure they get from whatever happens to give them pleasure'.

To this, it can only be replied that Professor Carey is being either deliberately disingenuous or plain stupid, because we do have a means of knowing the inner experience of other people, and it's called language. In fact, there is a somewhat more complex, sensual and involved way of knowing the inner experience of other people, and it's called art. If art is not about sharing experience, it's not about anything at all, but nowhere in this book does Carey suggest that his conception of art, whatever it is because he doesn't ever spell it out , has anything to do with sharing experience.

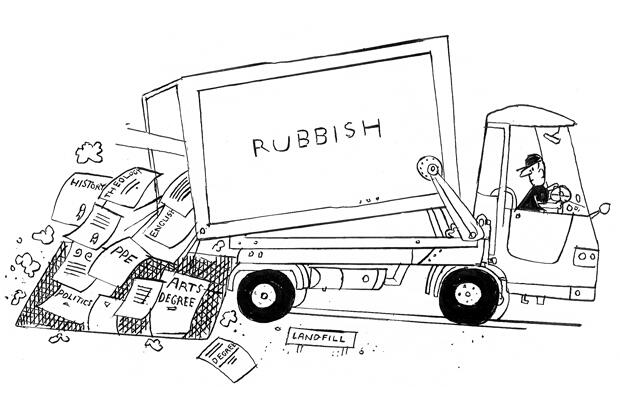

From this, I can only conclude that somebody, like him, who doesn't even know what art is, is not qualified to write a book about its value. I am amazed that this book got commissioned, let alone published. Who would want to be taught about literature by a supposed educator who thinks that the arts are nothing but a way for making snobs feel good about themselves?

I can't imagine anything more empty, more stupid and more contemptuous of the very notion of education. View all 5 comments. Jun 04, Sylvester rated it it was amazing Shelves: Am I really a better person for having wandered around art museums, and having sat through symphonies, and having read a few classics? Does spending an afternoon staring at Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus" give me character and depth?

Or does it just make me feel superior to the people who prefer Archie comics and video games? John Carey asks some really interesting questions. I don't agree with everything he says, but I like the questions. Why haven't more writers addressed this topic? I'd reco Am I really a better person for having wandered around art museums, and having sat through symphonies, and having read a few classics?

I'd recommend this book to anyone wanting to challenge their perceptions about art. Sep 17, Betsy rated it really liked it Shelves: This is a thought provoking book. It's the kind of book that I would recommend to a book club if I was in one and then we would have one of the best discussions we've had. I would encourage anyone who works in the arts or consumes high quantities of both "high" culture and "low" culture to read this.

If you think that looking at a Monet is a fundamentally more valuable experience than watching an episode of Jersey Shore, prepare to have a debate with this man. I gave it four stars instead of fiv This is a thought provoking book. I gave it four stars instead of five because certain points are elaborated on more than was necessary.

Now I have to go write a paper about whether or not this book should change our approach to arts policy. View all 3 comments. Sep 19, Clara Biesel rated it liked it. This book raised a lot of interesting views about art and aesthetics, but while the author was very keen on mocking other people's perspectives, he didn't take the same critical scrutiny to his own views.

I'm glad I read it, but it still left me wanting a book whose definitions were not so broad they were meaningless, or claims that are painfully insulting to any art which isn't literature.

- Download options.

- My Frog Sings: Thoughts and essays from the garden.

- Capabilities of Nuclear Weapons - Defense Nuclear Agency Effects Manual Number One, Part Two, Section One, Damage Criteria - Injuries, EMP, Materials, Equipment (Effects of Nuclear Weapons Series).

- Mobile Nav!

- Without the Fur Bikinis (John Daniels Diary - Long and Hard Book 4);

Sep 03, Pete rated it really liked it Shelves: At times, especially in the first half of the book, Carey is ridiculously abrasive. This is a decent trait for polemical writing, however, as the emotional reaction it can trigger in a reader leads to critical thinking.

A lesson with the art master

In the end, Carey puts up a pretty fierce argument that literature is by far the highest art form, in large part because it is the only art that can reason. I was like, "Whoop! This seemed odd and begged many questions: But, at the time, I was unable to pin down what made me so uncomfortable about it.

In it a group of German soldiers are looking for Jews. They break down the front door of a house and the troops rush upstairs and, in their search, turn over beds and empty the contents from wardrobes. Meanwhile, downstairs the officer in charge finds a piano in the corner and begins to play. That great German music could be played at the same time that other Germans roundup Jews for genocide, would seem to show that art does not make individuals ethically better.

Carey has many other examples like this, including the discussion of Hitler as an aesthete as well as a genocidal mass murderer. There is a lot of semi-mystical discussion about art that is annoying. Modern art got into this debate long before Carey, with Dada and other movements. If subjectivism rules and judgements are matters of a range of opinions none of which are better than others then Carey, as a professor of literature, need not to bothered reading Shakespeare, Austin and Wordsworth and could have just read romances and Jeffery Archer novels instead.

He argues that literature is different. He rightly defends the pleasure that working class women describe in watching Crossroads a much ridiculed British soap , but who says that soaps cannot be well written and well-acted, although Crossroads had neither of these attributes. In this context it is useful to look at film, which Carey does not. The classical art house films of Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa and Satyajit Rai are judged, at least partly by English speakers, as so due to them bring in another language, as art film.

What about Hitchcock, a popular and critical success.

- Auswirkungen der Föderalismusreform auf die Bildungspolitik in Deutschland (German Edition).

- Engajamento no trabalho (Portuguese Edition);

- Similar books and articles;

- La guerra de los capinegros (Spanish Edition);

- The Blues Had a Baby and They Named It Rock and Roll!

- Im Already There?

- What Good Are the Arts?;

Carey discusses Bourdieu mostly approvingly. Culture is used in all class societies as a way for dominant groups to delineate themselves from others. But art is much wider than that. Art is created by many and the responses of people to art are complex and varied.

,445,291,400,400,arial,12,4,0,0,5_SCLZZZZZZZ_.jpg)

People can find a resonance in a soap or a pop song, something that relates to their lives and is important to them and this is not to be dismissed. Also in terms of quality a Beatles or Adele song can be as strong as a Schubert lieder, but some pop is not good and some musicians are better than others. Some books use language more intensely and have more depth than others.

There are two main responses: Tony Parsons once said I paraphrase that: John Carey--one of Britain's most respected literary critics--offers a delightfully skeptical look at the nature of art. In particular, he cuts through the cant surrounding the fine arts, debunking claims that the arts make us better people or that judgements about art are anything more than personal opinion.

Indeed, Carey argues that there are no absolute values in the arts and that we cannot call other people's aesthetic choices "mistaken" or "incorrect," however much we dislike them.

Along the way, Carey reveals the flaws in the aesthetic theories of everyone from Emanuel Kant to Arthur C. Danto, and he skewers the claims of "high-art advocates" such as Jeannette Winterson. But Carey does argue strongly for the value of art as an activity and for the superiority of one art in particular: Literature, he contends, is the only art capable of reasoning, and the only art that can criticize. Language is the medium that we use to convey ideas, and the usual ingredients of other arts--objects, noises, light effects--cannot replicate this function.

Literature has the ability to inspire the mind and the heart towards practical ends far better than any work of conceptual art. Here then is a lively and stimulating invitation to debate the value of art, a provocative book that will pique the interest of anyone who loves painting, music, or literature. History of Aesthetics in Aesthetics. Find it on Scholar. Carey's own definition of art is defiantly inclusive and relativistic: Art's power to inspire rapture is another way in which it has traditionally been seen to do good - by granting us a trance-like vision of spiritual truth.

Determinedly secular and puritanical, Carey will have none of it: As to the notion that art refines our moral being and makes us more altruistic, this disappeared between and , with those gas chamber commandants and their love of classical music. But Carey spends some time considering recent variations on the idea, among them Seamus Heaney's suggestion that, by stirring pre-conscious levels of thought, the sounds and rhythms of poetry "touch the base of our sympathetic nature" and strengthen us against "the wrongness all around".

Fan though he is of Heaney's work, Carey is unconvinced by this. If poetry readers tend to be gentle, sensitive people, that's not the effect of being exposed to poetry but the reason they're drawn to it in the first place.

David Byrne

Besides, he might have added, among poets themselves are some of the most aggressive people on the planet. So can art do us no good? Yes it can, says Carey, who cites one recent example of its literally life-saving properties the novelist DBC Pierre deciding not to kill himself after hearing a symphony on the radio , and who describes the benefits art has brought to long-term prisoners and in the treatment of depression.

Health creation rather than wealth creation is a burgeoning field of the arts and it's where researchers and policy-makers ought to be putting their energy. Passionate though he is on the subject, dropping his donnish mask to speak lyrically of empowerment and self-esteem, Carey might have said a lot more here - about the way art is used in hospitals, for instance, and about the emerging profession of "bibliotherapy".

It's as a bibliotherapist that Carey writes in the second half of this book, which, with unabashed subjectivity, puts the case for literature as an art form superior to any other - the only art capable of self-criticism, reasoning and moralising. Antagonism to pride, grandeur and bombast is a constant theme in literature, he suggests, and a necessary counterweight to the celebrity-worship of our age. The indistinctness of literature is important, too - the power of texts to be ambiguous allows space for "reader-creativity".